National Women's Conference (1977)

I have asked my mother if she recalls the National Women’s Conference, held in Houston in November 1977, but she has only a dim memory, reminding me that my sister was barely more than two years old, and that at the time she was pregnant with me.

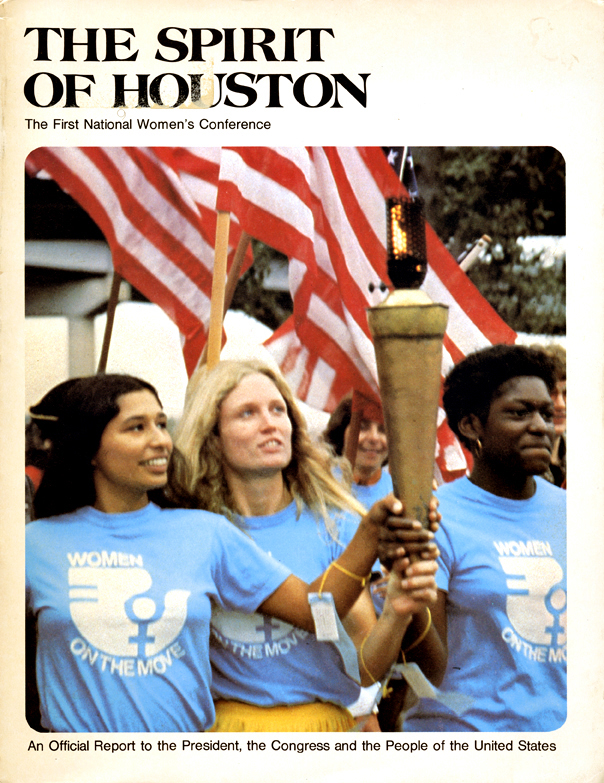

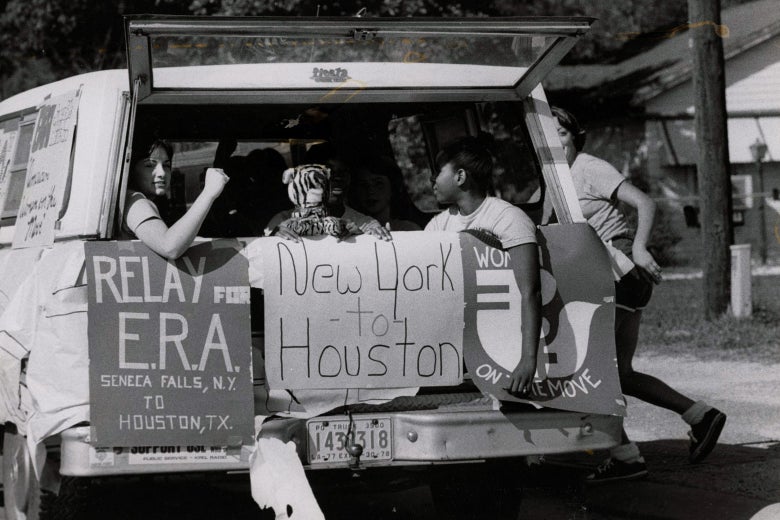

The National Women’s Conference was inspired by the United Nations’ International Women’s year meeting of 1975, held in Mexico City. In 1977, 2,000 delegated appointed by state-level assemblies arrived in Houston to vote on a “Plan of Action” for the US Congress. It would be titled “What Women Want.”

The National Women’s Conference was inspired by the United Nations’ International Women’s year meeting of 1975, held in Mexico City. In 1977, 2,000 delegated appointed by state-level assemblies arrived in Houston to vote on a “Plan of Action” for the US Congress. It would be titled “What Women Want.”

Houston was a fitting site. For a century, the bedrock of industrial society was the male breadwinner and female homemaker family. During the 1970s, it came under severe strain, for many reasons, including feminist aspiration, but one reason was the economic collapse of the male breadwinning wage. Nationally, average male real wages flat lined after 1972. Male labor force participation declined. These two trends continue to this day.

In Houston, high paying, unionized male manufacturing jobs were never central to the city’s labor market to begin with. In a “right to work” state, the refineries were rarely organized, and for the time highly automated anyway. In the late 1970s, the AFL-CIO invested $20 million in the Houston Organizing Project, and successfully organized many government employees, but the campaign collapsed and was pronounced a failure during the early 1980s recession that, with its collapsing oil prices, hit the city hard. In Houston, already during the 1970s, relative to the national baseline, there was a high female labor force participation rate. There was a high rate of divorce. But there was a high rate of remarriage. As Alison Lefkovitz has explained in her recent book Strange Bedfellows, in 1975, Texas, already not only a “right to work” but also a “no-fault” divorce state, became the ninth state to pass a “homemaker entitlement” divorce law, which mandated that divorced dependents received property to compensate for past household labor. In 1972, Congress had passed the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the US Constitution, which declared that “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex,” a liberal feminist aim since the earlier twentieth century. The Texas state legislature ratified the amendment.

In Houston, high paying, unionized male manufacturing jobs were never central to the city’s labor market to begin with. In a “right to work” state, the refineries were rarely organized, and for the time highly automated anyway. In the late 1970s, the AFL-CIO invested $20 million in the Houston Organizing Project, and successfully organized many government employees, but the campaign collapsed and was pronounced a failure during the early 1980s recession that, with its collapsing oil prices, hit the city hard. In Houston, already during the 1970s, relative to the national baseline, there was a high female labor force participation rate. There was a high rate of divorce. But there was a high rate of remarriage. As Alison Lefkovitz has explained in her recent book Strange Bedfellows, in 1975, Texas, already not only a “right to work” but also a “no-fault” divorce state, became the ninth state to pass a “homemaker entitlement” divorce law, which mandated that divorced dependents received property to compensate for past household labor. In 1972, Congress had passed the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the US Constitution, which declared that “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex,” a liberal feminist aim since the earlier twentieth century. The Texas state legislature ratified the amendment.

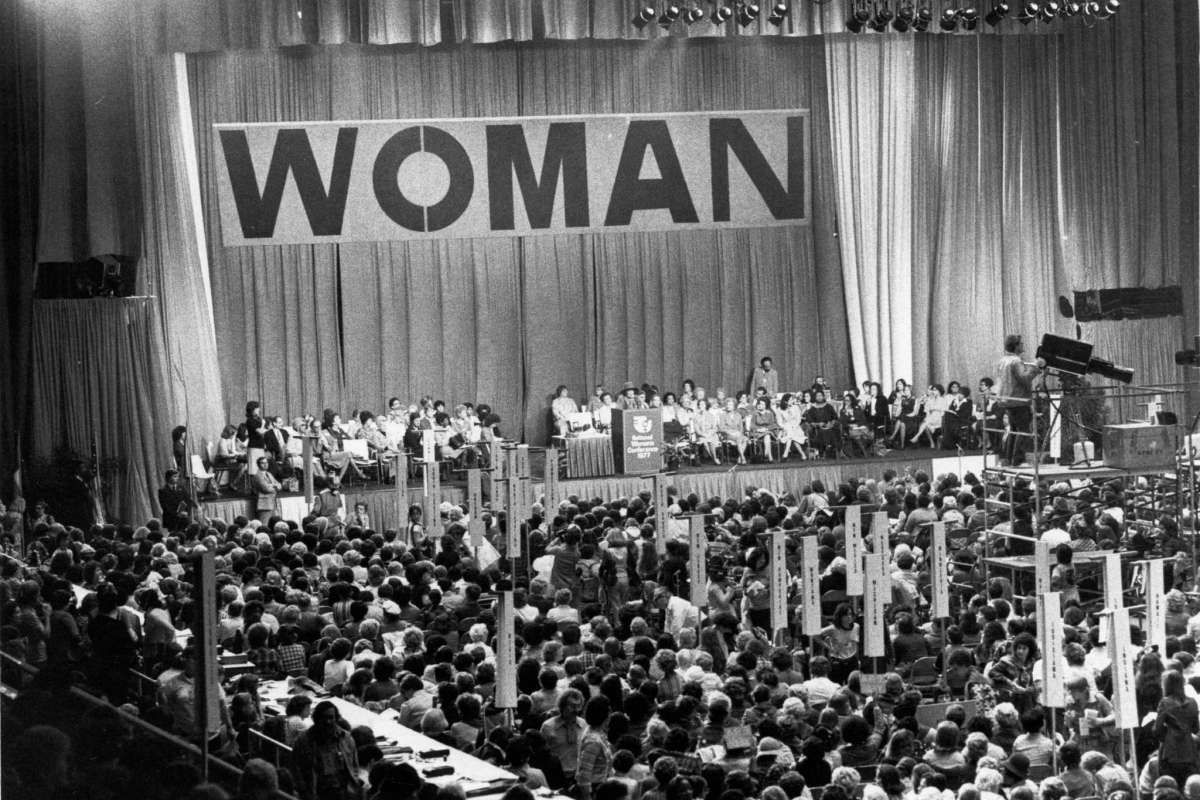

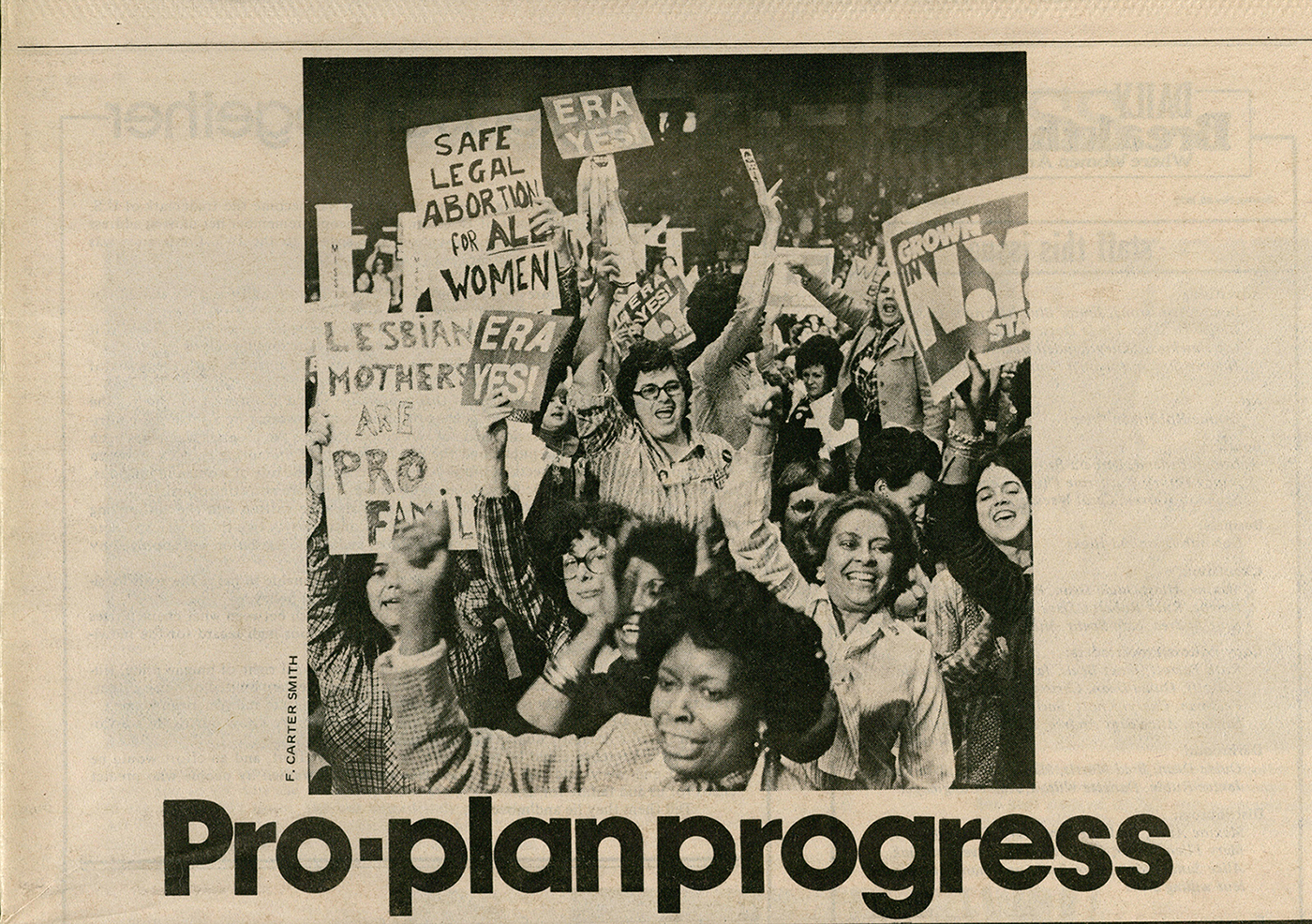

At first, the National Women’s Convention was dominated by conflicts between liberal and radical feminists. Delegates, in the end, voted up 25 resolutions – supporting the ERA, while calling for the end of sex discrimination in the workplace, government supports for “displaced homemakers” in the labor market, and a national “homemaker entitlement” upon divorce. Another resolution demanded marriage reforms “on the principle that marriage is a partnership in which the contributions of each spouse are of equal importance and value.” The most dramatic moment came when a resolution proposed by a Minority Caucus demanding “equal rights” for lesbians carried a majority.

At first, the National Women’s Convention was dominated by conflicts between liberal and radical feminists. Delegates, in the end, voted up 25 resolutions – supporting the ERA, while calling for the end of sex discrimination in the workplace, government supports for “displaced homemakers” in the labor market, and a national “homemaker entitlement” upon divorce. Another resolution demanded marriage reforms “on the principle that marriage is a partnership in which the contributions of each spouse are of equal importance and value.” The most dramatic moment came when a resolution proposed by a Minority Caucus demanding “equal rights” for lesbians carried a majority.

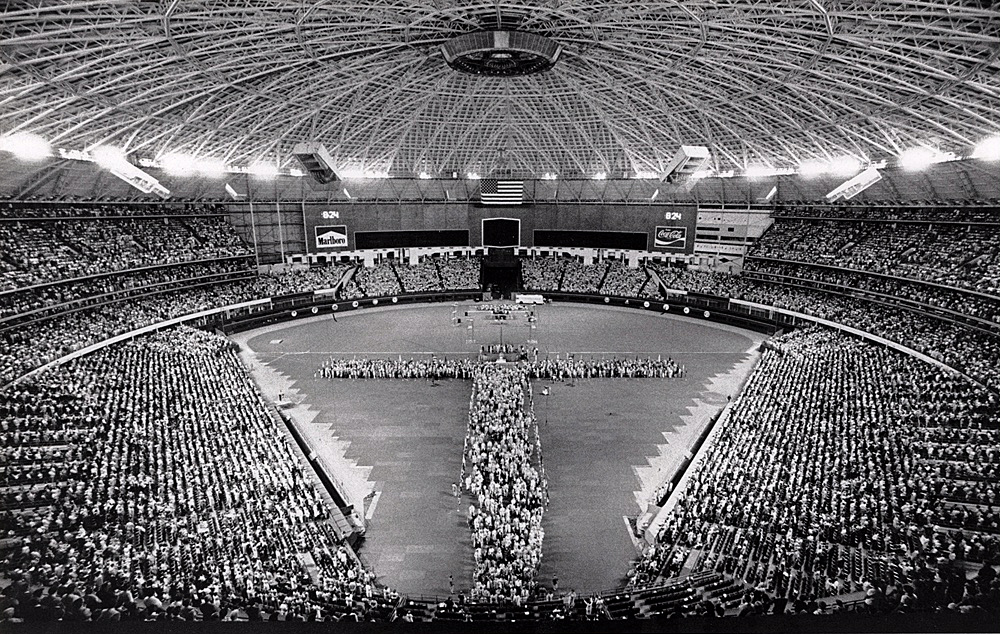

But consequential events were taking place outside the conference, as well. Anti-feminists had organized a counter demonstration outside the Astrodome sports stadium. Lottie Beth Hobbs, a member of the evangelical Texas Church of Christ, was the founder of the anti-ERA group, “Women Who Want to be Women.” Hobbs convinced the conservative “Pro-Family” activist Phyllis Schlafly to come to Houston to protest the National Women’s Conference.

But consequential events were taking place outside the conference, as well. Anti-feminists had organized a counter demonstration outside the Astrodome sports stadium. Lottie Beth Hobbs, a member of the evangelical Texas Church of Christ, was the founder of the anti-ERA group, “Women Who Want to be Women.” Hobbs convinced the conservative “Pro-Family” activist Phyllis Schlafly to come to Houston to protest the National Women’s Conference.

In Houston, Schlafly proclaimed that the family must continue to be “the basic unit of society.” The longtime economic basis of the nuclear family, the male breadwinning wage, may have then been fading, as the gender composition of Houston’s labor market reflected more than most cities. Yet, because of the spatial pattern of urban development, in Houston there was fresh social demand for “family values,” of some kind or another. Because of the sheer newness of the city, the social infrastructure of its neighborhoods – its parent-teacher organizations, community centers – were nonexistent, not finished, or thin. The nuclear family thus bore a heavy burden of sociality, as the “basic unit of society,” if not so much an industrial economy. Meanwhile, economically, due to single-family home sprawl, economic investments in the home, as income generation shifted from labor income to property income, including the asset price appreciation of homes, only increased.

In Houston, Schlafly proclaimed that the family must continue to be “the basic unit of society.” The longtime economic basis of the nuclear family, the male breadwinning wage, may have then been fading, as the gender composition of Houston’s labor market reflected more than most cities. Yet, because of the spatial pattern of urban development, in Houston there was fresh social demand for “family values,” of some kind or another. Because of the sheer newness of the city, the social infrastructure of its neighborhoods – its parent-teacher organizations, community centers – were nonexistent, not finished, or thin. The nuclear family thus bore a heavy burden of sociality, as the “basic unit of society,” if not so much an industrial economy. Meanwhile, economically, due to single-family home sprawl, economic investments in the home, as income generation shifted from labor income to property income, including the asset price appreciation of homes, only increased.

In terms of social life, there were startup “pro-family” evangelical Christian churches in Houston, as well. There may not have been much long-term forward-looking state planning. Relative to the future, there was more evangelical eschatology. All the while, the distance between the scales of family and state was vast. Nationally, with its strong base in sprawling Sunbelt cities like Houston, a “family values” conservatism, sharply critical of state action, arose at this same time.

As for politics, indeed Schlafly would call the 1977 National Women’s Convention a political turning point. Finally, she wrote, in Houston “the ERAers, the abortionists, and the lesbians made the decision to march in unison for their common goals.” The same year, James Dobson founded “Focus on the Family,” and he, Schlafly, and other Christian conservatives would organize a powerful social movement to push the Republican Party to embrace anti-feminism. The next decisive national convention held in Houston, at the Astrodome, was the 1979 Southern Baptist Convention – the so-called “Houston Meeting” – when politically conservative fundamentalists took control of the denomination.

Under their pressure, in 1980 the Republican Party removed from its national platform support for the ERA. After the 1977 Houston Women’s Convention, not another state ratified the ERA, which has never become an amendment to the US Constitution.

| « Transco Tower | Enron » |