American Bison

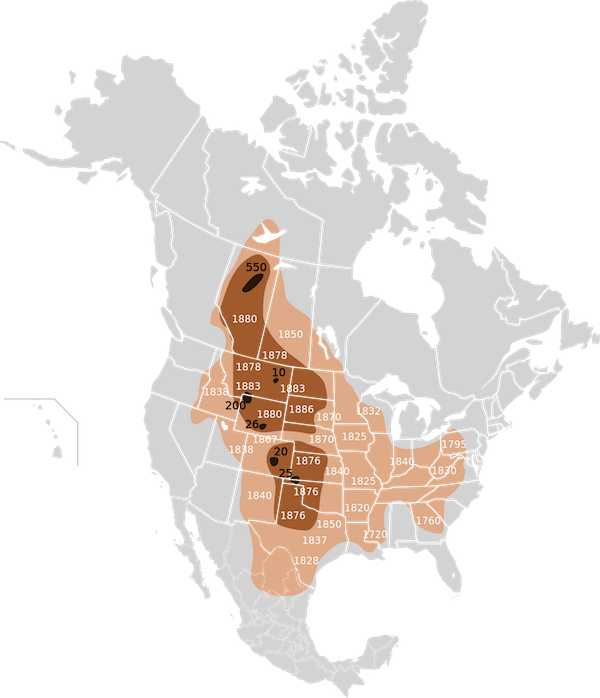

The American bison is often cited as one of the success stories of species rescue and conservation. In the late nineteenth century they teetered on the brink of extinction, as a result of both the transformation of the open range to suit the needs of such enterprises as railroads and ranches, and officially sponsored extermination campaigns to undermine the livelihood of Plains Indians. Unlike the quagga, whose vulnerability was recognized during the same period, the bison benefited from intervention that was sufficiently timely to be effective. A remnant population was protected when Yellowstone National Park was established in 1872, and small groups also survived elsewhere in the United States and Canada. Although their populations remain far below their historical maximum (in the tens of thousands compared to estimates as high as 50 million or more), and the Red List of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature classifies them as Near Threatened, bison are now sufficiently numerous to be eaten undiluted as buffaloburgers or in hybridized form as beefalo. In 2016 Barack Obama signed a law making the bison the national mammal of the United States (the bald eagle, recently recovered from its own brush with extinction, remains the national animal).

The American bison is often cited as one of the success stories of species rescue and conservation. In the late nineteenth century they teetered on the brink of extinction, as a result of both the transformation of the open range to suit the needs of such enterprises as railroads and ranches, and officially sponsored extermination campaigns to undermine the livelihood of Plains Indians. Unlike the quagga, whose vulnerability was recognized during the same period, the bison benefited from intervention that was sufficiently timely to be effective. A remnant population was protected when Yellowstone National Park was established in 1872, and small groups also survived elsewhere in the United States and Canada. Although their populations remain far below their historical maximum (in the tens of thousands compared to estimates as high as 50 million or more), and the Red List of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature classifies them as Near Threatened, bison are now sufficiently numerous to be eaten undiluted as buffaloburgers or in hybridized form as beefalo. In 2016 Barack Obama signed a law making the bison the national mammal of the United States (the bald eagle, recently recovered from its own brush with extinction, remains the national animal).

The relation of contemporary bison to the noble former inhabitants of the Great Plains is far from straightforward. The bison who end up in fast food restaurants and grocery stores clearly come from domesticated stock, not from the wild herds that roam Yellowstone National Park and similar preserves; and the name “beefalo” indicates the mixed descent of those animals from both the American bison (Bison bison) and the domestic cow (Bos taurus). But it also appears that that beneath their reassuring demographic success, even the apparently wild bison populations may be similarly compromised. They look like bison and they act like bison; they seem indistinguishable from the iconic beast who once adorned the American nickel. Recently developed techniques of genetic analysis have suggested that looks can be deceptive; a 2013 article in Sierra magazine pointedly celebrated the 3,700 Yellowstone bison as "free of cattle genes...our last wild bison." Despite their reassuring phenotype, most of the current American bison (in public herds as well as in private herds) include substantial genetic contributions from domesticated cattle. At least in theory (and if it is assumed that genotype trumps phenotype), this raises substantial questions about exactly what has been saved and why.

The relation of contemporary bison to the noble former inhabitants of the Great Plains is far from straightforward. The bison who end up in fast food restaurants and grocery stores clearly come from domesticated stock, not from the wild herds that roam Yellowstone National Park and similar preserves; and the name “beefalo” indicates the mixed descent of those animals from both the American bison (Bison bison) and the domestic cow (Bos taurus). But it also appears that that beneath their reassuring demographic success, even the apparently wild bison populations may be similarly compromised. They look like bison and they act like bison; they seem indistinguishable from the iconic beast who once adorned the American nickel. Recently developed techniques of genetic analysis have suggested that looks can be deceptive; a 2013 article in Sierra magazine pointedly celebrated the 3,700 Yellowstone bison as "free of cattle genes...our last wild bison." Despite their reassuring phenotype, most of the current American bison (in public herds as well as in private herds) include substantial genetic contributions from domesticated cattle. At least in theory (and if it is assumed that genotype trumps phenotype), this raises substantial questions about exactly what has been saved and why.

| « Quagga | Dodo » |