Photo Captions

Coping with Defeat: Indian posters of the 1962 Sino-Indian War

|

|

|

|

Images numbered clock-wise from top left to bottom right.

These images are copies from the Arunachal Department of Information and Public Relations (photograph collections for 1962, M 2625-2628). Every effort has been made to contact all the copyright-holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the author and organizers of Invisible Histories will be pleased to make the necessary arrangement at the earliest opportunity.

Four images, four administrative efforts to cope with a brutal military defeat. The posters you see here were produced by Indian authorities administering a frontier region called the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) after the Sino-Indian War of 1962.

In October 1962, after years of deteriorating bilateral relations and failed boundary negotiations, China invaded its Indian neighbour. For one month, war raged on in the Himalayas. The conflict ended in a military rout for India. China almost reached the Indian plains, and while it eventually withdrew from NEFA for complex reasons, it consolidated its hold over another strategic chunk of the Himalayas, the Aksai Chin.

Individually and collectively, these four posters painted in the immediate aftermath of the Sino-Indian War represent the beleaguered Indian authorities’ attempts to shape the historical memory of the conflict, and in doing so to protect their position vis-à-vis Indian public opinion and local Himalayan inhabitants.

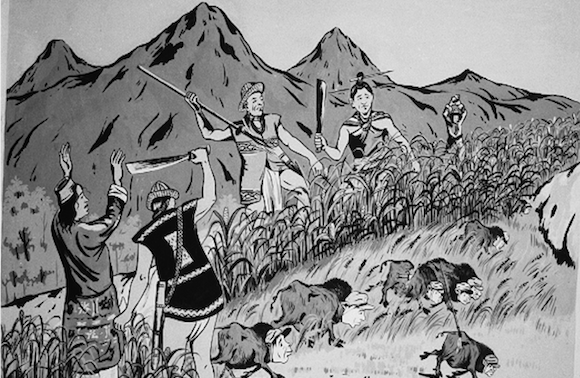

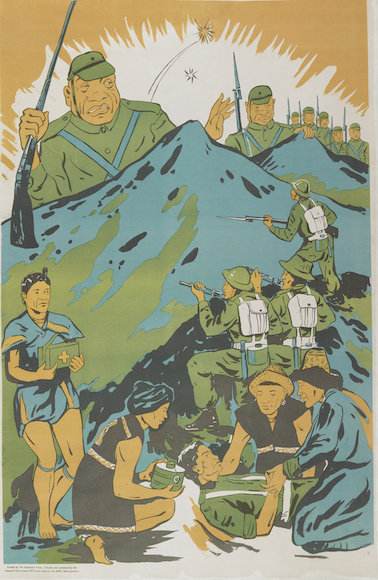

Each poster encapsulates a scene evoking the war. In Picture 1, five NEFA inhabitants chase away a group of beasts with the body of a bison and the heads of Chinese soldiers. In Picture 2, the Chinese are represented in human form, appearing ominously over the crest of the Himalayas. A group of jawans (Indian soldiers) are ready to repel them, while in the foreground four inhabitants tend to a wounded soldier. In Picture 3, the Chinese invaders are still there on the horizon, but this time the focus is on a sari-clad Indian woman, looking anxiously at them while hugging a group of NEFA children close to her. Picture 4 conversely shows no trace of the Chinese, but the war is still there implicitly. Eight men—four NEFA inhabitants and four civilian and military representatives—hold hands, smiling straight ahead while Indian flags flutter over their heads.

What is striking about these posters is that the focus of attention is not on the fighting, nor even so much on the enemy, but on the relationship between the inhabitants of NEFA and the Indian state’s representatives—a relationship represented as defined by empathy, solidarity and patriotism. Each poster delineates one facet of that relationship. In Picture 1, NEFA inhabitants chase the Chinese beasts on their own, repelling the invader with an instinctive patriotism. In Picture 2, it is Indian jawans (back then drawn from outside NEFA) who fight the Chinese, but the inhabitants are there to rescue the wounded. In Picture 3, the inhabitants are represented as children, sheltering under Mother India’s protective embrace. In the final poster jawans, civilian officials, and Himalayan inhabitants re-affirm their unity in the service of the nation.

Now look at subtler visual details—they offer additional clues to interpret the posters’ meaning. Clothing is particularly important. Even beast-like, Chinese soldiers are immediately recognisable by their hat, worn in the People’s Liberation Army. Do you notice how each NEFA inhabitant wears a different dress-style? For the general viewer, it underscores the region’s ethnic and cultural diversity, and its distinctiveness within India. A more familiar eye immediately recognises the “typical dress” of several prominent local tribes: the Monpa with his thick coat and Tibetan fur hat; the Nyishi with his knotted hair-bun, high on the forehead; the Adi with his short, embroidered cardigan and cane hat; or the Mishmi with his wide, striped collar and coiled hat. Back in 1962, it is unlikely they would have had an occasion to fight the Chinese together. The Mishmis lived hundreds of miles away from the Monpas. Placing them within the same frame sends a powerful signal that all NEFA was involved in the fight. Small dress-related details are again important in Picture 4. Beside the doctor, the other civilian official wears a suit and, significantly, an Adi jacket over it. This detail matches actual administrative directives asking NEFA staff to wear Himalayan clothing to signify their empathy and symbiosis with the inhabitants, and is used precisely to that effect in the poster. Picture 3 has perhaps the most archetypal feel of all. The sari-clad woman clearly represents Mother India, one of the key representations of the nation, caring for her children in their hour of need.

All this hints that the posters were meant to convey a powerful message of courage, resilience, fraternity, patriotism, duty, and of unity-in-diversity (India’s patriotic motto). One is never left in doubt as to whom the enemy, the “Other” is. The lines are clearly drawn: the Chinese on the one hand, the “Indians”—whether civilian officials, soldiers, or NEFA inhabitants—on the other. Service to the nation in its time of crisis is self-evident, united, resolute.

What we have here are four startling examples of history-writing through pictures. Made by a government artist just after the war, perhaps in the midst of the Chinese occupation (October 1962-January 1963)1 these posters offer a vivid sign of the turmoil the NEFA administration found itself in as a result of the conflict, and how it sought to recover initiative afterwards.

The defeat had been disastrous. So disastrous that, even today, the 1962 War scars India’s collective memory. (One of the most famous Indian patriotic songs is in fact about the conflict.) In the weeks and months after the cease-fire, a furious debate erupted around the war, with powerful consequences for how it would be remembered. Public opinion sought people to blame for the catastrophe. NEFA’s civilian administration was singled out as bearing special responsibility. Its leaders were accused of having neglected the region, kept its inhabitants aloof and culturally separate from the rest of India, and woefully impeded its defence. As for NEFA’s inhabitants (the Adis, the Monpas or the Nyishis represented in these posters, but also others), some praised their anti-Chinese fervour and resilience in the face of adversity, but they were more commonly suspected of harbouring a preference for the Chinese enemy, if not of actively helping it.

Within NEFA itself, the war had been an electroshock. Even in areas that had not been invaded, Indian’s civilian administration had often collapsed. What’s more, the Chinese occupation had been relatively uneventful for the inhabitants. PLA soldiers had treated them well and tried to convince people they were there to “liberate them” from the Indians. When frontier officials moved back in after the PLA’s departure, inhabitants had welcomed their return only conditionally, and with strong demands that they be better served in the future. Rebuilding trust was essential.

These posters should therefore be “read” in a post-war context where the NEFA administration was desperately trying to justify itself to both pan-Indian audiences and to the inhabitants of the Himalayan regions that had been invaded. One quality of images is that they can be interpreted differently depending on one’s position and background. This quality is clearly at play here. The archival record does not tell us where the posters were circulated, but they clearly could resonate with different audiences. For NEFA’s inhabitants, these posters paint a positive picture of their participation in the war, while insisting on the unity and strength of their relationship to the Indian army and administration—at a time when many people felt anxious about militarisation and let down by civilian officials. The picture of Mother India protecting her Himalayan children particularly stands out in this regard. Meanwhile the posters sought to persuade pan-Indian opinion of the fundamental patriotism and efficiency of both frontier administration and Himalayan inhabitants, and of their united and courageous opposition to the Chinese.

There is much that remains obscure about these posters. Beyond the question of their audience and dissemination, it is unclear whether they belong to an official series or followed a specific sequence that would craft a complete historical narrative of the war. Nor does the archival context (the posters belong to government archives and to the private collection of a prominent NEFA official of the time) tell us much about a crucial issue: their reception among their intended audiences. Collective memories of 1962 are still contested. While the inhabitants of NEFA (now called Arunachal Pradesh) are now often presented as the most proud of Indians, the NEFA period is still remembered—incorrectly, I argue—as a period of woeful neglect that paved the way for defeat. On that count, these posters do not seem to have succeeded.

For me, the pictures hold yet an additional resonance. In my book, Shadow States: India, China and the Himalayas, 1910-62,I argue that the voluminous literature on Sino-Indian relations treats the Himalayas’ inhabitants as a footnote at best, when their presence and agency is in fact central to the roots of tensions between the two biggest countries in the world. These posters, so clearly focused on the relationship between Indian authorities and local people, with the Chinese in the background, serve as a stark reminder of their importance.

1 It is impossible to know for sure. The Arunachal Pradesh DIPR collections where I found them include them in the “1962” batch, but given the short length of the war and the extreme disorganisation of the civilian administration as a result of the conflict, it is unlikely they could have been commissioned until after the ceasefire, in late 1962. Given the time needed to sketch and paint this type of poster, early 1963 seems a likelier publication date.

Bérénice Guyot-Réchard