Interfaces of Land and Sea

I write this essay in an office in Singapore, where I have just learnt an arresting fact: that in the course of my arrival, via Terminal 3 of Singapore’s Changi Airport, I must have crossed – on foot – the probable spot where, more than 400 years ago, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) Captain Jacob van Heemskerk captured the Portuguese ship Santa Catarina. This incident – richly narrated by Martine van Ittersum in Profit and Principle – was a critical event for international law; from it emerged the brief that became one of the discipline’s foundational texts. While Hugo Grotius wrote Mare Liberum (or The Free Sea) under commission from the VOC, his arguments transcended this specific context to become the accepted doctrine that would long define legal engagement with the ocean.

Yet, over this period, and in an accelerated way in the 20th century, our sense of the physical differences between land and sea have undergone a shift. It is recognized, in the law and outside, that the ocean is akin to land in being divisible and appropriable. Its resources are exhaustible, and cultivation – e.g. aquaculture – is increasingly seen as essential to assure the supply of fish. A dense network of legal rules on access, use-rights, and responsibilities regulates the crowding conglomerations of interests in the oceans. In The Social Construction of the Ocean, Philip Steinberg suggests that ‘great void’ conceptions of the ocean conflict now with the evident and on-going territorialisation of ocean-space.

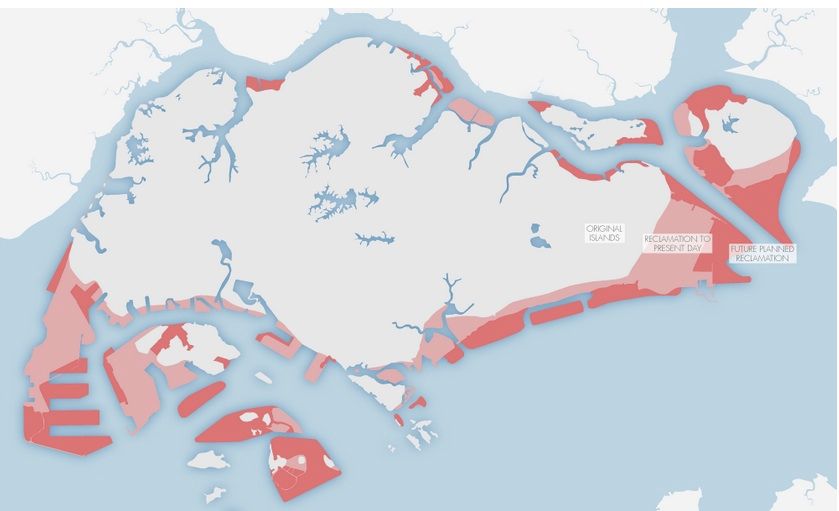

The law has been called upon not only to reflect the resemblances between land and sea, but also address the mutability of the relationship between the two. This mutability may follow as an intended consequence of human enterprise, i.e. projects of ‘reclamation’ such as that which accounts for the site of Terminal 3 of Changi Airport; indeed, Singapore today boasts of a 25% increase of its total land area over the past 200 years due to such projects. It may also follow, however, as an unintended consequence: with rising sea levels betokening the ocean’s own reclamation projects in the opposite direction.

This sequence of essays explores the imprints of climate change, and legal responses to it, within such and other interfaces between land and sea. The changing relationships between them provide evidence of climate change’s causes. They help us visualise also its likely consequences, as the fixed certainties – soil, resources, infrastructure – that govern our imagination of land begin to fall apart. And, they confront us with the irony that these very losses and uncertainties are driving new expectations of, and investments in, the sea.

| Fragile Ports » |