|

|

|

|

|

|

|

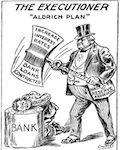

For all of its importance in the domestic and world economies today, very little is known about the practices of the U.S. Federal Reserve System, much less its origins. This paper seeks to identify the economic circumstances that led to the passage of the Federal Reserve Act in 1913 and centers on the banking reform efforts of prominent Jewish-American banker Paul M. Warburg. It will be shown that in the wake of the Panic of 1907 and heightened public resentment towards the banking class, Warburg covertly established the National Citizens League in order to educate the public on the proper principles of sound monetary reform. Furthermore, the paper will explore the impact that public opposition to reserve centralization had on the form the Federal Reserve ultimately took in the U.S.

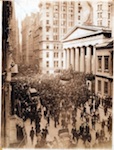

Today, some media critics claim that financial news outlets did not pay enough attention to the roots of the financial crisis until it started to unfold. The way that a newspaper covers a crisis often provides the most direct way to evaluate its business coverage and economic worldview. A newspaper's approach to the economy also speaks to the way its readers view the economy. For these reasons, I decided to contrast the coverage of the Panic of 1907 by The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. In this paper, I explore the two newspapers’ corporate histories and compare and contrast their coverage of specific events in the Panic of 1907. Was one newspaper more pro-business than the other? What did they view as the cause of panics? Did they portray the financial crisis as a supernatural event, or did human beings appear to play a major role in causing the Panic of 1907 to unfold?

With the recent bail out Bear Sterns, the utilization of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), and the decrease in the federal funds rate to a target range of between 0.00% and 0.25%, the Federal Reserve has taken a significant role in the current financial crisis and generated public discussion concerning the proper role of the Federal Reserve. But how did bail-outs and liquidity injections occur before the creation of the Federal Reserve? Coordinating the bail-out of the Knickerbocker Trust, Moore & Schley Brokerage House, and the New York Stock Exchange, John Pierpont Morgan, founder of J. P. Morgan & Co., served as a type of lender of last resort in the Panic of 1907. This paper seeks to explore the role of J. Pierpont Morgan in the Panic of 1907 and trace the change in public opinion surrounding him and other wealthy financiers during the Pujo Trials in 1912 and 1913, which sought to investigate the "money trusts" of 1907.

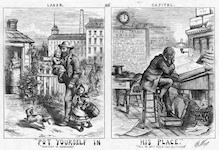

Given the present economic climate, many people have recently raised concerns about executive compensation practices at large corporations in the United States. This paper traces these practices back to their origins at the dawn of the 20th century and examines economic arguments about pay and bonuses for company executives at several of the largest American corporations between 1890 and 1940. While companies were not required by law to disclose their compensation practices to the public until 1934, this paper draws on a variety of primary documents to establish a picture of how many companies and executives doled out lavish bonuses to the lucky few at the top of the pay ladder. The examination concludes with the events of 1934 that led to federal requirements that all companies disclose executive compensation statistics, and the impact these new requirements had.

|

|

The Center for History and Economics is not responsible for the All content (c) 2010 President and Fellows of Harvard University.

|