White Coal and New Continents

Energy has often featured as a central element in the imagination of utopian societies – whether as efficient labor, boundless food stocks, or new sources of power. Conversely, utopian impulses have often come to the fore during times of actual or predicted energy transitions, inspiring designs for the reorganization of socio-economic, political, and environmental conditions.

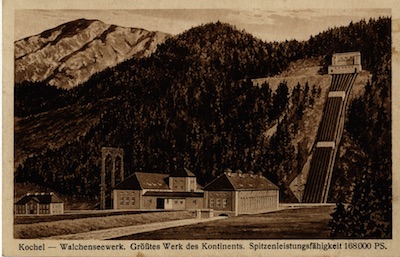

Postcard picturing the Walchenseewerk, c. 1923

In the early twentieth century, hydropower sparked some of most spectacular ideas about not only the future of energy, but the future of civilization. Ever since the long-range transmission of electricity had become industrially and economically viable around the turn of the twentieth century, “white coal” inspired designs of ever-larger hydropower stations. Specialized journals and magazines cropped up in various European countries, and the World Exhibitions promoted the last technological advancements in the field of hydropower.

Far removed from the wooden watermills of the pre-industrial era, hydropower presented itself as a technology at the forefront of progress: the production sites, with impressive dams and oversized turbines, were feats of modern engineering, presented to the world in magazines, films, and on postcards. Proponents advertised “white coal” as clean, scientific, inexhaustible, and as a social palliative – the few highly trained specialists needed to run a hydropower station stood in stark contrast to the masses of exploited and strike-prone workers of a coal mine. The atmosphere was conducive to visions of what the full use of the world’s hydropower potential might accomplish. And it even led to projects of expanding the potential. This was the central objective of the 1920s plans of Herman Sörgel, a German architect who proposed a radical solution to the tensions and conflicts of the crisis-ridden interwar years in Europe.

Atlantropa

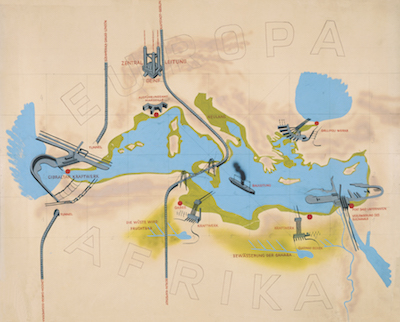

Map of the Atlantropa Project, c. 1928Atlantropa (originally called Panropa) was many things at once: a precocious attempt at European unification, a geopolitical master plan to unite Europe and Africa, and a futuristic vision of land reclamation and climate engineering on a continental scale. All of these transformations, however, were dependent on the project’s central feature, which became almost synonymous with its name: Atlantropa was designed around the largest hydropower station the world had ever seen. Sörgel’s grand idea was to isolate the Mediterranean Sea with a giant dam at the Strait of Gibraltar and smaller dams at the Suez Canal and Gallipoli. Slowly but steadily, evaporation would lower the water level of the now enclosed Mediterranean and lead to a buildup of potential energy across the Gibraltar dam. Hydropower generators could then transform the potential energy into enormous amounts of electricity – the initial calculations estimated about 120 GW, or about a thousand-fold increase over the Walchensee Power Plant in Bavaria, one of the largest hydroelectric power stations in Europe at the time.

This energy, Sörgel argued, would be able to transform North Africa and turn desert into fertile land – both by desalinating water from the Mediterranean for irrigation and by creating an amelioration of the climate through the construction of giant reservoirs that would increase evaporation and, eventually, precipitation. Beyond these plans for environmental transformation and economic exploitation, Sörgel believed that the availability of almost limitless amounts of energy would also be able to overcome political divisions within Europe and halt the all-encompassing decline of the environment and society, which Oswald Spengler had conjured up in his writings. Atlantropa was to herald a new society of the occident, a new order built on technocratic principles and the primacy of hydropower.

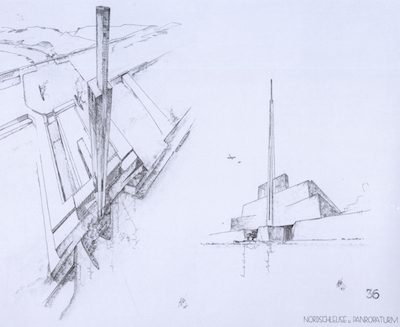

Peter Behrens, designs for the northern lock and a tower at the Gibraltar Dam, 1931

Despite the unprecedented and utopian scale, the plans were more than the expression of an eccentric mind. Both Sörgel’s anxieties about environmental decline and resource exhaustion and his belief in the absolute primacy of technology reflected contemporary debates and struck a chord with the German public. Newspapers avidly reported about the project, modernist architects worked on designs for some of the engineering structures, and geologists debated the possible consequences of the transfer of large water masses from the Mediterranean to the interior of Africa. Atlantropa thus stands as a striking example of both the entanglement of environmental and political ideas in interwar Germany and the still understudied history of the unrealized utopian projects of high modernism.

Related Publication:

Philipp Nicolas Lehmann, “Infinite Power to Change the World: Hydroelectricity and Engineered Climate Change in the Atlantropa Project,” The American Historical Review (2016) 121: 70-100.

Philipp Lehmann is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin. He received his PhD from Harvard in 2015, and was the research coordinator of the Global History of Energy program at the Harvard Center for History and Economics from 2012 to 2014.