Texas Medical Center Master Plan (1999)

Today, the Texas Medical Center (TMC) is “the largest medical complex in the world,” a category of competition first invented, it seems, by the TMC itself some time during the 1980s.

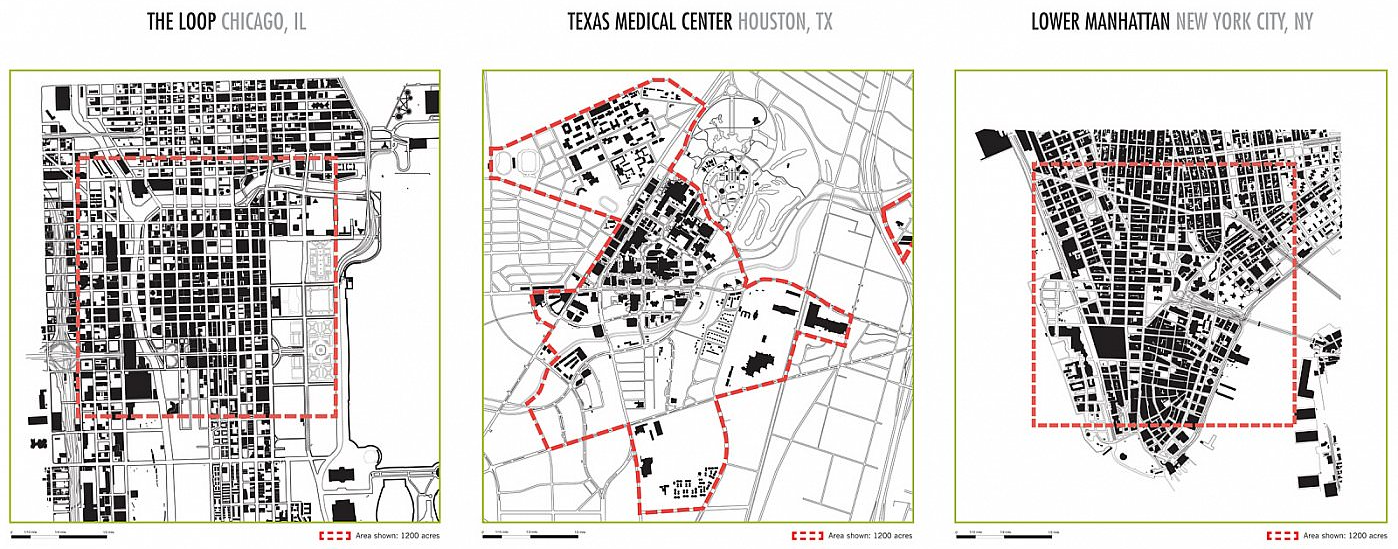

To give some sense, the TMC is about the size of lower Manhattan, or the Chicago Loop.

What distinguishes the TMC is that it is nearly a city unto itself.

|

|

Actually, the TMC is a corporation, chartered by the state of Texas in 1945, and, being of the nonprofit type, restricted to “benevolent, charitable and educational purposes.” Until far into the nineteenth century, many American cities were chartered corporations. So it is not that unusual, historically speaking, for a corporation to possess a governing mandate. In the era of privatization, corporations, both for profit and not, have been tasked with more and more governing. The for profit real estate firms that developed Houston figure here, as do the powerful energy corporations that have shaped the city’s agenda and fate. Best representing the nonprofit corporation’s prominence is the TMC.

The current campus of the Medical Center was supposed to be a public park.

In 1936, M.D. Anderson, a founding partner of the largest cotton merchandizing firm in the world, founded a charitable trust in his name, and when he died three years later the trustees decided to match a $500,000 appropriation from the Texas state legislature to fund a cancer hospital. The first site was “The Oaks,” named after its live oak trees, which was the former estate of Captain James A. Baker, but in 1943, after a citywide referendum in which only 951 votes were cast, the trust bought a 134-acre plot of land that the municipality hived off for it from the city’s Hermann Park. In 1959, the Texas legislature voted to grant the nonprofit corporations the power to take property under eminent domain. After acquiring still more land, the TMC by now has developed more than 1,150 acres.

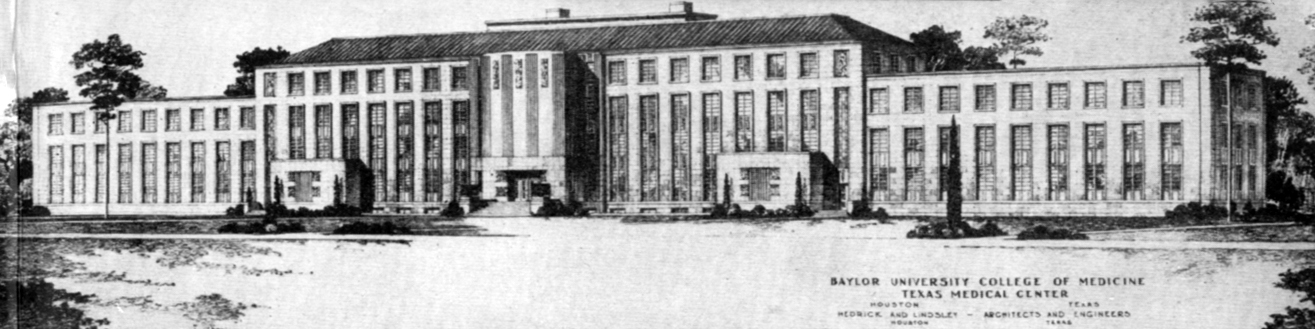

The TMC’s original design was a mix of college campus, evoking Rice University next door, and the private, deed restricted white subdivision.

The original buildings all faced inward, as if to seal the campus off from the city. When the county built Ben Taub General Hospital in the early 1960s, serving many poor African-Americans, it faced outwards, with a fence separating it from the inner campus (removed only in 1985).

In US cities that once had public health care systems, and other public services, late twentieth-century privatization represented a transformation from public into private. But in Houston many public institutions never existed to begin with, as the city itself largely did not. And, here is another dimension of Houston’s “free enterprise city” myth. Privatization has consisted not only of turning things over to the market and the profit motive. It has also meant bestowing a proliferating number of nonprofit corporations with public tasks. The TMC is a nonprofit of nonprofits. It has 55 members today, which joined the TMC after agreeing to maintain a nonprofit status in perpetuity. For that, members received a plot of land (until the 1980s, through an outright transfer, after that leased for 99 year renewable terms for $1 per year) upon which to construct a facility. But the TMC, for instance, has also granted land to a Veterans Administration Hospital, and a number of state university medical schools, among other public entities that benefit from its largesse and supervision. Until 1985, the city of Houston’s Health Department was located on a TMC plot of land. On its campus, the corporation has been responsible for streets, power generation, drainage, water lines, and a police force.

Meanwhile, the TMC represents one of the city’s great economic anchors. During the 1980s recession, when oil prices fell and the city’s economy stalled, TMC infrastructural spending provided a nonprofit stimulus. Construction commenced during the next phase of the city’s breakneck growth during the 1990s.

The TMC today employs over 100,000 persons (in the past decade the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) has made some organizing headway). This is a common, postindustrial urban phenomenon, as the work of Gabriel Winant is illustrating. In the service economy, health care, often for aging industrial workers, predominates, and hospitals too become service economy sites appropriated as venues for sociality. The TMC, for instance, employs thousands of volunteers.

Still, while the TMC boasts of being “the largest life sciences destination in the world,” Houston has never seen the growth of a more entrepreneurial biotech industry, like Silicon Valley or Boston’s Route 128. One reason is the TMC’s assiduous adherence to its nonprofit restrictions. Silicon Valley’s biotech industry is attributable to the many transpositions between nonprofit and for profit domains, with Stanford University an active catalyst (Rice University has not played such a role). The TMC’s charter says any member institution that strays from nonprofit will have their land taken back. Tellingly, in 1996 in the courts the corporation blocked a proposed merger between St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital and the (truly venal) for profit hospital conglomerate Columbia/HCA on the grounds that it violated the nonprofit deed restriction. In their mentality, the city’s wealthy oilmen have maintained a sharp split, between often freewheeling profit making and virtuous philanthropy. After Enron’s demise, a Houston Chronicle headline read, “Enron's demise leaves huge void for area's nonprofit community,” including for the TMC. In this morality, one opposite balances out the other, if it does not compensate for it. In a city where public and private “partnerships” are celebrated and whose institutions are otherwise so porous, this is one fixed line.

And so, despite its economic presence, where the TMC’s own initiatives have mattered the most is in governance. After so much construction and growth across the 1990s, the city’s Enron-era boom, the TMC decided to develop its first “master plan.” Robert Scott, vice president of planning and development, and head of the TMC’s “Forward Planning Committee” hired Skidmore, Owings & Merill, a Chicago-based architectural firm, and the result was A Vision for Growth: A 50 Year Master Plan for the Institutions of the Texas Medical Center, Houston.

From a nonprofit, this was Houston’s most ambitious long-term planning document to date. As Scott put it, “We were not a government, but we functioned like a quasi city government…. I was the director of public works.”

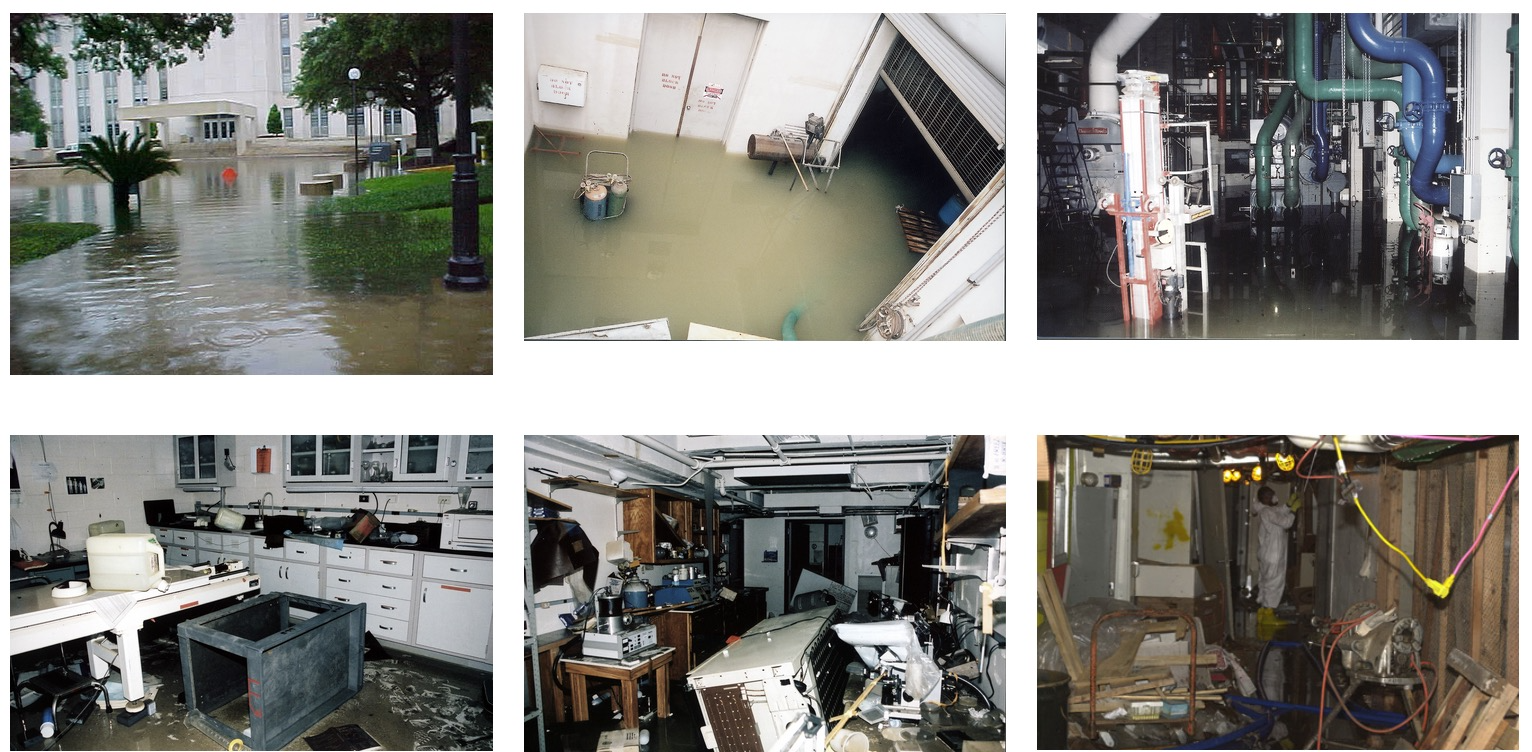

The main result of the new master plan was a $40 million plan to rebuild roads and pipes, funded by a tax-exempt TMC debt issue in the municipal bond market. But then, in June 2001 Tropical Storm Allison hit. The 1999 master plan had not said much about flood control. The TMC was built over Harris Gully, which drains a large portion of the city south, into Brays Bayou.

In 2001, the TMC suffered $2 billion damage. Electrical stations imprudently placed in basements flooded. 30,000 lab animals at the Baylor College of Medicine drowned. “The city never came to help us,” Scott recalled. Life-saving evacuations were made possible by National Guard Blackhawk helicopters.

After Allison, working with city, county, and FEMA, the TMC shifted its long-term planning focus. Master Plan Report 2001: Hazard Mitigation for the Institutions of the Texas Medical Center (2002), and Vision for Strategic Growth 50-Year Plan (2006), detail the TMC’s joint efforts with FEMA, city, and county to widen Brays Bayou south of the TMC, and build a series of new storm sewers and retention reservoirs. The federal government carried about 90 percent of the cost of a series of multi-million dollar projects.

When Hurricane Harvey hit in 2017, the TMC was prepared. The hospitals remained in operation, and likely many lives were saved. But the TMC’s efforts, if government funded, had not extended past its nonprofit property lines. Brays Bayou was supposed to be widened west of the campus too, through the Meyerland neighborhood, but it had not been (a large retention pond that failed was built instead). Arguably, and there is much argument, the focus on the TMC was one reason why Meyerland flooded so badly. Just down the bayou, Meyerland is a neighborhood that is home to many employees of the TMC. The TMC could only govern itself, not the city.

| « Bellaire v Baytown Lee | Cy Twombly Gallery » |