Should Houston Exist?

While I was working on this project, in September 2019 Tropical Storm Imelda struck Houston and some parts of the city disastrously flooded again.

There are two responses to climate change that appear to be polar opposites of one another, but in fact lead to very much the same result. One response, familiar to Houston, is denial, or the idea that climate change may well be nothing but a “hoax” of a ruling and jet setting global elite, who all, making it even worse, are the ones who have benefited most from the economic growth that is said to have resulted from human-induced global warming.

Another is the apocalyptic response. It is too late. If the world will not simply burst into a ball of flames, awful catastrophes loom. This is not a belief one hears espoused so much in Houston, a city premised on fossil fuels, but also one that still pictures a bright future always in front of it. But the apocalyptic response is a framework in which it makes sense to answer the question – Should Houston Exist? – with a resounding no. The city exists because fossil fuels still power the global economy. Since about 1980 (my lifespan), about the time when the scientific confirmation of manmade climate change first settled, greater Houston has doubled in size, adding nearly four million people to its pattern of high-energy consumption, automobile and air conditioning based urban sprawl. If it was possible to go back in time and halt, if not prevent this from happening, given what we know about the extreme risk of loss associated with climate change, would we not?

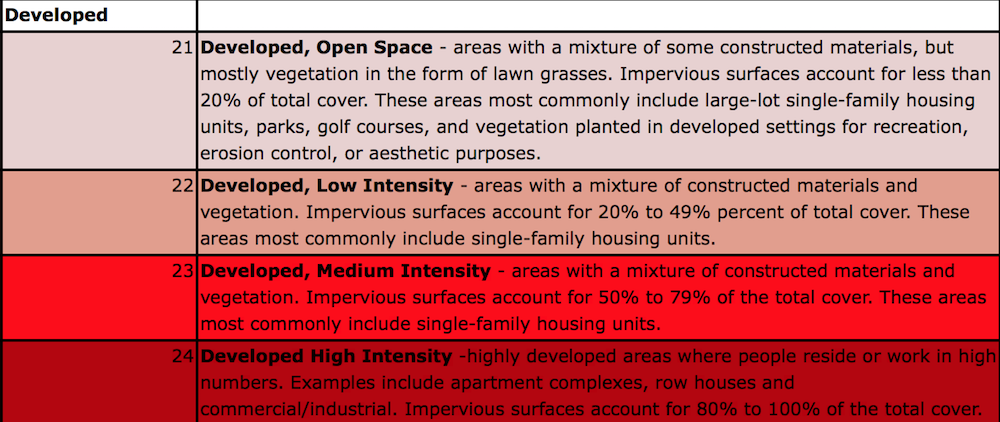

I’m particularly struck by what was done, was not done, or could have been done, during the period between Tropical Storm Allison (2001) and Hurricane Harvey (2017). In Harris County, between 1996 and 2011 surfaces impervious to water increased by a quarter. From 1992 through 2010, the region lost about a third of its wetlands, or 16,000 acres. Northwest of Houston, outside of Harris County, one of the most intensive areas of recent development, three quarters of the 600,000 acre Katy Prairie has been paved over, and no longer absorbs rain water. As late as 2016, Mike Talbott, the longtime head of the Harris County Flood Control District, bragged about having no plans to study the impact of climate change on Harris County, criticizing scientists for being “anti-development.” “They have an agenda,” he said, and “their agenda to protect the environment overrides common sense.” In the 2001 flood, the county’s floodplain maps, having not taken into account the way development constantly reshapes the floodplain, only predicted half of where the flooding occurred. Redrawn, in the 2017 flood the county’s floodplain maps, still only predicted half of where the flooding occurred.

But Houston was built, keeps being built, and will continue to grow. As a Houstonian, that makes me happy. I love the city. During its more recent phase of growth it has been become a far more diverse and interesting place. Its convivial sociality, born of the willingness of Houston’s residents to appropriate commercial spaces and interactions for noncommercial purposes (translation: you can have genuinely warm conversations with people in line at the grocery store), is another of its greatest qualities. Expectant of spectacular future growth, it also has, even in dark times, a bright outlook.

Should Houston exist? It does, and it will. Unlike many false press reports in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, Houston is not a city destined to perish or even fundamentally change as we know it if even modest projections of global warming come true. Houston is not Miami. It sits amidst bayous, but it also sits some 50 feet above sea level. There will be more floods, as rainfall increases, perhaps leading to more loss, including of life. But the city will not wash away, not at least anytime soon.

Where deniers and catastrophizers however seemingly radically opposed are in agreement is on one subject: what to do. Either motivated by credulity or despair, both would do nothing. But there is another way to think about the problem. For the era that saw Houston’s rise – the era of does climate change exist, will it happen? – has closed. Prediction, prevention, mitigation are still urgent matters, and will remain so, but living with climate change is now a distinct problem of its own. How will Houstonians, who aren’t going anywhere, live with climate change?

Houston’s growth should slow down. There should be an “urban growth boundary,” as there is in many cities, most successfully in London. This will require a supra-county effort. What is left of the Katie Prairie should be preserved. If the pace of growth slowed down because oil becomes less central to the global economy, as non-carbon emitting supplies of energy emerge, all the better, and perhaps Houston’s engineering community could commit itself to that project, as opposed to developing the technologies behind deep water drilling and fracking.

Further, regardless of the overall pace of growth, the city will have to do more to shape its direction. It will have to engage in long-term urban planning.

Here, there is to consider Plan Houston (2015), the first “General Plan” of the city of Houston in its history. Published on the eve of the 2015-2017 flood cycle, which culminated in Harvey, Plan Houston is, for lack of a better description, a pitiful document. There is not one map. It consists of, mostly, self-celebrations, as well as anodyne and boilerplate pronouncements. “Houston offers opportunity for all. We celebrate our diversity…” That is not urban planning. Incredibly, and tragically given the storms soon to come, it makes no mention of climate change, and no mention of flooding, whatsoever. Plan Houston’s greatest theme is need for the city to “Partner with others, public and private,” to “coordinate with partners,” to “expand partnerships,” to “partner with organizations,” to “support partnerships,” to “coordinate with partner organizations,” and to “work with external organizations,” especially with nonprofit corporations, although towards what end it is not exactly clear.

There is one nonprofit that has illustrated a forward-looking capacity to plan, and that is the Texas Medical Center. But it only controls and looks out for the property it owns. That is the limit so far in Houston.

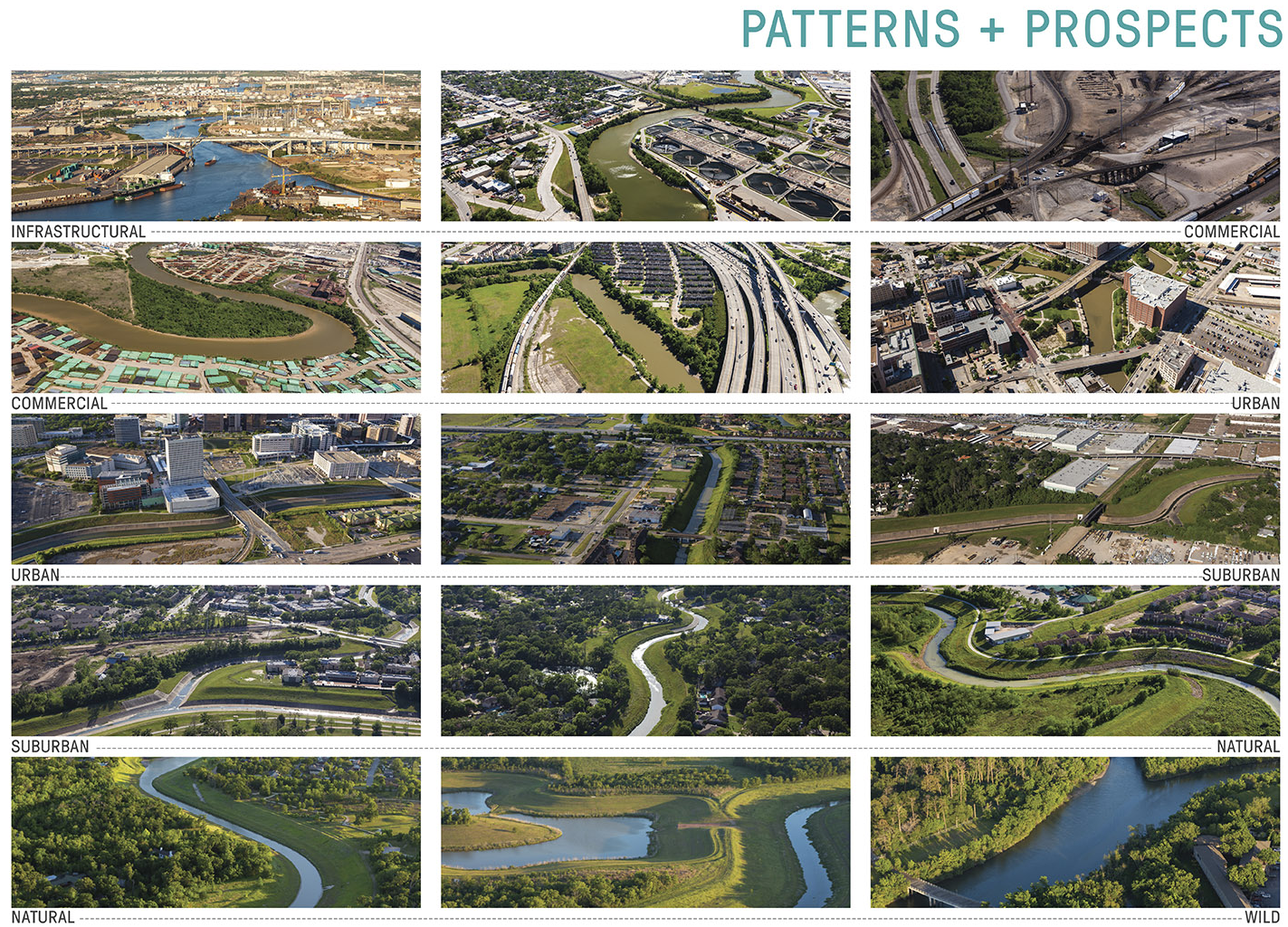

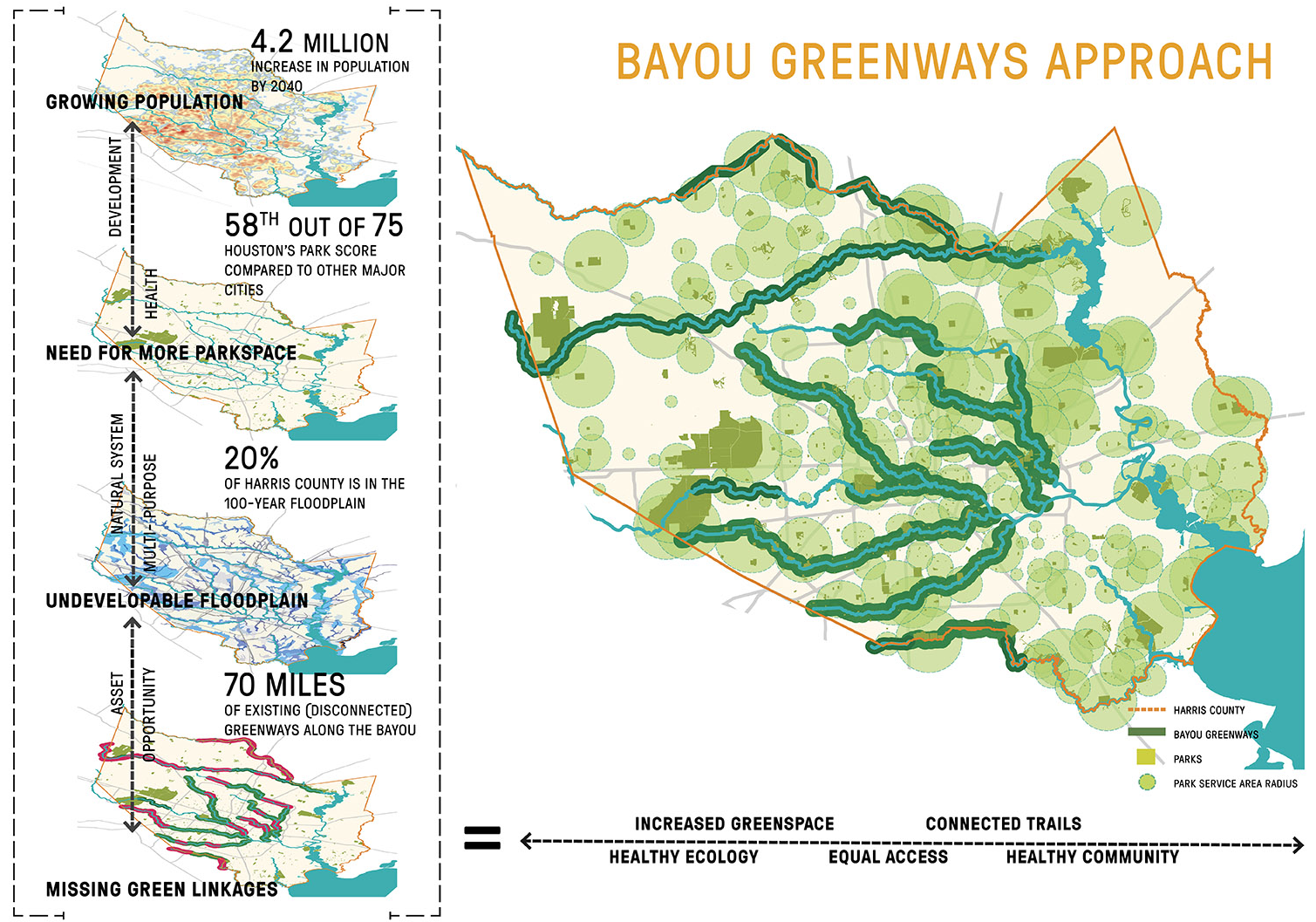

In this context, the most promising document I have yet to come across is Bayou Greenways 2020. This is another nonprofit corporation, the Houston Parks Board, which donates money, time, and expertise to the city of Houston to help in manage and develop its parks. Bayou Greenways is the first planning document, of any kind, that states, even if only implicitly, the obvious – that the city’s ecological traffic, the west to east water flows of the bayous, conflicts with the automobile traffic of the city’s highway system, as well as its polycentric pattern of development. Bayou Greenways 2020 does not call for more storm sewers and retention reservoirs to capture rainwater that the bayous cannot contain. Instead, it calls for bands of new green space hugging the bayous to connect, creating a single, overarching park.

City voters approved $100 million of funding for the project in 2012, and since then, in a classically Houston public-private partnership, another $120 million arrived from philanthropic sources.

The point is twofold. First, it is to create greater absorptive capacity for floods. Second, is to get Houstonians to think about differently, and see differently, the relationship between city and ecology. The city cannot see its ecological habitat as something distant and independent from its pattern of development – a “nature,” either to mitigate, control, or perhaps ignore. It must, in the phrase of Rice University philosopher Timothy Morton, have the “ecological thought,” the recognition that all forms of life are connected in a “vast, entangling mesh.” Development should proceed from there.

Since Hurricane Harvey, however, Bayou Greenways 2020 has become the template and inspiration for a far more radical proposal: Houston should carry out a “tactical retreat,” as the Rice architectural critic Albert Pope has put it, from the 100-year floodplain all together.

Since Hurricane Harvey, however, Bayou Greenways 2020 has become the template and inspiration for a far more radical proposal: Houston should carry out a “tactical retreat,” as the Rice architectural critic Albert Pope has put it, from the 100-year floodplain all together.

After all, the neighborhoods that align the bayous are for the most part continuous with the 100-year floodplain. There are 10,000 structures in Houston’s 100-year floodplain, taking up the space of a mid-sized US city. John Jacob, the scientific director of the Texas Coastal Watershed Program, who too has called for abandoning the floodplain, admits, “It would be traumatic. It’s not something that should be taken quickly. But it ought to be a goal.” The city would have to take private property from its owners, violating what has been the city’s most elemental urban form. In one study, the project would require buying up 30,000 acres. To reverse the engineering that turned the bayous into the concrete storm sewers would mean digging up 8.7 billion cubic feet of earth. The total estimated cost of the whole project is $27 billion.

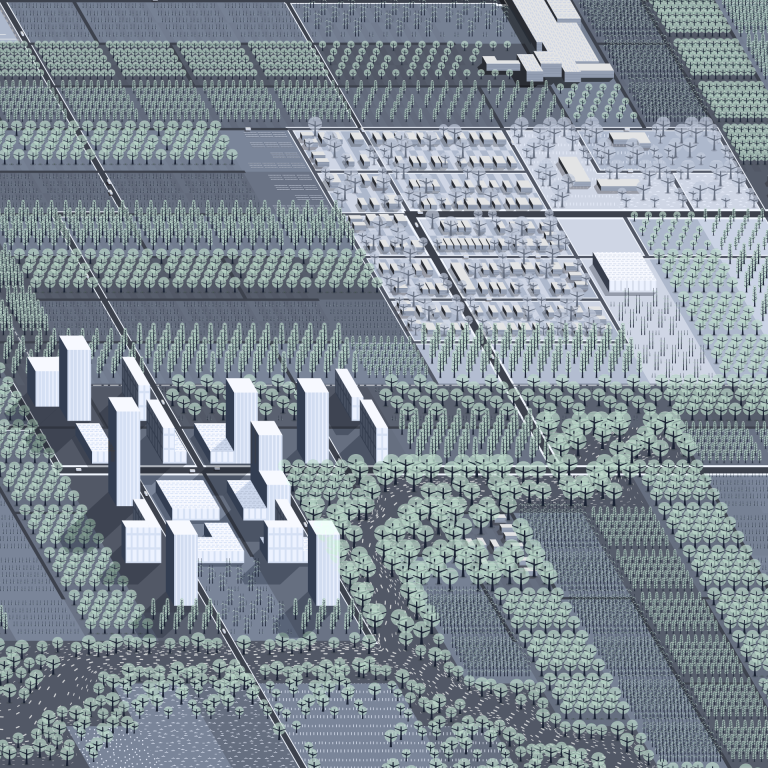

It could be done. But it would only work if it were part of a more general exercise of public authority, part of a general plan – that explained how and why the city would continue to exist and grow, if no longer in the same way as the past. Abandoning the floodplain and reorienting the city around the natural flows of the bayous would inevitably mean more density, less automobile use and traffic, accelerating trends, in fact, already underway in the city. Houston in recent years has had the highest number of multi-family housing starts in any US city.

|

|

This project could not possibly be imagined, let alone carried out, by a governing authority so split up among different entities, whether it is federal, state, county, or city, or the thousands of nonprofit corporations that govern Houston on a day to day basis. To find the politics necessary to guide Houston to expropriating 100,000 homes and to reconstruct the city's infrastructural basis nearly from scratch would seem impossible. But on the planetary scale, much more dramatic and improbable efforts than this will likely be required. If you have no politics for what to do with Houston, that is, then you have no politics for what to do about global warming.

As for the abandonment of Houston’s floodplain, among the neighborhoods that would surely be eliminated – with single-family homes, roads, gas stations, schools, churches, strip malls, baseball diamonds, and a Jewish Community Center becoming parks, trails, gullies, and bike paths – would be the neighborhood I grew up in, Meyerland. It would have to go. The question “Should Houston Exist?” comes back around, except now in the form to me of “Should My Houston Be Allowed to Stand?” Unlike many of my friends, who still work and live in the neighborhood (one of my closer friends is even a homebuilder), I no longer live in the city, let alone the old neighborhood. The question has a different set of stakes for me than it does for them. At all events, in the new era of living with climate change, planning for the future is very likely to be inseparable from mourning loss. If not, surely an even greater loss looms.

| « Cy Twombly Gallery |