Birchbark Letters in Kyivan Rus’

This project concerns 762 birchbark letters from several cities (goroda/horoda) in Kyivan Rus’ dating between c.1100 and 1300. Kyivan Rus’ was a loose federation of medieval East Slavic principalities, comprised of the lands of modern western Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Starting in the 9th century, Rus’ expanded to include thirteen semi-independent principalities: Kyiv, Novgorod, Rostov-Suzdal’ (later Vladimir-Suzdal’), Ryazan, Smolensk, Polatsk, Turaŭ, Murom, Siveria (or Sivershchyna), Chernihiv, Pereiaslav, Volyn’, and Halyts. Overseen by the Velykyy Knyazʹ (Grand Prince) of Kyiv, the Rus’ lasted until the Mongols sacked Kyiv in 1240.

BIRCHBARK LETTERS

Birchbark letters are documents of personal, religious, business, and administrative content written on birch bark (known as gramoty na bereste) with styluses. Compared to parchment, which was expensive and used for liturgical books, “high” literature, and legal texts, and paper, which was first imported into Rus’ in the fourteenth-century, birch bark was free and widely available. Most of these letters are written in Old East Slavic, and the Old Novgorodian dialect with its distinct orthographical features. However, fifty-six letters are written in other languages: Old Church Slavonic, Greek, Latin, Low German, and Proto-Baltic-Finnish. Owing to the fragility of birch bark, many of these letters require linguistic reconstruction.

Birchbark letters are documents of personal, religious, business, and administrative content written on birch bark (known as gramoty na bereste) with styluses. Compared to parchment, which was expensive and used for liturgical books, “high” literature, and legal texts, and paper, which was first imported into Rus’ in the fourteenth-century, birch bark was free and widely available. Most of these letters are written in Old East Slavic, and the Old Novgorodian dialect with its distinct orthographical features. However, fifty-six letters are written in other languages: Old Church Slavonic, Greek, Latin, Low German, and Proto-Baltic-Finnish. Owing to the fragility of birch bark, many of these letters require linguistic reconstruction.

The first birchbark letter was discovered in Veliky Novgorod, in north-west Russia, in 1951 by Nina Fedorovna Akulova during archaeological excavations. As of February 2022, 1214 complete letters from the period between c.1020—1500 have been discovered in twelve Rus’ian cities: Viciebsk, Vologda, Zvenyhorod, Moscow, Mscislaŭ, Veliky Novgorod (hereafter, Novgorod), Pskov, Smolensk, Staraya Russa, Staraya Ryazan’, Tver’, and Torzhok.

Birchbark letters may be as small as 6 x 1.5 cm (2 x 0.6”) or as large as 47.2 x 16 cm (18.6 x 6.3”) and were typically trimmed to size after inscription. The bark is smooth to the touch and inscribed on its inside (concave) face – although the outside of the bark, which was harder to inscribe, was also sometimes used. The bark consists of thin layers which may be separated either to reveal smoother underlayers which are easier to inscribe, or to create duplicates of letters. Multiple pieces of bark may also be used for a single “text” as witnessed by N419 (letter 419 from Novgorod), a booklet from the fourteenth-century. Many authors wrote their own letters; however, scribes were sometimes employed as evidenced by surviving “blocks” of letters written in the same handwriting.

Letters were rolled up for travel and carried by messengers within a city or to other cities in Rus’. Messengers sometimes read their messages aloud, performed physical gestures such as bowing, and provided further details to the letters’ addressees (in what are known as “communicatively heterogenous” letters). Space was sometimes left beneath a message for a reply, and occasionally, a single letter witnesses a message and response (indicating that the same letter was sent back and forth). Letters were often read and then discarded, however, as Kirik of Novgorod (d. 1156/8?) recounts in his Questions to the Archbishop of Novgorod (1130—56), Nifont: “Is there no sin in walking with one’s feet on letters (gramotam) that someone shredded (izrezav), threw away (vykinyl) […]?”

GEOGRAPHY OF BIRCHBARK LETTERS

Over 90% of extant birchbark letters have been discovered in Novgorod. This is partly due to Novgorod’s thick, slightly acidic, and anaerobic soil which preserves organic materials such as wood, leather, and bone well, and its history of large-scale excavations. The soils of Moscow, Smolensk, and Vladimir, for example, are less suited to preserving organic matter.

Of the 762 extant birchbark letters from the period c. 1100—1300, a total of 678 are from Novgorod, and of these, 415 come from the Trinity archaeological excavation site (troitskij raskop) in Lyudin End on the city’s western (‘Sophia’) side. The period c. 1100—1300 is a particularly interesting one in Rus’ian, and Novgorodian, history. Novgorod was a city in north-western Rus’ (Russia today), approximately 111 miles from St. Petersburg. The city itself was established in the late-tenth century, although the gorodishche, the residence of the Knyaz' (Prince), approximately 1 mile away, dates to the mid-ninth century. During his reign, the Varangian chief Ryurik made Novgorod his capital.

In 1136, the Novgorodians dismissed their prince, Vsevolod Mstislavich, in what is regarded as the beginning of the “Novgorod Republic.” Veches, or public assemblies, constituted of the boyars (aristocracy) and headed by a posadnik (“mayor”), repeatedly invited and dismissed the princes of Novgorod until 1410 when a Council of Lords (sovet gospod) was established. Posadniks were elected from boyar families in Novgorod, and conflicts often broke out between boyars and their allies with rival groups. In several instances, posadniks were killed, their estates (and those of their allies) burnt, or else the posadnikship taken from them. Although veches were not unique to Novgorod (there were also veches in Kyiv, Pskov, and Bilhorod Kyivskyi), Novgorod’s veche—which would significantly rival the prince’s authority according to many scholars—and its relationship with the city’s princes is particularly interesting. This picture may, in part, derive from the fact that the Novgorodian chronicles survive. Other chronicles, such as southern Rus’’ Tale of Bygone Years (Pověstĭ vremęnĭnyxŭ lětŭ [PVL]), were merely continuations of one another.

Novgorod’s economic position was also unique. The area around the city was heavily forested and well-populated with animals whose furs were exported via Novgorod. The Novgorodian boyars were heavily involved in the fur trade, as well as other economic practices such as moneylending and tax collections from tributary villages (who often paid their taxes in kind). Unlike Kyiv and other southern cities, Novgorod, so far northwest, was not besieged by the Mongols in the 1240s, although its princes paid tributes to the Golden Horde. During the thirteenth-century, trading posts (kontors) for the Hanseatic League were founded in Novgorod – from which furs and wax were typical exports. Hunting birds, leather items, and footwear were other exports. Novgorod’s independent trade with the League through its kontor ceased in 1478 when the Grand Duchy of Muscovy annexed Novgorod and dissolved its veche. In 1494, the kontor was finally closed.

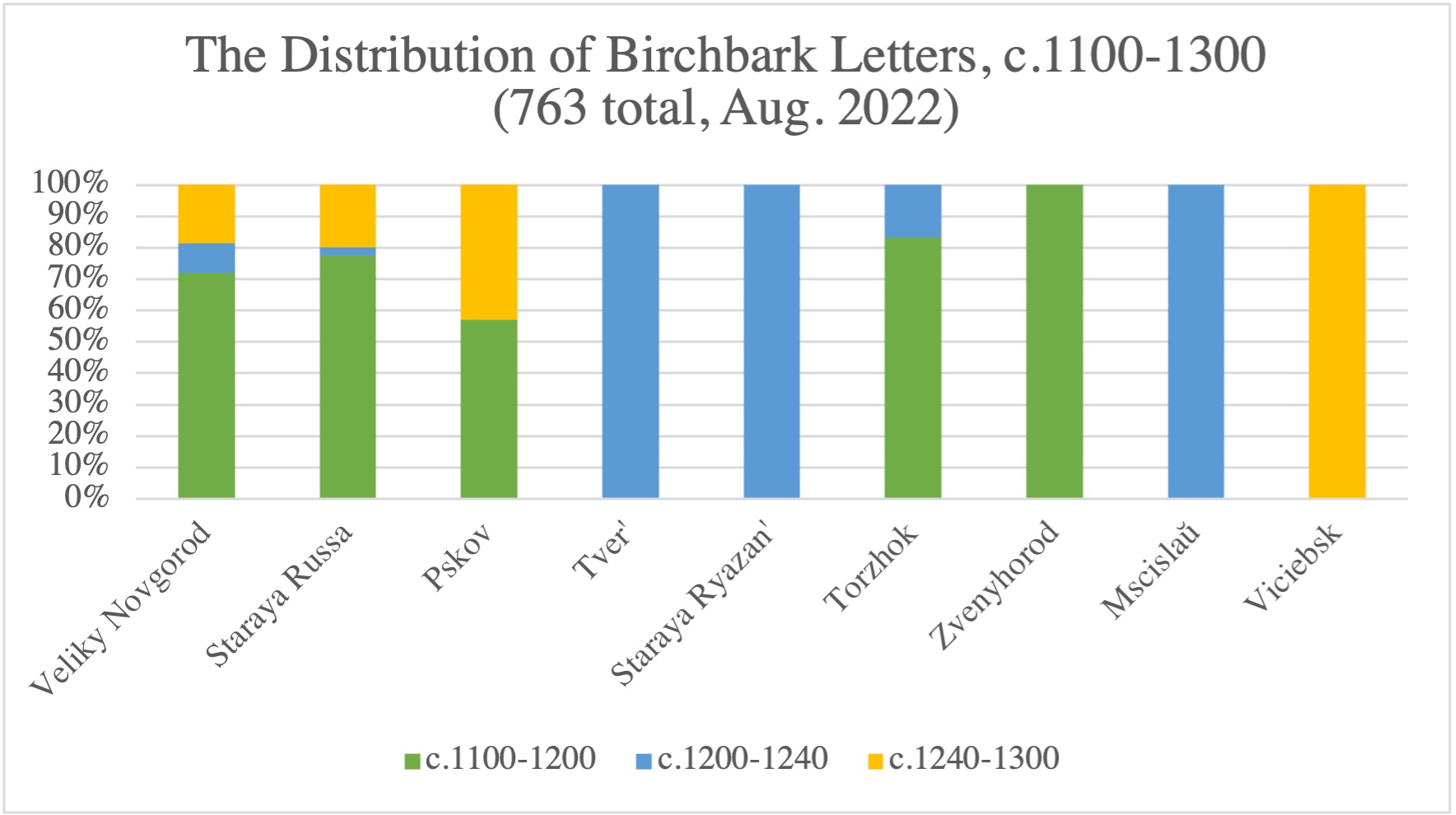

There was a boom in birchbark writing between 1100 and c. 1240. Of the 762 letters dateable from between 1100 and 1300, only 140 were written between c. 1240 and 1300. The decline in birchbark writing likely resulted from the Mongol invasions of Rus’ during the 1230s and 1240s. In contrast, the period c. 1025—1100 witnesses only thirty-six letters, and c. 1300—1500, 415 letters, demonstrating that birchbark writing recovered to some extent during the fourteenth-century.

BIRCHBARK LETTERS, c. 1100—1300: WHOLE NETWORK METHODS AND SOURCES

Here, I have visualised the 762 birchbark letters extant from the period c. 1100—1300 by plotting connections between individual senders and recipients. Although most of the letters visualised here come from Novgorod, nine other Rus’ian cities produced letters represented here: Viciebsk, Zvenyhorod, Mscislaŭ, Pskov, Staraya Russa, Tver’, Staraya Ryazan’, and Torzhok (see table below).

To visualise the whole network, I first read all 762 letters and recorded every name – those of the author(s), addressee(s), and any other person(s) mentioned. Some letters had no discernible author or addressee; however, and thus no names were recorded. I then consulted the Novgorodian chronicles and the works of several linguists, namely A. A. Zaliznyak in his Drevnenovgorodskij dialekt (2004) and the editors of the Novgorodskie gramoty na bereste series (Moscow: 1953-2015), to ascertain in which cases repeated first names referred to one, or three, or five, say, individuals. This was a holistic process based on each letter’s estimated dendrochronological date, estate, and contents.

This process was successful at paring down repeated first names into individuals and, at times, determining their patronymics (and, thus, family links). However, a significant limitation is that in most cases, only first names were used in the letters. Thus, it was not always possible to accurately attribute all letters to specific individuals. The next stage was plotting these individuals into the software Gephi as nodes, and their direct and indirect links: direct between authors and addressees, and indirect between authors/addressees and any persons mentioned in the letters. With such a database, it is then possible to analyse the relational structure of the Rus’ians who sent and received birchbark letters.

PETR MIKHALKOVICH

Here, I consider the ego letter network of boyar Petr Mikhalkovich. Petr was heavily involved in various economic and political activities such as tax and debt collections, the administration of land, and the joint overseeing of a communal court in the Lyudin district or ‘End’ (konets) of Novgorod. As a result, Petr had high social status in Lyudin End – particularly after his daughter, Anastasiya, married the Prince of Novgorod, Mstislav Yurievich, in 1155. Unlike other boyars, however– including members of his family and several of his connections in his letter network (such as the posadnik Yakun Miroslavich) – Petr is not mentioned in any of the local Novgorodian chronicles, though he is mentioned in the PVL – a separate chronicle tradition.

But within the structure of the network of birchbark correspondents, Petr Mikhalkovich was one of the most central figures in the network as measured by betweenness centrality, indicating that he had a large influence on transfers within the network (if transfers follow the shortest possible path).

Betweenness centrality quantifies how often an individual (node) acts as a bridge, or middleman, between two other individuals. Petr also has the highest “Degree” and a very high Eigenvector Centrality within the network. Degree measures nodes as letter authors and recipients and takes account of the number of direct contacts a node has. Nodes with high degree scores sent and received more letters and had more direct contacts than low degree nodes. Eigenvector centrality, on the other hand, measures a node’s centrality in a network; it assumes that a node is more central if it is connected to other central nodes (thus, a person’s social status is partly the sum of their contacts’ social status). Petr Mikhalkovich’s network accounts for 35.82% of connections. For comparison, the second largest component network accounts for 3.9%, and the third largest 2.13%—indicating Petr’s relative importance in the transmission of letters.

Understanding Petr’s potential and realised connections, it is possible to speculate on his level of social, economic, and political power within Novgorod. Petr does not appear in the Novgorodian chronicles unlike other prominent boyars of the time. But the fact that Petr is so central in the birchbark letter network invites us to rethink which sources we should use to understand notions of power, eminence, and social capital in Kyivan Rus’. By mapping people’s connections, it is possible to visualise the groups and individuals a person surrounded themselves with and to whom they communicated most with, as well as to challenge the idea that medieval societies were necessarily rigidly stratified and exclusive in terms of class and/or gender.

CONCLUSION

Studying the network of birchbark letters suggests a new way to consider relationships in Rus’. It not only suggests how these relationships were not only maintained using language and letters as a communicative medium, but also how these relationships impacted macro-structures such as the veche. Specifically, by examining language use in birchbark letters, Rus’ may be brought into wider historical discussions, such as the history of emotions, where it has previously had little presence. Language use in the birchbark letters helps reveal pragmatic and emotional connections between individuals. This should, in theory, make it possible for historians to examine individuals who are not mentioned in the typical sources – chronicles, private acts, statutes—such as Petr Mikhalkovich.

Examining the collection of birchbark letters as a network invites new research about the nature and types of friendship, power consolidation, and their impact on social, economic, and political structures such as the veche.