Cy Twombly Gallery (1994)

In addition to the Texas Medical Center, another manifestation of philanthropic wealth in Houston is museums, all of them nonprofit corporations of course, amply funded by bequests from oil-related enterprise. The most striking is the Menil Collection.

Dominique de Menil was born Dominique Isaline Zelia Henriette Clarisse Schlumberger. Her father and uncle founded Schlumberger Limited, the largest oilfield services corporation in the world. Dominique, after a short stint as a film screenwriter in Weimar Berlin, married the banker Jean de Menil (later John). When the Nazis occupied France, the couple fled, ultimately settling in Houston where de Menil ran the Middle East and Latin American branches of Schlumberger.

The Menils became great advocates, in equal measure, of civil rights and modern art. Housing their private collection, open to the public at no cost, the Menil Collection first opened in 1987. It was the first US building designed by the Italian architect Renzo Piano.

In 1992, the Menils commissioned Piano to build a gallery dedicated to the work of the artist Cy Twombly. It opened in 1994.

|

|

Twombly, born in Virginia in 1928 (he died in 2011), came of age at the tail end of postwar abstract expressionism. He fled its scene in New York City, however, for a life as an ex-patriate in Rome. The Cy Twombly Gallery, designed in conjunction with the artist, is modeled after the Palazzo Farnese in Rome – a very, very long way from Texas. I visited the gallery after it opened and wondered what business it had being in Houston. But now, I know.

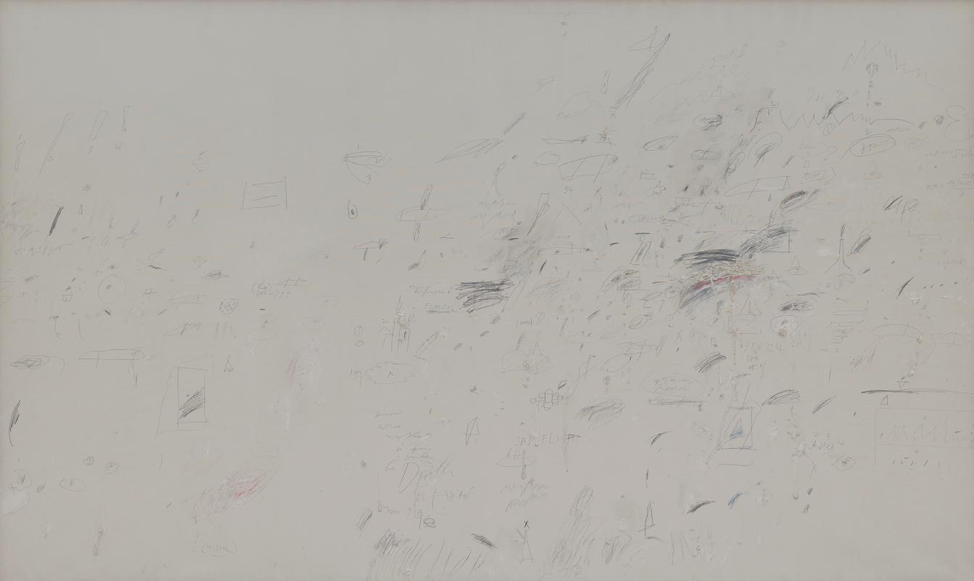

Upon entering the pavilion, the first painting to the left is The Age of Alexander (1959-1960). After Twombly moved to Rome, he studied antiquity, especially Greek and Roman mythology. Scale became one of Twombly’s artistic mediums and themes, including the epic. The Age of Alexander is a 9 feet x 16 feet canvas.

The painting displays many of Twombly’s recurring motifs, including vastness, conveyed in blank white and cream spaces, marked, in the words of one critic, by “delicate notional episodes and graphic outbursts.” Twombly commonly drew words, phrases, and poems on his canvases. On the bottom center of The Age of Alexander there is scrawled, “FLOODS.”

Given the painting’s epic scale, and that many of Twombly’s paintings refer to classical figures and events (Nine Discourses on Commodus, Ides of March, Pompey appeared shortly thereafter), often The Age of Alexander is thought to refer to Alexander the Great, especially since another canvas scrawl reads “Why cry anymore?” a seeming reference to the apocryphal story that when Alexander the Great realized he had no more worlds to conquer, he sat down and wept. But it is also possible the reference is to Twombly’s one year-old son, Alessandro, who may well have been crying on the New Year’s Eve during which Twombly painted the entire work, and that the painting is a window into the anxieties of first becoming a father.

This is what much of Twombly’s art is about. It relates the most personal and intimate of scales with the grandest of historical, even mythical ones – and sometimes scales in between. In his library, Twombly owned four editions, in three different translations, of C.P. Cavafy’s poem “The City.” “You won’t find a new country, won’t find another shore. / This city will always pursue you.”

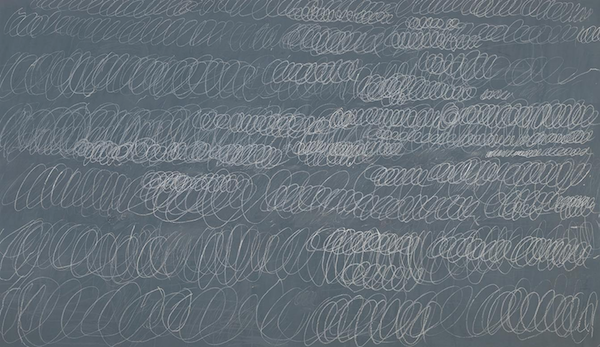

If The Age of Alexander is to the left, to the center on entering the gallery is a group of the so-called “chalkboard” paintings, for which Twombly is most famous.

Their most likely inspirations are the “deluge drawings” of Leonardo da Vinci. Water “is the driver of nature,” said Da Vinci, who made close studies of storms. With water, “without it, nothing retains its form.”

|

|

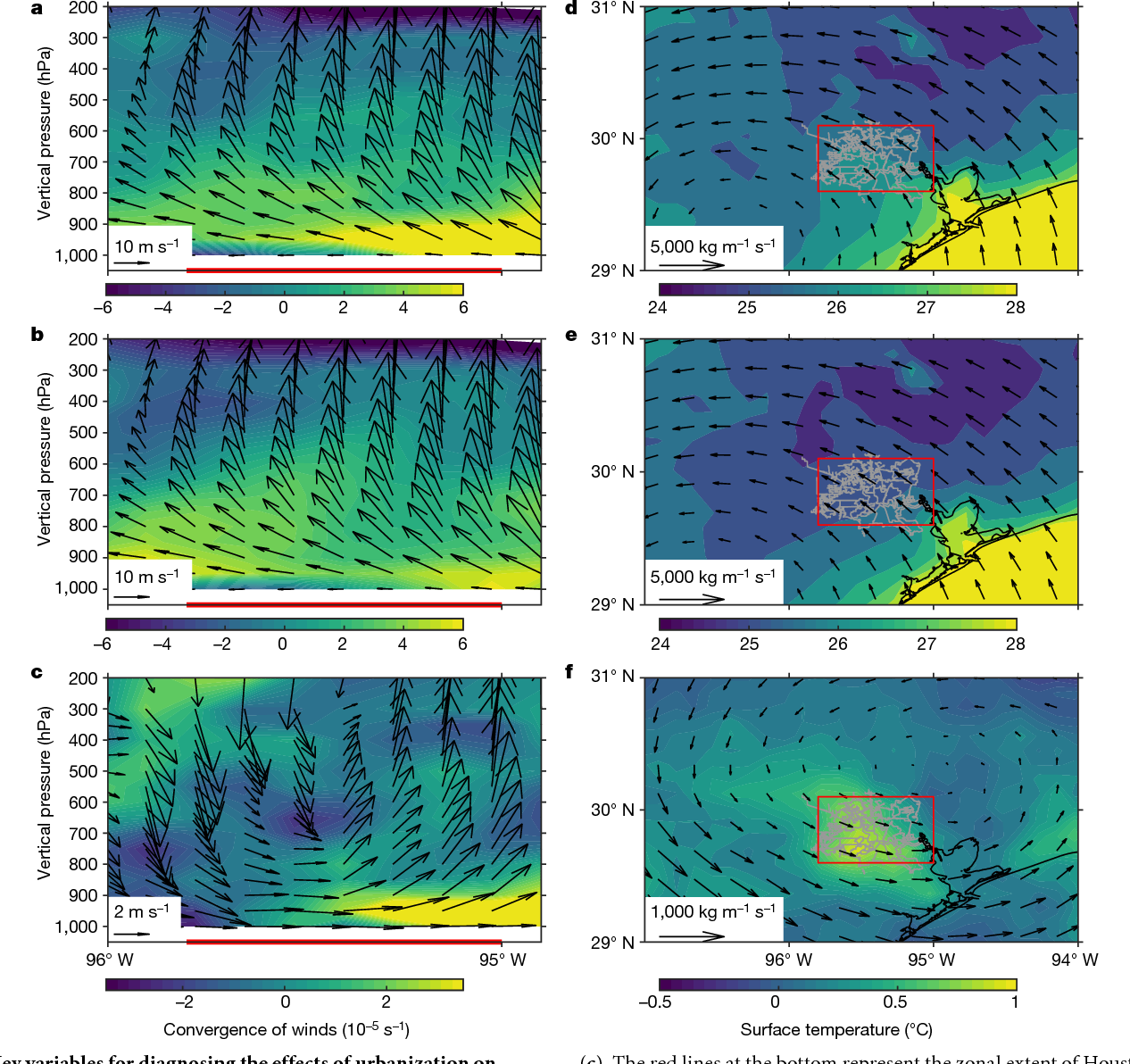

Then, there is another visual resemblance, the one between these images and many of the graphs that climate scientists have used to demonstrate how human-induced climate change strengthens storms and floods in Houston.

Then, there is another visual resemblance, the one between these images and many of the graphs that climate scientists have used to demonstrate how human-induced climate change strengthens storms and floods in Houston.

Not coincidentally to my mind, Twombly first began to paint the chalkboard series in 1966, the same year as the epic flood of the Arno River that put twenty feet of water on top of the city of Florence, where Twombly would travel in 1968 to make a special study of Da Vinci’s drawings.

Not coincidentally to my mind, Twombly first began to paint the chalkboard series in 1966, the same year as the epic flood of the Arno River that put twenty feet of water on top of the city of Florence, where Twombly would travel in 1968 to make a special study of Da Vinci’s drawings.

When I was in Florence visiting at Scuola Normale Superiore in 2018, and I walked along the banks of the Arno just outside the city, I saw that on the Arno Floodway the banks of the river had been channeled, graded, and even lined with concrete to control floods in the exact same manner as Houston’s Brays Bayou – the same civil engineering project, from the same postwar decades. Florence started on it after a 1949 flood but did not finish in time for the 1966 deluge. This may be the first and last time the cities of Houston and Florence will ever be compared as similar!

|

|

Back in 1504, Da Vinci first proposed the project in concert with the Florentine government’s Second Chancellor at the time, Niccolo Machiavelli.

“Fortune is a river,” Machiavelli once said.

Meanwhile, yet another interpretation of the chalkboard paintings is that Twombly’s father was a former professional baseball player. Here, empty spaces punctuated by activity on Twombly’s canvases resemble, according to Joshua Rivkin’s recent Chalk, baseball, or “a slow game punctuated by bursts of activity.” Chalk used to draw the paintings recalls the chalk of the baselines and batters box, and the “cursive open loops of white” resemble “the ball loping and winding through the air.”

Next, to the right, is arguably Twombly’s greatest work, Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor (1994) – although I am also partial to the Bacchus series (2003-08), on the US invasion of Iraq, in which the white chalk is replaced by dripping blood-red paint, which, given its oil theme, should be in Houston, but is not. It took Twombly 22 years to complete Say Goodbye. It is 157 ½ feet tall and 624 feet wide.

Next, to the right, is arguably Twombly’s greatest work, Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor (1994) – although I am also partial to the Bacchus series (2003-08), on the US invasion of Iraq, in which the white chalk is replaced by dripping blood-red paint, which, given its oil theme, should be in Houston, but is not. It took Twombly 22 years to complete Say Goodbye. It is 157 ½ feet tall and 624 feet wide.

Once again, epic and personal blend, as do personal history and myth. Catullus, the first-century BCE Roman poet, who lived during the late Roman Republic, was known during his lifetime for having dismissed epic poetry in favor of poems about himself and his friends. He spent a summer posted in Bithynia, a Roman province on the Bosporus, before he said goodbye to the shores of Asia Minor. The painting moves right to left, westward back to Rome, depicting a journey and a life cycle on an extravagant scale. It is not possible to look at all of it all at once, and take it all in (kind of like, given the vastness of its space, Houston). There are scales that simply overwhelm, because they are larger than life, yet are still somehow located in a single life.

I think I know the painting Say Goodbye very well, and not only because I have spent a lot of time standing in front of it (including every time I go back to Houston, and I now always take my father with me to see it). In it, Twombly uses many of his typical colors, including reds, pinks, and purples, common to other paintings in the gallery.

|

|

These colors are familiar to me, since Twombly passed many years painting at his home and studio in Bassano, Italy, which is about an hour north of Rome, near Lake Bolsena, a small region of Italy in northern Lazio called Tuscia, where I myself now every year spend many months with my partner and her family. I recognize a very particular green landscape, in the series of Pond Paintings from the 1980s in the next room of the gallery after Say Goodbye, as well as, in Say Goodbye and in other paintings, the distinctive colors of Tuscia, in particular of a Lake Bolsena sunset.

Back to Houston. Twombly’s first series of Lake Bolsena paintings took NASA’s Apollo 11 moon landing as its subject – Twombly thus tackled the planetary scale in the distinctive language of his art, which, at the same time as it evokes grandeur, attempts, as an Italian art critic noted early in Twombly’s career, “to put down unconscious mind.”

Back to Houston. Twombly’s first series of Lake Bolsena paintings took NASA’s Apollo 11 moon landing as its subject – Twombly thus tackled the planetary scale in the distinctive language of his art, which, at the same time as it evokes grandeur, attempts, as an Italian art critic noted early in Twombly’s career, “to put down unconscious mind.”

In the region of Italy where Twombly painted, a deep sense of time is inescapable. In the volcanic soils near Lake Bolsena, farmers plowing the fields still turn up pottery and other artifacts from the Etruscans, an ancient pre-Roman civilization. The Romans arrived, and wiped them out. A civilization was lost. In this same area, many Romans from Catullus’s time, the late Republic, had villas. But the republic was lost. Cities were lost, too. Near Twombly’s house in Bassano, the warring commune of Viterbo destroyed an ancient Roman city, Ferranto, as recently – on this measure of time – as the twelfth century. Although it has a mythical origin as the “free enterprise city,” it is hard to think of Houston on this scale. The city is so recent. Its largeness comes not in time, but in space.

But it is a city that is as much an expression of an entire civilization as any other, measured at the scale of geological time: the civilization of the Anthropocene. It is a city and a civilization that one day could be, and maybe should be, lost, too.

The Menils’ commitment to a permanent Twombly gallery was a brave one at the time it was made. For, during the late twentieth century Twombly’s art was not very popular. On the one hand, as Richard Serra, whose steel and iron sculptures have used public space to call attention to qualities of the industrial epoch, complains, “Is the subject matter the content of the painting? Or is the subject matter Twombly? In Twombly’s paintings it seems to me that the subject matter is Twombly himself, and the content of the painting, you can’t decipher.” On the other hand, during the 1980s and 1990s, the era of Houston’s rise, when cultural postmodernism was critiquing the possibility of “grand metanarrative,” deconstructing every and all sweeping claim, Twombly was taken to task by another critic for choosing “to live among the mouldering palaces and antiquities of Europe,” and for being, in his focus on the unconscious, “dirty minded,” while at the same time obdurately “history-minded.”

The Menils’ commitment to a permanent Twombly gallery was a brave one at the time it was made. For, during the late twentieth century Twombly’s art was not very popular. On the one hand, as Richard Serra, whose steel and iron sculptures have used public space to call attention to qualities of the industrial epoch, complains, “Is the subject matter the content of the painting? Or is the subject matter Twombly? In Twombly’s paintings it seems to me that the subject matter is Twombly himself, and the content of the painting, you can’t decipher.” On the other hand, during the 1980s and 1990s, the era of Houston’s rise, when cultural postmodernism was critiquing the possibility of “grand metanarrative,” deconstructing every and all sweeping claim, Twombly was taken to task by another critic for choosing “to live among the mouldering palaces and antiquities of Europe,” and for being, in his focus on the unconscious, “dirty minded,” while at the same time obdurately “history-minded.”

Today, given growing consciousness of anthropogenic climate change, Twombly’s efforts to operationalize the grandest scales, from the deep time of the planetary and the geological, to the timelessness of myth and the unconscious, look better, even more urgent. Through his art, Twombly moved across scales of vast difference and kind, attempting, even if not always succeeding, to achieve the satisfactory unity of a single work of art. It says something about the difficulty of such an attempt that it took an artist of rare genius to strike these kinds of connections – the kinds of connections necessary to make sense of a problem like climate change. Thus far, our politics, our ethics, our senses of self, as well as our history writing, have not so succeeded.

If the Cy Twombly Gallery, like everything else in Houston, does not directly address climate change, nonetheless it is always about climate change.

| « Texas Medical Center Master Plan | Should Houston Exist? » |