Photo Captions

Suburban Borders

Photo Album, The Roland Park-Guilford District, Box 294, Roland Park Company records, MS 504, Special Collections, The Johns Hopkins University

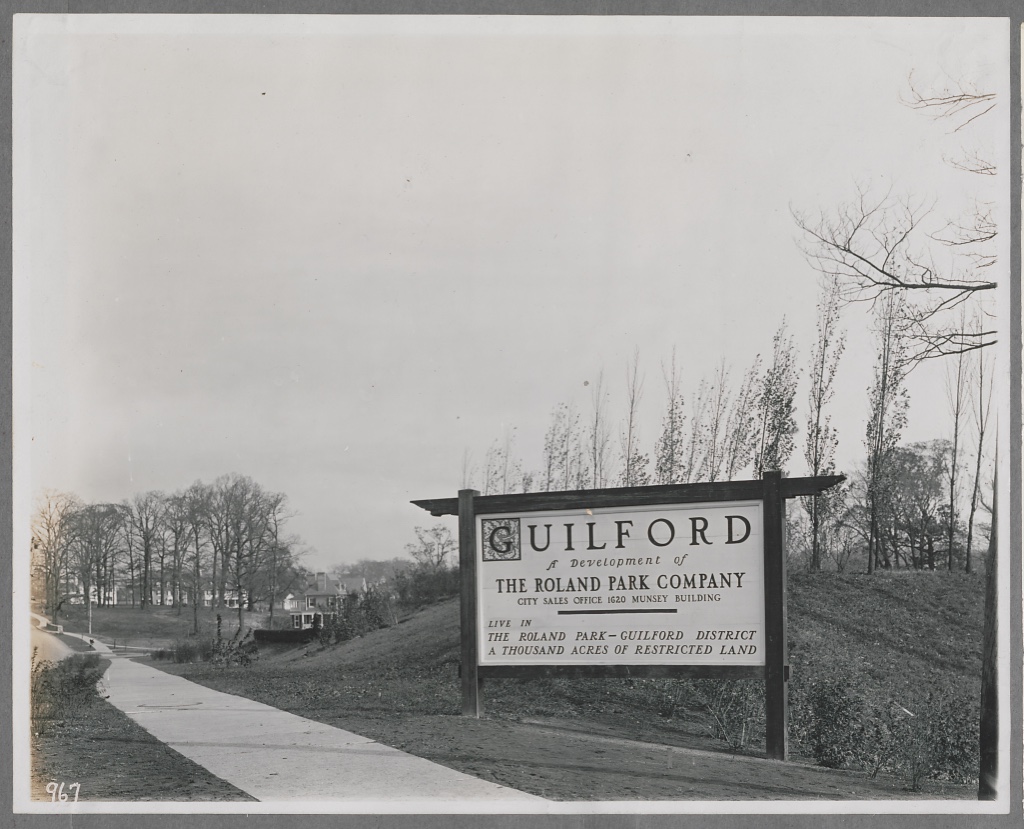

The image shows a sign for the community of Guilford, a residential neighborhood that opened in Baltimore, Maryland in 1913. It was the second development of the Roland Park Company, whose eponymous suburb was the area's first planned, segregated subdivision. The "restricted land" on the sign refers to the set of legally binding rules that homeowners followed when they signed the deed for their house. These included minimum home costs, the appearance of a property, acceptable uses, and perhaps most importantly, a restriction against blacks from occupying any property unless they were domestic servants.

Restrictions only constituted one tool the Roland Park Company used to assure buyers of long-term health, wealth, and stability. Along its borders, the company used a series of visual strategies to separate Guilford from surrounding working class, mixed race neighborhoods. It created one-way streets leading out, disconnected from the existing grid. Single-family homes faced inward toward Guilford or were set back far from the street, separated from the adjacent community by a fourteen-foot high wall. Company officials explained these tactics as protecting Guilford from "eyesores" like the rowhouses and commerce just outside its eastern edge, but their treatment of borders also served a social function. Just as the deed restrictions conflated race, class, and aesthetics, "eyesores" meant both buildings and people.

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, developers began to market planned communities on the peripheries of cities across the United States. These developers responded to what they saw as demand from affluent native-born whites who wanted to distance themselves from the incoming migrants and immigrants seeking industrial jobs. Block-by-block segregation already existed in many cities, but technology such as the street car and, later, the automobile, made it possible for developers to create entire neighborhoods from scratch. A core premise of suburban planning, then, became how to signal exclusion.

Guilford's borders attest to how the early tactics of residential segregation not only endure today but also continue to shape lives and landscapes. They serve as a reminder that a house has always been more than a place to live. In the United States, one's house is their main generator of personal and inherited wealth. A person's address impacts where they go to school, how they access credit, and where they work. It also shapes government services such as policing. With so many factors tied to place of residence, it is no wonder that where someone lives affects their very expectancy.

Many disparities between neighborhoods in health and wealth have roots in the ways policymakers endorsed the discriminatory practices of suburban developers pioneered by the Roland Park Company. Today, as in 1913, Guilford remains restricted land. A walk along its border is a study in stark and abrupt contrasts. It remains one of Baltimore's wealthiest, whitest neighborhoods.

Paige Glotzer