Tropical Storm Allison (2001)

The history of Houston is elemental. The air of the city is relentlessly hot and humid. When urban planners call Houston the “unplanned city,” they say it is because of the commitment to home ownership. The saying goes that Houstonians want to “own the dirt” – the thick clay, and not very absorbent, “black gumbo” soil of the city. Also elemental, the city refines 2.6 million barrels of crude oil per day, which is ultimately responsible for the emission of so much CO2 into the air.

Then, there is water. Houston first came into existence during the 1830s, a real estate speculation, due its proximity to a naturally protected port, with an extensive system of bayous that crossed with, from the east, the encroaching cotton frontier of the antebellum southern slave economy. Later, in the early twentieth century, after the 1901 discovery of the Spindletop oil field 87 miles east in Beaumont, Texas, the federal government dredged the Buffalo Bayou into the Houston Ship Channel, and the modern city was born.

As for water, the city floods, a lot – and not just recently, always. The city’s first devastating flood came in 1935. The photographs look eerily familiar today.

|

|

|

Every summer, tropical storms bring sheets of rain. The water pools in the streets, and the anxious waiting begins. How far up the front lawns will the water climb? Will it pour into the house?

In June 2001, I was living in Houston, fresh out of college, working for the Congresswoman who represented the downtown area, and a number of adjacent, largely African-American and poor neighborhoods. Only days on the job, Tropical Storm Allison hit, dumping as much as 40 inches of rain on parts of the city.

The statistical analyses of recent scientific studies, many published since Hurricane Harvey (2017), estimate that storms like Allison are in the range of 1.5 to 5 times more likely due to human-induced climate change, as warmer ocean water means more evaporation and more water vapor in the air for storms to gather and expel. The heat that rises from asphalt and concrete does not help. A recent article in Nature suggests that the wind drag of atmospheric friction due to urban development may slow storms down. Allison lingered on top of Houston for nearly a week.

When Allison struck, I was housesitting for family friends in one of the city’s southwest neighborhoods, near Brays Bayou. The second evening of the storm the water began to rise, above the sidewalk. I nervously fretted over our friends’ home and their possessions at night, while during the day I huddled with officials from George W. Bush’s Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA).

|

|

|

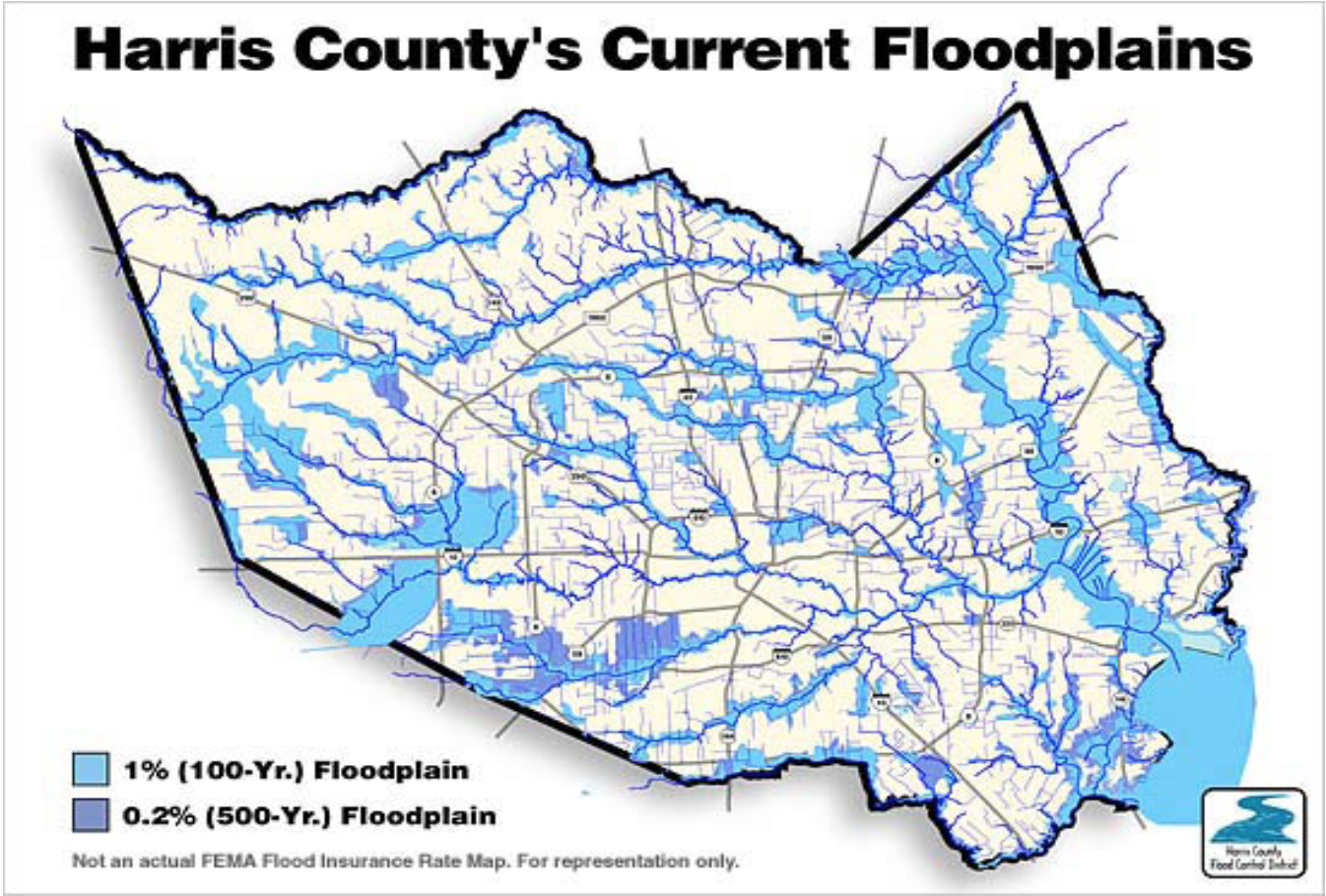

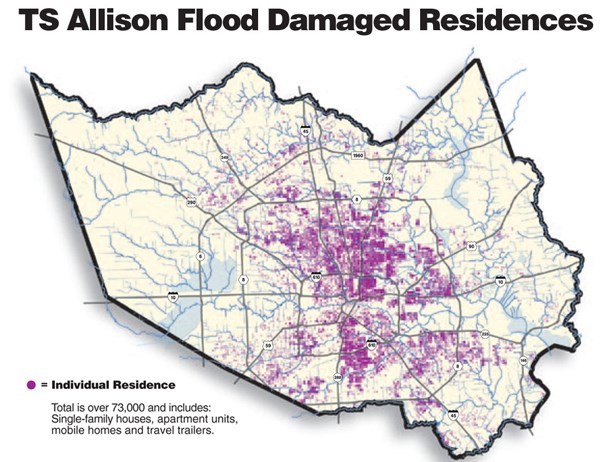

What was striking was how much of the post-flood effort was geared toward compensation for property loss. The county branded Allison the “worst rainstorm to ever befall an American city in modern history,” because it led to more than $5 billion of property loss, the most ever. But it was all mostly a matter of insurable risk, as FEMA’s greatest interest, seemingly, was the 100-year and 500-year floodplain maps, which the agency used for purposes of selling and subsidizing flood insurance and re-insurance. I remember a meeting I attended, chaired by FEMA director Joe Allbaugh, which included officials from both the Harris County Flood Control District and the city. Allbaugh, recently Bush’s Texas gubernatorial campaign director, would soon leave FEMA and found a consulting firm that, according to its website, helped clients “take advantage of business opportunities in the Middle East following the conclusion of the US-led war in Iraq.” He had little to say. The county official, his office responsible for drawing the maps, was nearly grief stricken, as the 100-year and the 500-year floodplain maps had predicted only about half of where the flooding had occurred. They would have to be redrawn. Because of this storm and others, in the past four decades Houston has seen the worst “urban flooding” in the US, defined as flooding outside a 100 or even 500-year flood plain. The maps are not worth that much. In 2001, over night the floodplain expanded by 20 percent.

That same county official rolled out a map of the city, and, pointing his finger at certain points along the bayous, said, “Of course, no one should rebuild here, here, and here.” After Allison, the city tried to pass a law banning major renovations or new developments on “floodways,” the most vulnerable points on the 100-year floodplain. Multiple lawsuits followed, claiming violations of property rights. Two years later, the City Council backed down. Homeowners owned the dirt. In George W. Bush’s proclaimed “ownership society” of the 2000s, with cheap mortgage financing and subsidized FEMA flood insurance available, there was a right to rebuild.

When Hurricane Harvey (2017), another slow, lingering rainstorm – in many parts of the city a 10,000-year storm, and the third 500-year storm since 2015 – dropped about nine trillion gallons of water on Houston, I wondered how many of the destroyed homes had been pointed out by that county official sixteen years earlier. More than a few, I would guess. But it would have meant little to tell those residents they could not rebuild, and to have left it that. A far more grand initiative would have been required to tackle the real problem.

Houston consists of three distinct infrastructural “systems.” They conflict. The first is ecological, and consists of a banded network of bayous, into which thousands of channels and gullies empty. The bayous flow eastward, toward the main Buffalo Bayou and on to the San Jacinto River, which empties south into the Gulf of Mexico.

In the postwar period, federally funded civil engineers bulldozed, graded, and poured concrete over the walls of the bayous, as if they were water freeways, transforming them into effectively open storm sewers.

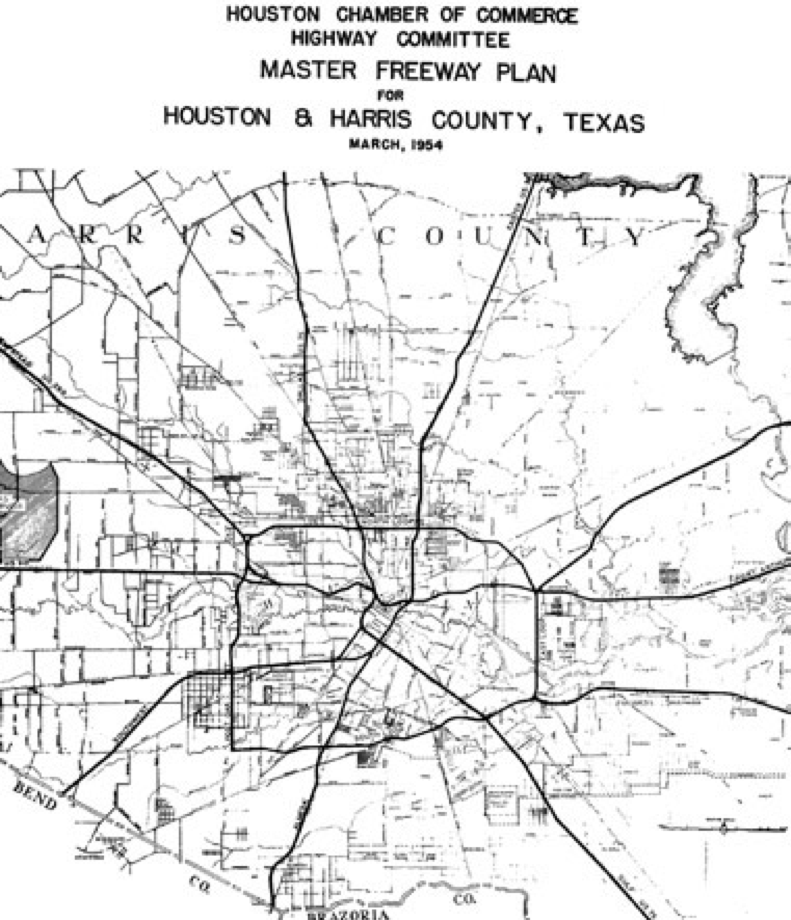

Second, there is the freeway system. Modern in design, it ignores the water-based organization of the bayous. It is a concentric hub-and-spoke arrangement, oriented around the city’s downtown.

|

|

Finally, there is the third, urban system, which follows yet another pattern. It is polycentric, hardly oriented toward a central downtown.

Large areas of development, such as the southwestern neighborhood I grew up in, Meyerland, arose along the freeways. The places where freeways (and thus population density) and bayous cross are the most vulnerable to flooding. Meyerland, which Brays Bayou runs through, is one of them. The densest of these junctures were the dots on the 100-year flood plain map pointed out by the county flood district official back in 2001. But for dots like this not to exist, the city’s infrastructure would have to be completely redone in order to accommodate rather than to attempt to overcome the unbending logic of the ecosystem. Looking at the maps, this is obvious.

If it was a mistake, born of typical high modernist hubris, to ignore the flow of the bayous when building the city, it is also true that city’s now entrenched hub-and-spoke freeway system represented a typical mid-twentieth century effort by liberals to “plan” the city’s future development – a plan that proved useless, if not in the end counterproductive. The amplification of these mistakes by a postmodern pattern of urban sprawl that follows a more market-based logic of its own – and every time a developer pours concrete it reduces the amount of water the ground can absorb, while the floodplain imperceptibly shifts – explains much of the city’s vulnerability to floods.

But so do the property interests of homeowners. After Allison, not only did property owners block floodway building restrictions in the courts, they also filed suits preventing a city property tax to pay for drainage improvements. There was a modest government $15 million program to buy out homes in floodways, but only 2,400 property owners voluntarily sold. After Harvey, on the one-year anniversary of the storm in 2018, voters approved a $2.5 billion bond issue to finance various flood control projects. A law passed City Council 9-7 mandating that rebuilding in the floodplains would have to take place 2 feet above base elevation. Still, many Houston homeowners in the worst parts of the floodplain have opted to remain, elevating their homes at great cost. And, there have been more post-Harvey lawsuits filed by property owners, most prominently a suit on behalf of homeowners flooded when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers chose to release water from the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs on the northwest side of town, first built after the 1935 storm. The release prevented an estimated $60 billion of damage, should the reservoirs have been breached. Homeowners maintain the act violated the “takings clause” of the US Constitution’s 5th Amendment.

Meyerland, first developed during the 1950s for whites, many of them Jewish, and many in flight from black population growth in the Third Ward, is a 9-square mile subdivision almost completely inside the 100-year floodplain. It was utterly devastated by the 2015-2017 flood cycle.

Of the 2,309 total “homesites” in Meyerland, 914 flooded during Harvey. But 728 of these flooded for second or third time in 2017 since 2015. A January 2017 Houston Chronicle article, before Harvey, referred to a Meyerland therapist who had initiated “a group for owners of flooded homes.” “I had a couple people say they were so depressed, they wanted to commit suicide. They saw no end.” Even after Harvey, when under the weight of floodwaters the city sank a half an inch, the neighborhood has slowly been rebuilt again – and elevated.  One Houston homeowner paid a contractor $300,000 to raise his home a full six feet, explaining to the Texas Tribune that, “Everything is great except the flooding. Here, we know our neighbors, we love our schools, it’s close to work. We didn’t want to leave.” Surely, the water could never go six-feet high?

One Houston homeowner paid a contractor $300,000 to raise his home a full six feet, explaining to the Texas Tribune that, “Everything is great except the flooding. Here, we know our neighbors, we love our schools, it’s close to work. We didn’t want to leave.” Surely, the water could never go six-feet high?

Regardless, if someone wanted to raise their home sixty feet, should not they have the right? They own the dirt.

Water, earth, and air, but in the end the most elemental form of the city may be private property.

| « Introduction | Zoning Referendum III » |