Photo Captions

Power Grabs and Crude Decisions

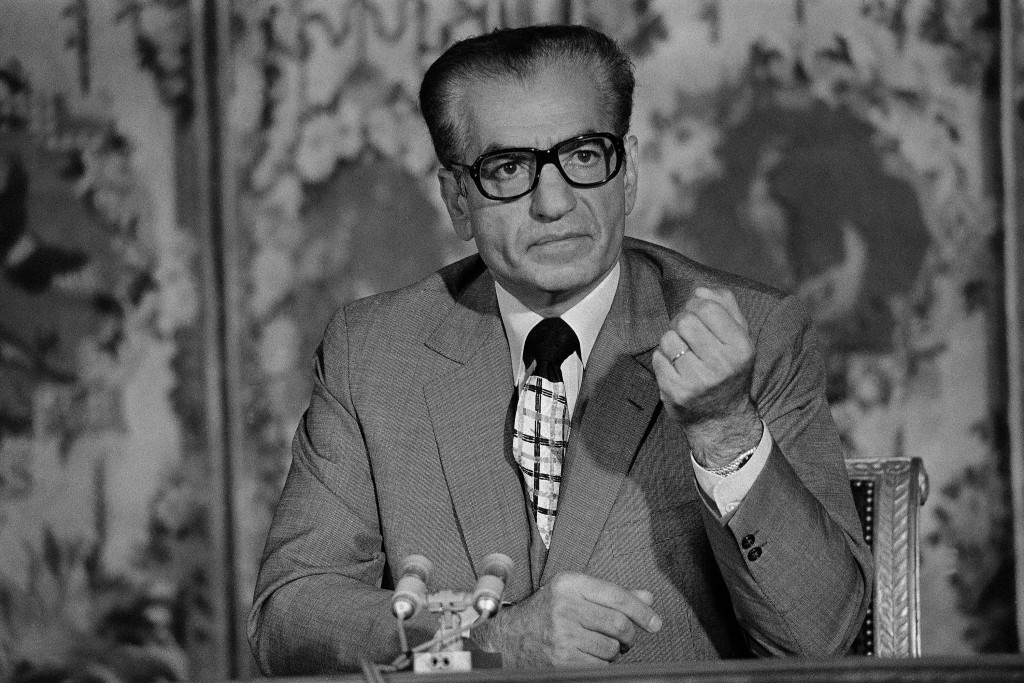

This photograph was taken on June 27, 1974, in Versailles, France, at a press conference held by the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Eighteen months earlier, the Shah had re-nationalized the oil operations of French, British, and American companies in Iran in a bitter dispute over production levels and revenues owed to the Iranian treasury. Yet here he was in Versailles, accompanied by fireworks and a full-blown Royal welcome, inking a $1 billion deal as advance payment for shipping Iranian oil to France.

The Shah’s forced takeover of foreign oil company operations exemplified a global trend among oil producers, ranging from oil nationalizations in Syria in 1968 and Algeria in 1969, to Peru in 1973 and Angola in 1978. In total, over one-quarter of all major oil-producing countries nationalized their petroleum sectors between 1968 and 1978.

The conventional wisdom is that expropriations in this era were driven either by nationalistic fervor to expel the last vestiges of foreign imperialism or by the lack of domestic political constraints on overzealous rulers. Yet the archival record paints a different picture. As I demonstrate in my book, Power Grab: Political Survival through Extractive Resource Nationalization, documents from the British Petroleum archives and the Shah’s personal correspondences – coupled with case studies of Saudi Arabia and Iraq, and statistical analysis of 60 other oil-producing countries – illustrate perceptions of political survival as a key component of the decision calculus to nationalize.

By taking control of the means of production, leaders capture revenues that might otherwise flow to private firms and use this increased capital to secure political support. But nationalization is ultimately a gamble: immediate windfalls come at the risk of future production losses and international retaliation (something to which Iran was no stranger). For those whose days in power may be numbered – politically insecure oil-rich leaders – nationalization is a risk worth taking. But for those who foresee long, lasting rule – strong oil-rich leaders – the returns may be too costly.

Three and a half years prior to this photograph being taken, the Shah held a rosy outlook on his future rule. He had agreed in January 1971 not to nationalize the oil industry and instead struck a deal with BP and Royal Dutch Shell. In the midst of negotiations, the Shah boasted that the agreement would be successfully implemented – but only if, in his words, “there is no discrimination, no favoritism, and no dirty tricks on the part of the company negotiators.”

BP and its partners didn’t live up to the bargain. The Shah – who had grown more insecure about his time in power – nationalized oil after discovering the companies had secretly offered better terms to his Arab neighbors and had been underpaying the Iranian government. Fifty years later, the oil companies’ misdeeds live on, distorting climate science and misleading shareholders. Now, however, the costs of these “dirty tricks” are not just borne by citizens and governments of oil-producing countries – they imperil the entire planet.

Paasha Mahdavi

@paashamahdavi