Bellaire v. Baytown Lee (1994)

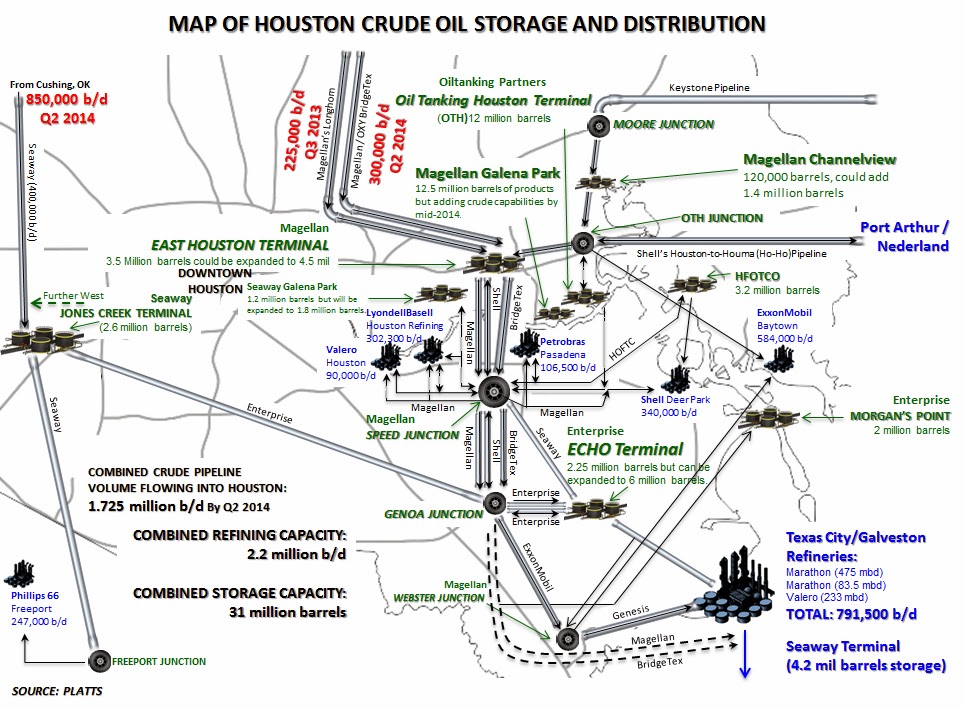

Baytown is an industrial city of about 70,000, located 26 miles east of Houston, along the Houston Ship Channel, at the confluence of Galveston Bay, the Buffalo Bayou and the San Jacinto River. ExxonMobil’s Baytown Refinery, which dates from 1919, is today the third largest refinery in the US and the eighth largest in the world (just slightly behind a Saudi Aramco facility in nearby Port Arthur, Texas and a neighboring Marathon plant in Texas City, Texas).

Baytown is an industrial city of about 70,000, located 26 miles east of Houston, along the Houston Ship Channel, at the confluence of Galveston Bay, the Buffalo Bayou and the San Jacinto River. ExxonMobil’s Baytown Refinery, which dates from 1919, is today the third largest refinery in the US and the eighth largest in the world (just slightly behind a Saudi Aramco facility in nearby Port Arthur, Texas and a neighboring Marathon plant in Texas City, Texas).

I have been to Baytown on a few occasions, the most memorable being the 1994 Texas high school baseball regional semifinals, a match-up between Bellaire High School, my team, and Baytown’s Robert E. Lee High School.

Following the script from Friday Night Lights – which was based after all on the actual west Texas high school football rivalry between Midland and Odessa (where the Bush family stopped over, in between Connecticut and Houston) – Bellaire, from the more affluent west side of town, was West Dillon, while Baytown Lee, a working-class enclave, was East Dillon. At the time, however, I did not think of it in these terms.

What I did think, back in 1994, was that the game was important, really important. But why? One reason is that baseball is a great game, and I loved playing it. But, still, why had youth sports become so crazy in Texas? High school football was always popular in Texas, especially in rural parts. But something else was beginning to happen during the 1980s and 1990s – obsessed parents, consumed communities, “select” or “traveling” teams, individuals who made a living by coaching amateur sports teams or giving lessons to 9-year olds. Obviously, youth sports was yet another postindustrial service labor market. If in Houston commercial venues tied to the service economy, like shopping malls and restaurants, were adopted for purposes of sociality, meanwhile activities like youth sports became newly commercialized.

Indeed, returning to the sparse layout of Houston, sports joined shopping and eating out (a common practice, given the weak male breadwinning wage and the high rate of female employment) as things to do. This is another variant of the “free enterprise myth.” As much as the history of Houston is about the free play of market forces, it is about the appropriation of commercial spaces by the residents of the city for noncommercial purposes. The baseball field was a public space, a place where genuine fraternization and community happened – another social outcropping of the postindustrial urban landscape.

Then, there was the rise of late twentieth-century inequality. This face of it was another, less evangelical and conservative, expression of “family values.” Well-off parents, or even middle-class parents fearful of their children’s downward mobility, as the gap between rich and poor began to widen in the late twentieth century, stretching at the middle, began to take new kinds of interest in their children’s lives, to afford them a leg up, or to develop their taste for competition and meritocratic battle – all emotional and financial investments in their children’s “human capital,” which was then replacing industrial capital in social and economic dynamics. Bellaire High School, a public school, educated the children of precisely this kind of upper middle class in the 1990s, although more recently the school has declined, as more private schools have increasingly captured the loyalty of the city’s affluent. In other words, by the 1990s amateur baseball had become a class phenomenon.

In 1994, we traveled to Baytown to play a regional semifinal game. Our high school baseball program was very good, at the time the best in the state of Texas, led by a fantastic coach, Rocky Manual, yet another transplant from the deindustrializing Midwest. We usually won. That year, we would go on to win the Texas state championship.

Baytown Lee was not as good. Baytown was a factory community, in the industrial sense, but relative to the gutted factory communities of the Northeast and Midwest it was doing all right economically. In postindustrial Houston, because of the oil refiners a version of the industrial, if more automated and less unionized, persisted, and even flourished. Across the 1980s and 1990s, poverty declined in Baytown, and median incomes rose, if not as dramatically as at the top of the Houston income distribution. By contrast, they were flat lining or collapsing in the factory communities of cities like Pittsburgh or Detroit.

Baytown Lee was not as good. Baytown was a factory community, in the industrial sense, but relative to the gutted factory communities of the Northeast and Midwest it was doing all right economically. In postindustrial Houston, because of the oil refiners a version of the industrial, if more automated and less unionized, persisted, and even flourished. Across the 1980s and 1990s, poverty declined in Baytown, and median incomes rose, if not as dramatically as at the top of the Houston income distribution. By contrast, they were flat lining or collapsing in the factory communities of cities like Pittsburgh or Detroit.

The stands were packed that day in Baytown. Early in the game, the bleachers began to tremble. They shifted to the right, and then collapsed. A 6-year old girl playing beneath the stands, Jennifer Sutton, was crushed and died. Seventeen others were injured, including Jennifer’s 9-year old brother, hurt while trying to reach her in the rubble. “I just heard a bunch of screams and it fell like a deck of cards,” said Baytown Lee’s third basemen Keith Hart the next day in the newspaper. “Me and the rest of the players rushed over and tried to free the little girl. We tried our hardest. It took about 30 seconds but seemed like forever.”

It was a tragic accident, and the game was canceled that day. But soon, the game resumed. I honestly could not remember how soon. I know I pitched in it, though. To jog my memory, I glanced through the Baytown Sun and other local papers. They covered the accident. It turns out they were also covering the steady drumbeat of workplace accidents, including the loss of life, in Baytown’s refineries. Most failed to register in the Houston Chronicle, although the death of the young girl at the baseball game did, as did the major Ship Channel accidents of that time – a Phillips Petroleum Co. plastics plant explosion that had killed 23, an Atlantic Richfield chemical plant accident that killed 15. Judging from the Baytown Sun, yet another burgeoning service profession of the 1990s was industrial accident plaintiff attorney.

Over the past few years – far more than the Houston Chronicle – the Baytown Sun has devoted many pages to the topic of climate change, reporting on a running debate in the community over whether global warming is a “hoax.” The tone is often sarcastic, betraying resentment. Why trust the state to predict and plan the future, when “Al Gore couldn’t predict tomorrow much less 'global warming'.” Then, “Some of us remember BAC when (Before Air Condition) there was no relief from the Texas heat. I think it was just as hot fifty years ago as it is now, although there are those global-warming pundits who would disagree.” “After reading Jon Powell’s version of climate change reasoning you wonder how so many people make a living promoting climate change and the world just accepts it.” “To me, this geographic area is in grave danger from environmental hazards and climate change. I hope we transition to other fuel sources sooner rather than later, but I'm sure that the area refineries and plants will continue to operate and pollute until the last drop of petroleum has been refined.”

The Baytown Sun polls its readers. Does climate change exist, and is at least partly caused by human activity? In national polls, in recent years about two-thirds of Americans have said that global warming is caused by mostly human-related activities (a low, outlying number at the global scale, apart from Saudi Arabia and Indonesia). The Baytown Sun’s informal polls actually reveal roughly the same number, two-thirds. But my sense, anecdotal to be sure, is that there is much more anger and aggression on both sides of the issue in Baytown. On a personal and family scale, a life spent working in the refineries, or being dependent upon one who does, must familiarize one with the possibility of catastrophic risk, including loss of life – perhaps a source of irritation, even anger. Yet, to ignore such risks, maybe even embrace them, for many people may be what it takes to affirm the worth of their lives and community, if only to make the losses worth it.

The readership of the Baytown Sun is an aging one, and for many it is probably too late to feel differently about the subject.

| « Enron | Texas Medical Center Master Plan » |