Photo Captions

Unruly Rememberings

It is either chance or upshot that the Sri Lankan State’s National Identity Card Project came at the heels of the nation’s first (unsuccessful) armed revolt instrumented by the Marxist-Leninist inspired Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (People’s Liberation Front) led by Rohana Wijeweera against the government helmed by Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike. Uncannily the 5th of April 1971 marked not only the beginning of the 1971 JVP insurrection that was violently quelled by the state over the ensuing months, but an expansion to the 1968 Registration of Persons Act to cover the issuance and use of National Identity Cards (NICs) to legal residents over the age of 18. In the year that followed, the island would further assert its independence as a modern state, shedding its dominion status and colonial name of Ceylon in favour of ‘Sri Lanka’.

Initially designed as a folding booklet to include a 2"x2" Rolleiflex photograph, the NIC was made compact by the introduction of 35mm film photographs by Dr. D.B. Nihalsinghe, the erstwhile director of the Government Film Unit (GFU). With the support of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) which donated a few thousand Praktica cameras and film, the state’s photographic documentation project was initiated, instituting both the standard size and aesthetic of what would become an essential portrait; 35mm x 45mm, right in semi-profile with the left ear fully visible as per official requirement – for many decades in black and white, but as of 2005 in colour.

In the early 1980s, Sri Lanka’s ethno/political tensions would heighten into two brutal conflicts that would irrevocably alter its socio-economic and political fabric; an armed struggle for an independent state in the Tamil majority North (1983-2009) that would intensify into a civil war, and a second JVP insurrection (1987-1989). The escalation of conflict would transform an already essential NIC into an indispensable extension of personhood; as proof of identity, as indication of ethnicity and location, and ultimately vital for Tamil citizens, in particular, in navigating and surviving the dense and repressive state security and surveillance apparatus during the war years and its aftermath.

In my ethnographic foray 1 into popular photographic practices in Northern Sri Lanka, older photographers recalled the distribution of cameras. However, for many the project also occasioned their first encounter with photography, thus becoming anointed as citizens. Given the relatively late arrival of cameras into the Sri Lankan household and the potentially prohibitive expense of a studio commission for many, the NIC photo would afford a new medium for picturing themselves; not merely as citizens surveyed by the state, but as individual whose image and memory might now endure in a capacity that may not have been possible before.

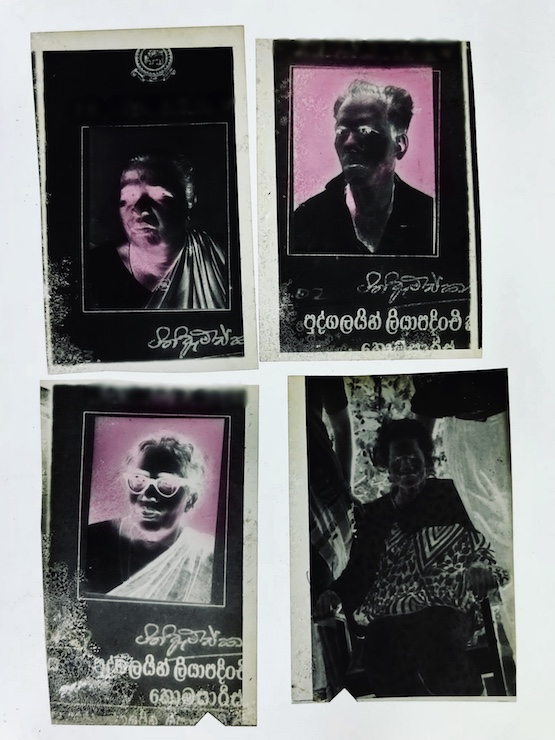

Among the sparse remains of Jaffna’s studio archives raggedly pared by decades of violence and displacement, fragments of re-photographed NICs, however, were a common sight. In a particularly tattered archive spanning the 1970s to the 2000s, ‘copying’ negatives as pictured above were common. As elderly subjects of the NIC project succumbed to age and the number of war deaths inclined, these copying images grew in number, especially where any other photographs of the deceased were unavailable – speaking to a tangle of circumstances rooted in war, displacements and household economics. Provided to the studio by loved ones to make memorial portraits, the studio would reprint these photographs for a small cost, and these images would then be used in the design and printing of death notices, or re-touched and framed to be placed in a position of reverence in the household. Delicate smears of red speak to forgotten technics of hand-retouching, before its potential passing on to a professional over-painter who would elevate the lowly identity photo into an extravagant keepsake. Indeed, the creation of memorial portraits remains a significant part of the business of Jaffna’s photography studios and frame shops, where the many splendored potentials of photoshop are now wielded to reinvigorate the memorial portrait into even more extravagant mementos, further garlanded with electric lights and plastic flowers.

The social appropriation of the NIC photograph and its vivid afterlives vexes the extant language and frequently binary theorisations of photography, where photography is either manoeuvred as a tool of surveillance by the state as proposed by John Tagg following Foucault, or its democratisation and emancipatory political potentials for resistance and solidarity in citizenship as suggested by Ariella Azoulay. However, what the afterlives of NIC photographs evoke is the unpredictability of the photographic image, re-cast to occupy the messy intersection of the state and the social. This invites us to consider the very unruliness of photography, in its multifaceted invention and reinvention by vernacular practitioners and the social worlds within which they exist and continue to transmute.

Even in these patchy copying negatives that comprise the decaying image detritus of old-fashioned studios that are falling out of fashion, we catch a glimpse of the extraordinary dynamism of the photographic medium and its inextricable entanglement with our everyday lives and own afterlives. These fragments remind us of the complex and unpredictable ways in we seek to position, frame and articulate our social selves by way of the photographic image. They invoke the aesthetic and cultural legacies of photography we draw from in our everyday rememberings and forgettings that comprise the intimate minutiae at the crossroads of our personal memories and national histories.

1 This research is a part of Photodemos: Citizens of Photography – The Camera and the Political Imagination at UCL Anthropology. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 695283. The image above may not be used or reproduced without the author's permission

Vindhya Buthpitiya