Introduction

With climate change, a pressing issue concerns scale. Of course, there is the vast scale of the problem. Scale however is also an issue in a related but different sense – not in terms of gravity, but rather perspective. What is the right scale, from the planetary to the personal, from the political to the ethical, with which to grapple with the problem? For historians, scale is a prerequisite of story telling. Nothing can be about everything all at once. In these essays for the Center for History and Economics on the general theme of “climate change and loss,” I want to focus upon one city, Houston, Texas.

For the contemporary global carbon economy, there is no more important city, arguably, than Houston. Having written a bit about the rise of the city from the 1970s through the early 2000s in my forthcoming book Ages of American Capitalism I know this historical fact well. But I also know it differently, having lived in the city across this same time period.

Or do I? Since the 1970s, Houston, the newest of America’s great cities, has been as it continues to be the fastest growing US city by most every measure – population, territory, new housing starts. My parents, both born and raised in the Midwest (my mother in Ontario), moved there in 1972, the year the Apollo 17 spacecraft, based at Houston’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), snapped the photograph Blue Marble, an important episode in the history of planetary consciousness and scale.

Or do I? Since the 1970s, Houston, the newest of America’s great cities, has been as it continues to be the fastest growing US city by most every measure – population, territory, new housing starts. My parents, both born and raised in the Midwest (my mother in Ontario), moved there in 1972, the year the Apollo 17 spacecraft, based at Houston’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), snapped the photograph Blue Marble, an important episode in the history of planetary consciousness and scale.

I was born in 1978. So I grew up in the city, but also with it. It is remarkable that during the same era that witnessed the scientific confirmation of anthropogenic climate change, and the first political efforts to mitigate it, the most economically dynamic American city was Houston – a city premised upon oil, a city so sprawling it is utterly dependent upon the automobile. Not only is Houston the newest American city, it is also the most dispersed, with a per capita energy consumption twice that of the average European or Japanese city, and with, legend at least has it, thirty parking spaces in the city for every one person. The growth of Houston thus represents both the cause and consequence of a way of life that is now fated to warm the planet. The growth first happened, and kept on happening, exactly as the possibility of that fate became known.

I was raised in Houston during this time, but can I say in any meaningful sense that I saw it happen, watched it unfold? That is a lot to have asked of a child. My parents did not work in the oil industry. Throughout my childhood, my main focus was on playing baseball. Climate change does not come up at all in the television series Friday Night Lights (2006-2011), an accurate enough depiction of my scene. But I was aware early on of the vast scale of Houston – 650 square miles, capable of encompassing Chicago, Baltimore, Detroit, and Philadelphia, or, if you prefer, Chicago, Manhattan, Washington, DC, Boston, San Francisco, and Santa Barbara, all while contained in Harris County, the approximate size of Delaware, in a multi-county metropolitan area larger than the state of New Jersey.

I was raised in Houston during this time, but can I say in any meaningful sense that I saw it happen, watched it unfold? That is a lot to have asked of a child. My parents did not work in the oil industry. Throughout my childhood, my main focus was on playing baseball. Climate change does not come up at all in the television series Friday Night Lights (2006-2011), an accurate enough depiction of my scene. But I was aware early on of the vast scale of Houston – 650 square miles, capable of encompassing Chicago, Baltimore, Detroit, and Philadelphia, or, if you prefer, Chicago, Manhattan, Washington, DC, Boston, San Francisco, and Santa Barbara, all while contained in Harris County, the approximate size of Delaware, in a multi-county metropolitan area larger than the state of New Jersey.

I did have some sense of the city’s relationship to the environment. I can still see from my parents’ car window the approach of the refineries along the Houston Ship Channel on the east side of town. It is the largest refining complex in the US, representing 14 percent of national capacity.

|

|

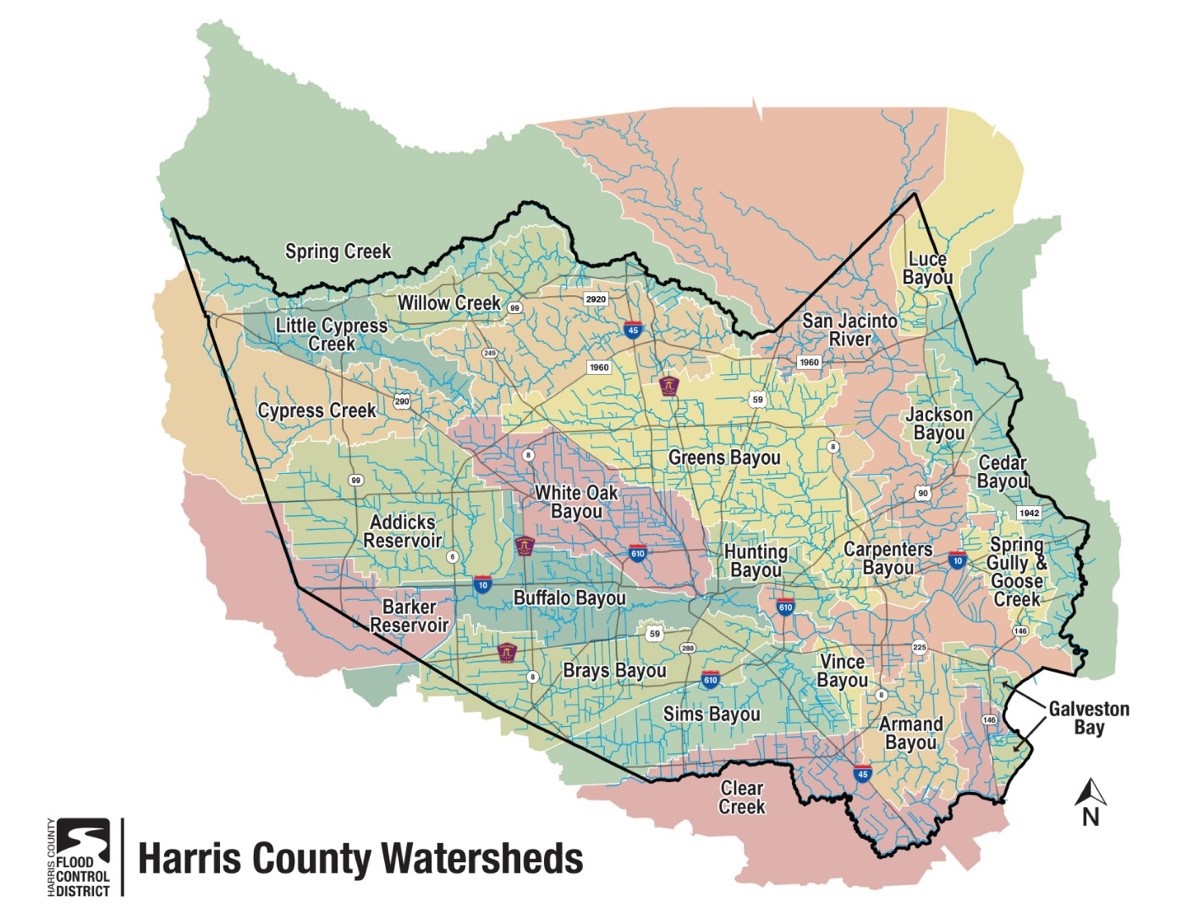

I knew that city residents considered life impossible without the “climate control” of air conditioning. It was obvious that the city was built on wetlands. Of the 2,500 miles of channels that drain Houston when it rains, not far from our house was one of the city’s many bayous, Brays Bayou, which flows into the main conduit, Buffalo Bayou. Since 50 years ago, Buffalo Bayou’s peak flows have increased by 250 percent. In a bad storm, Brays Bayou would always flood.

I knew that city residents considered life impossible without the “climate control” of air conditioning. It was obvious that the city was built on wetlands. Of the 2,500 miles of channels that drain Houston when it rains, not far from our house was one of the city’s many bayous, Brays Bayou, which flows into the main conduit, Buffalo Bayou. Since 50 years ago, Buffalo Bayou’s peak flows have increased by 250 percent. In a bad storm, Brays Bayou would always flood.

Later, after college, my first job, working for a local Congresswoman, was to deal with the aftermath of Tropical Storm Allison (2001). My second job, as a paralegal, dealt with the aftermath of Enron’s infamous manipulation of the California energy market.

Climate change was nowhere in my consciousness. But I now realize that, however indirectly, it was everywhere around me.

There was an era of global warming, now passed, which dates roughly from the 1980s through the early twenty first century. This was the period of attempted scientific communication to the public, of alarm raising and the birth of social movements, and of political efforts to prevent future climate change through international treaty-making. This era is now being joined, perhaps even superseded, by a new one, in which living with climate change, as much as successful or failed prevention and mitigation, also figures. How people have lived with climate change, even if they did not know they were doing it, is the historical question I want to pose to the city of Houston.

As I set out to write these essays, it is not clear to me how the planetary history of climate change and my years in Houston, along with much of what we know has happened to societies since the 1970s, the period of Houston’s prodigious growth, whether it is the rise of a postindustrial service economy, the persistence of an auto-industrial society, the afterlife of Jim Crow liberalism, the ascent of market values and privatization, a cultural postmodernism, the increase in economic inequality, or the revolution in gender relations, all exactly relate. But they must.

| Tropical Storm Allison » |