Transco Tower (1982)

Gerald D. Hines was born in 1925 in one of the great American steel towns, Gary, Indiana. He moved to Houston in 1948, in advance of the larger Midwestern rustbelt migration to the city that peaked during the 1970s, but still continues. Hines graduated with an engineering degree, but in Houston he would create a commercial real estate empire. Today, Hines Interests is among the largest privately held real estate firms in the world. Most of its new projects appear to be in China.

Hines first became known as the builder of low-slung modernist commercial office buildings along the city’s Richmond Avenue corridor.

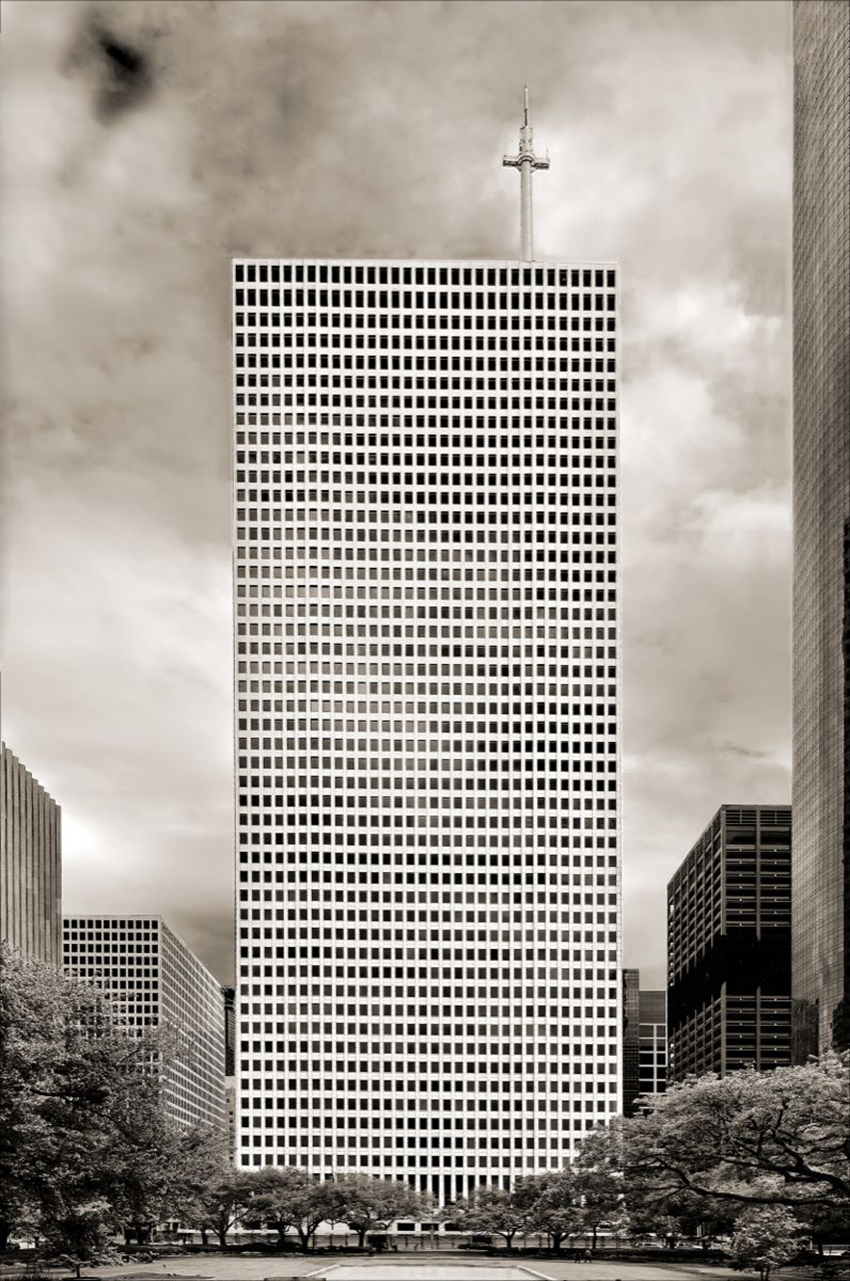

Then, he turned to skyscraper construction. The big break came in 1967, when Royal Dutch Shell hired the firm to construct twin skyscrapers upon the transfer of its US headquarters from New York City to Houston.

Then, he turned to skyscraper construction. The big break came in 1967, when Royal Dutch Shell hired the firm to construct twin skyscrapers upon the transfer of its US headquarters from New York City to Houston.

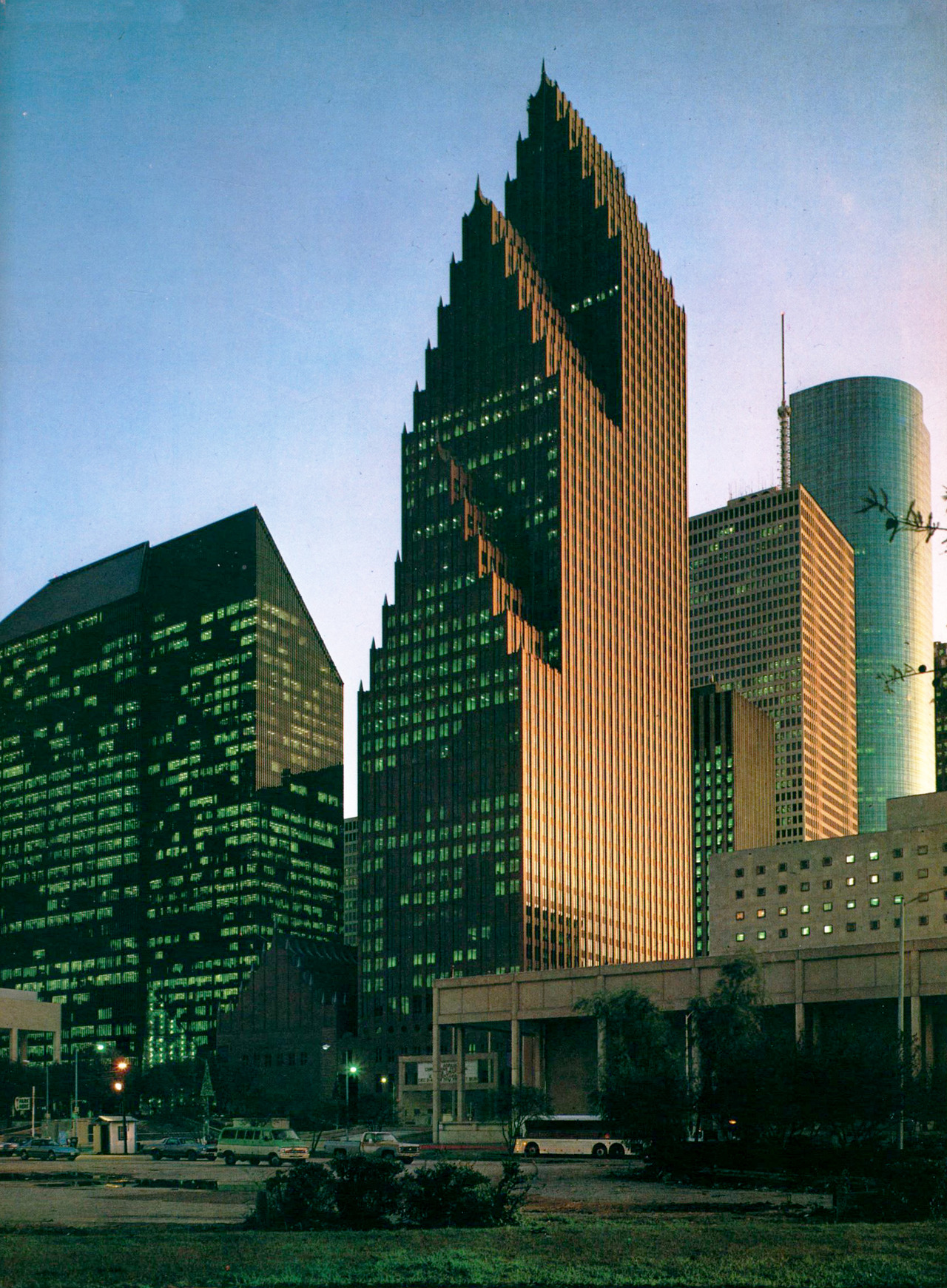

Hines’s most important downtown skyscrapers, Pennzoil Place and Republic Bank Center, co-designed by the noted architect Philip Johnson, were completed in 1975 and 1987 respectively.

Hines developed yet another Johnson co-designed skyscraper in 1982, Transco Tower (today, it is Williams Tower).

Transco was not built in downtown, however. It is in west Houston, adjacent to another Hines development, the indoor Galleria shopping mall (1970), which is located at the confluence of three freeways, I-10, I-69, and the 610 Loop.

It has become, over the years, one of the city’s many polycentric nodes, now called uptown.

Of these, Pennzoil Place is by far the most architecturally significant building. Pennzoil features a two tower trapezoidal design. Its optics split the “glass box” design of modernism, marking an architectural departure into a new, disorientating “post” – whether postmodern, postindustrial, post-Fordist – era.

Of these, Pennzoil Place is by far the most architecturally significant building. Pennzoil features a two tower trapezoidal design. Its optics split the “glass box” design of modernism, marking an architectural departure into a new, disorientating “post” – whether postmodern, postindustrial, post-Fordist – era.

To a child, however, Transco stood out far more. As the “tallest building ever built outside of a downtown,” it was impossible to lose sight of it driving around the west side of the city. It was a 1980s individual, having broken out from the mass of downtown. In a driving, not walking city Transco offered visual orientation, a fixed point in a city in a constant state of development and growth. Transco also had a small, one-city block park nearby with a water fountain, also designed by Johnson, which was next door to my grandmother’s retirement home.

To a child, however, Transco stood out far more. As the “tallest building ever built outside of a downtown,” it was impossible to lose sight of it driving around the west side of the city. It was a 1980s individual, having broken out from the mass of downtown. In a driving, not walking city Transco offered visual orientation, a fixed point in a city in a constant state of development and growth. Transco also had a small, one-city block park nearby with a water fountain, also designed by Johnson, which was next door to my grandmother’s retirement home.

This park was always eerily empty. There are large city parks in Houston, but they stand somewhat apart from the city. There have been few green spaces that are integrated into the communities where people live. The water fountain still stands, but since the 1980s the lots around Transco have slowly been filled up by more development.

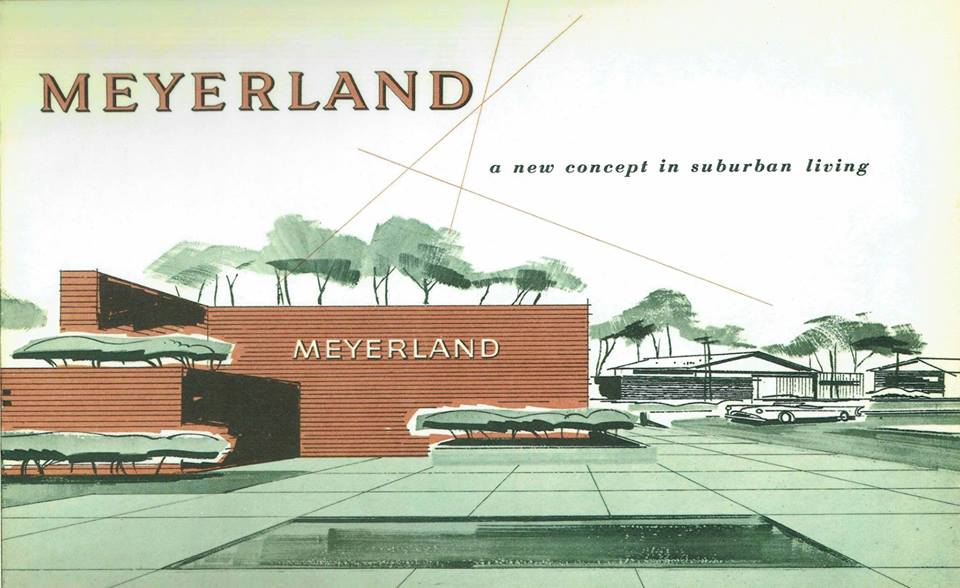

I would like to do research in the records of Hines Interests, since, if there was any foresight or intelligence behind the larger pattern of Houston’s development, it is more likely to be found there, or in the records of the major oil corporations and other real estate firms who were the “master planners” of so many residential subdivisions, such as Meyerland, rather than in the city’s own records.

I would like to do research in the records of Hines Interests, since, if there was any foresight or intelligence behind the larger pattern of Houston’s development, it is more likely to be found there, or in the records of the major oil corporations and other real estate firms who were the “master planners” of so many residential subdivisions, such as Meyerland, rather than in the city’s own records.

But the archive of the Architecture & Planning Research Collection at the Gerald D. Hines School of Architecture at the University of Houston only possesses photographs from a 2007 50-year retrospective exhibition on the firm. Not much else is available to the public.

Nonetheless, it is possible to trace the kind of social and economic development that Hines promoted, however wittingly. Houston’s east side has a large petrochemical complex. But accounting for much more of Houston’s economic growth than in the industrial cities of the past was real estate.

Developers like Hines gave the city of Houston a layout of space. In an industrial city – like Gary, Indiana, the kind Hines grew up in – there were factory communities. Little societies formed around the factories, whose raw economic output, over time, produced money incomes, whether they flowed to the owners and managers of the factories in the form of profits and salaries, or to their workers, many of them male breadwinners, in the form of wages. In Houston, the production of economic value orients more so around space, rather than time. Rather than forward planning, movement across space yields the future. Led by private developers, the city sprawls. Nodes pop up, sometimes as if over night. Hines was largely responsible for the eight-mile stretch connecting downtown to uptown. Density and economic activity arose in the wake of the firm’s developments.

In an economic pattern of development so dependent upon real estate, much income flows to property owners, not labor. That is one reason why income inequality in the US has so dramatically increased since 1980, and also why economic productivity and growth, typically the results of investments in production, have disappointed since then, too. It is because the progress of Houston, and cities like it, account for so much of US economic growth since 1980.

In an economic pattern of development so dependent upon real estate, much income flows to property owners, not labor. That is one reason why income inequality in the US has so dramatically increased since 1980, and also why economic productivity and growth, typically the results of investments in production, have disappointed since then, too. It is because the progress of Houston, and cities like it, account for so much of US economic growth since 1980.

And yet, one reason why the US has remained a more dynamic economy in the past decades, compared to, say, much of Europe, is because of the vigor of cities like Houston. It flows from the service industries, including real estate, but of course also “oilfield services,” a global operation for Houston-based firms, spanning oceans. At the top of the Houston income distribution, there are, say, commercial real estate developers like Gerald Hines. Their property incomes create employment demand for, say, therapists and personal trainers, as well as real estate lawyers and appraisers, whose incomes create demand for, say, retail service employees, who worked in the uptown Galleria shopping district, near Transco. At Transco, there is demand for security guards and janitors. At the nursing home across the street, there are food service workers and nurses, lower-income occupations, typically feminized, that have been dominated not by migrants from the Midwest and Northeast in flight from deindustrialization but rather from Mexico and especially during the 1980s Central America, as well as from the city’s black population. As for social life, communities form not around factories, but around other hubs and magnets, related to services – shopping malls, hospitals, churches.

The built environment of the city of Houston shifted rapidly during the second third of the twentieth century, as developers like Hines built the city out. They had plans of their own, if no larger plan guided their efforts.

| « Zoning Referendum III | National Women's Conference » |