Luhan’sk

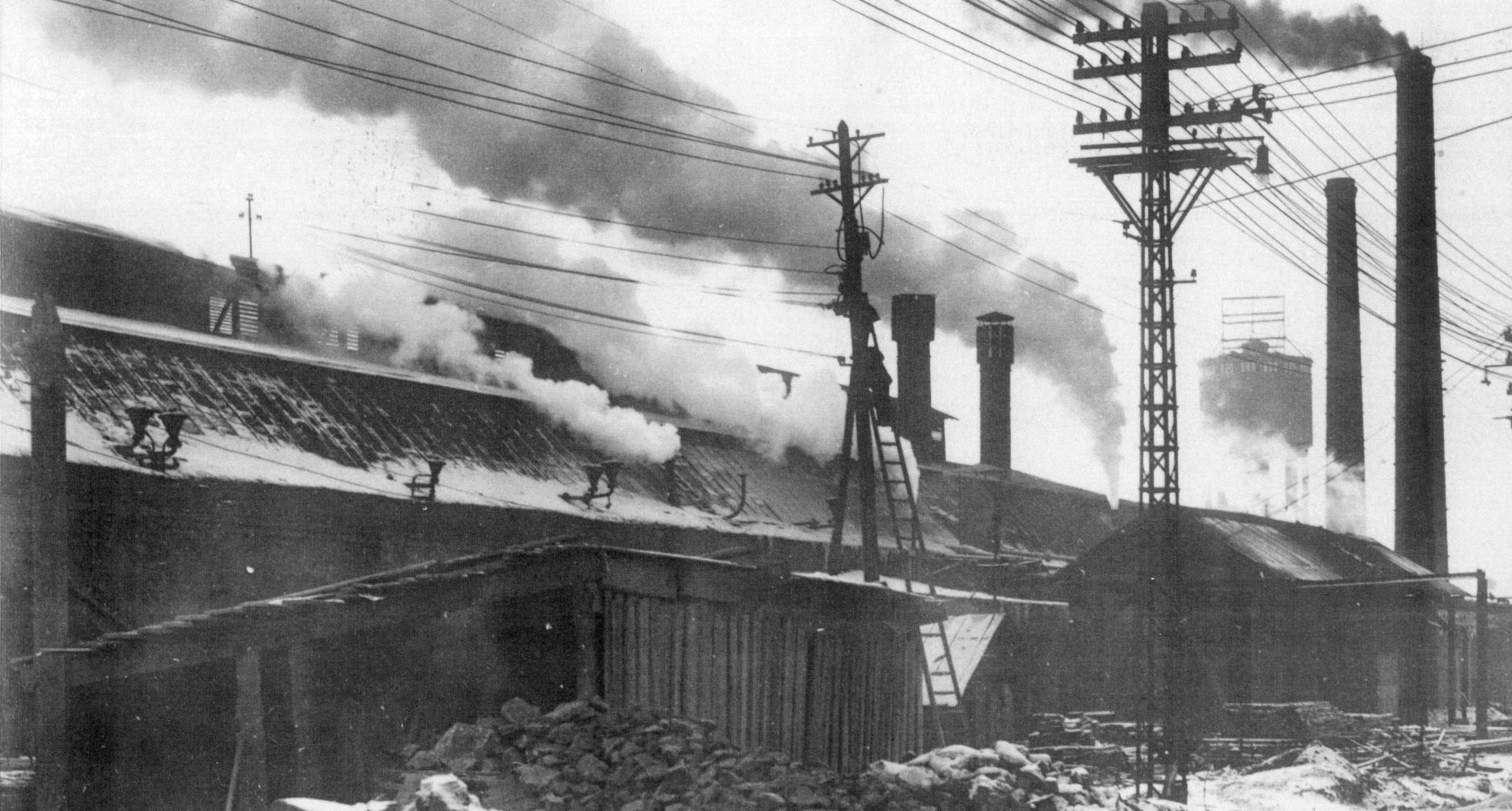

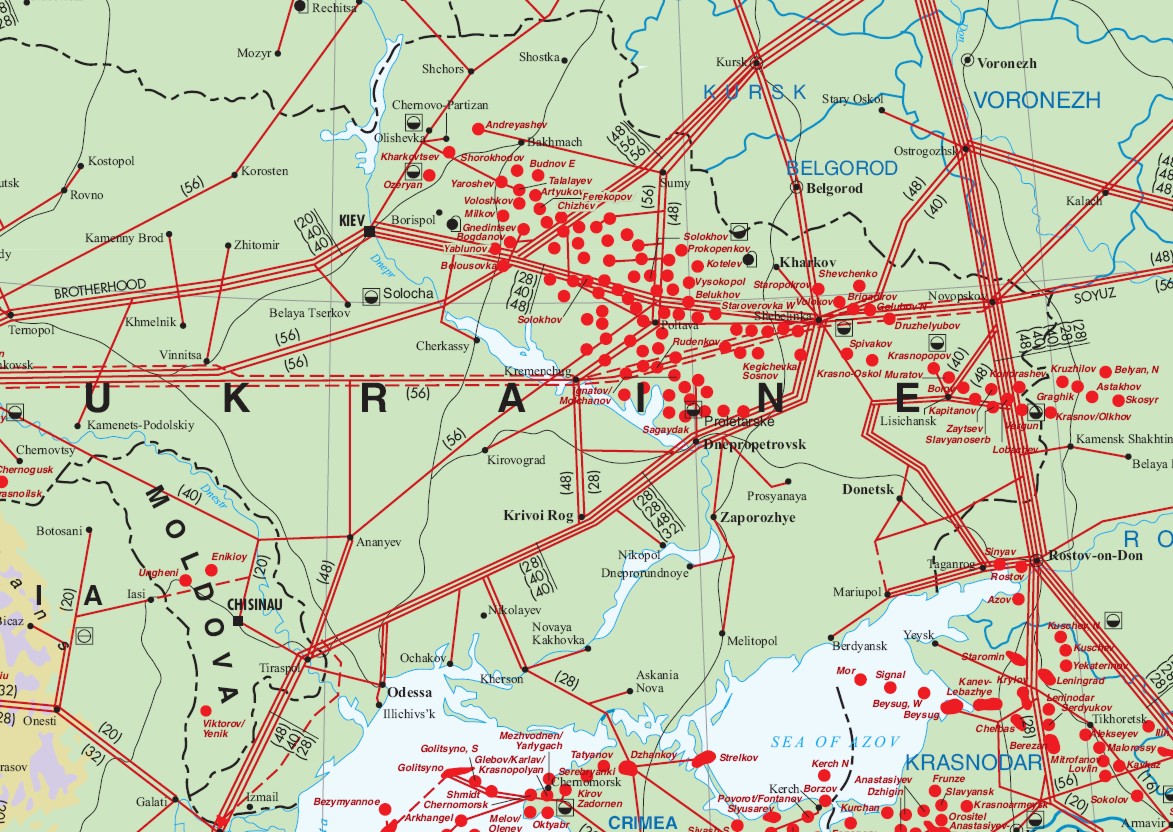

The “Luhan’sk agglomeration,” which is the easternmost regional center of Ukraine, and currently under the effective control of the Russian Federation, serves as a significant hub within the Ukrainian gas transportation system. This is the likely cause of its presence in the map of ultra-emitters of methane. But Luhan’sk is also the epicenter of extensive industrial activity that originated in the 18th century.

Over the past century, Soviet historiography has consistently neglected the multifaceted historical significance of Luhan’sk as an important center in the formation of the industrial region commonly referred to as “Donbas”. The region of Donbas can be characterized as a socio-cultural construct that lacks a distinct and well-defined shape. However, it has been associated with a uniform industrial identity since the era of the Soviet Union. In the prevailing public perception, the demographic composition of the region epitomized the archetype of a “Soviet citizen,” characterized by a strong reliance on the coal mining and metallurgical industries. The narrative surrounding Luhan’sk in particular and Donbas in general is however considerably more intricate. This micro-history explores the entangled history of European industrialization projects, urban development, mass violence, and the somewhat paradoxical involvement in arms manufacturing.

Over the past century, Soviet historiography has consistently neglected the multifaceted historical significance of Luhan’sk as an important center in the formation of the industrial region commonly referred to as “Donbas”. The region of Donbas can be characterized as a socio-cultural construct that lacks a distinct and well-defined shape. However, it has been associated with a uniform industrial identity since the era of the Soviet Union. In the prevailing public perception, the demographic composition of the region epitomized the archetype of a “Soviet citizen,” characterized by a strong reliance on the coal mining and metallurgical industries. The narrative surrounding Luhan’sk in particular and Donbas in general is however considerably more intricate. This micro-history explores the entangled history of European industrialization projects, urban development, mass violence, and the somewhat paradoxical involvement in arms manufacturing.

Luhan’sk was founded in 1795 with the purpose of serving as a stronghold settlement to advance the strategic goals of the Russian Empire within the Black Sea region. In November 1795, the establishment of a state-owned foundry on the Luhan’ River, under the decree of Catherine II, led to the formation of the settlement known as Luhans’kyi Zavod. The factory was established on an empty plot of land and adjacent to the river, in close proximity to the settlement of Zaporozhian Cossacks, known since the 1740s as Kam’yanyi Brid. On the other side of the river Luhan’ there was a settlement where Ukrainian Cossacks had lived for more than fifty years and were involved in trade and crafts. The factory was intended to serve as a significant contributor to the production of arms for the Black Sea Fleet of the Russian Empire.

Looking at the map, it is unclear how the future Luhan’sk, which is situated in the steppes of eastern Ukraine, was connected to the Black Sea. The primary objective behind the establishment of the Luhan’sk Foundry was to serve as a dedicated facility for the manufacturing of naval artillery cannons and associated ammunition. The responsibility for the establishment of this plant was delegated to Charles Gascoigne, a British entrepreneur. In 1794, Gascoigne, an experienced businessman who had previously served as an employee of the British East India Company and held a partnership in a London-based dry-salters firm, embarked on a new endeavor. At the age of 58, having already dedicated approximately a decade to promoting iron foundries and manufacturing cannons within the Russian Empire, Gascoigne received a directive from Empress Catherine II to travel to the eastern region of contemporary Ukraine, which then was part of Empire’s southern frontiers. Gascoigne initiated an investigation into the presence of iron ore and coal reserves. Because there had been previous exploration of abundant coal deposits in close proximity to the future Luhan’sk, specifically within a 90-kilometer radius to the northwest in the present-day city of Lysychans’k, it was anticipated that Gascoigne’s investigation would result in success. The advantageous position of Luhans’kyi Zavod consisted in its being situated in close proximity to deposits of iron ore and coal. It was strategically located on the banks of the Luhan’ River, which forms part of the Don River basin. As a result, Luhans’kyi Zavod was incorporated into the military-industrial complex of the Russian Empire. This integration was prompted, in turn, by the Empire’s desire to fortify its presence in the Black Sea region following its annexation of the Crimean Khanate in 1783.

Once it was integrated into the imperial power structure, the settlement underwent significant development, evolving into a town focused on commerce. By the conclusion of the 18th century, the settlement of Luhans’kyi Zavod had already established itself as a prototypical state-owned manufacturing facility. A number of skilled workers were dispatched to the location from various iron foundries within the empire, a few of which were also linked to Gascoigne’s earlier enterprises. The smelting of iron commenced as early as the year 1800. Simultaneously, the initial prototypes were showcased: a cannonball, a bomb, and a grenade, considered to be among the earliest instances of artifacts crafted exclusively from local minerals. The plant initiated the production of cannons, shells, grenades, and other weaponry, subsequently providing the Black Sea Fleet with these armaments. The Luhan’sk Foundry was highly productive in defense-related activities throughout the various conflicts of the 19th century in which the Russian Empire was engaged.

The Luhans’kyi Zavod was affiliated with the Ministry of Finance of the Russian Empire during the early 19th century, specifically through its inclusion in the Ministry’s Department of Mining and Salt Affairs. But its primary objective was to cater to the military requirements of the Navy. During the French invasion of Russia in 1812, the Russian army was supplied with cannons and cannonballs by the Foundry. By the mid-19th century, there had been notable advances in supplying the infrastructure of the Black Sea Fleet in the southern regions of present-day Ukraine, specifically in Mykolayiv, Kherson, and the Crimean Peninsula. As a result, the significance of the Luhan’sk Foundry began to diminish. Over the period from the 1830s to the end of the 19th century, the settlement encountered its first crisis. The initial enterprise experienced a gradual decline in state contracts, while the settlement itself grew and developed. During the second half of the 19th century, Luhans’kyi Zavod saw a significant increase in its population, surpassing 10,000 persons. Additionally, in the mid-1870s, the town was linked to the major regional transportation hub, Debaltseve, through the establishment of a railway connection. Subsequently, in 1882, Luhans’kyi Zavod was granted the status of a county town and was officially renamed as Luhan’sk. Now, the extraction of coal and iron ore in close proximity to the urban area was to become a reason for a new dawn.

.jpg) In conjunction with the achievement of city status, a settlement was endowed with the privilege of local self-governance, while assuming the role of a regional hub for economic advancement and commercial activities. It was thus expected to foster population growth and generate efforts to attract investments. However, the inception of Luhan’sk as an urban center was marred by a somber event - the cessation and subsequent closure of the Luhan’sk Foundry in 1887. The local elite was confronted with the challenge of attracting investment to facilitate urban development, as the presence of heavy industry reliant on coal and iron ore was considered indispensable for the city’s existence.

In conjunction with the achievement of city status, a settlement was endowed with the privilege of local self-governance, while assuming the role of a regional hub for economic advancement and commercial activities. It was thus expected to foster population growth and generate efforts to attract investments. However, the inception of Luhan’sk as an urban center was marred by a somber event - the cessation and subsequent closure of the Luhan’sk Foundry in 1887. The local elite was confronted with the challenge of attracting investment to facilitate urban development, as the presence of heavy industry reliant on coal and iron ore was considered indispensable for the city’s existence.

Following an extensive period of investor exploration, the inaugural mayor, Nikolai Kholodilin, successfully identified a fresh avenue for urban development, which once again pertained to matters associated with warfare. The rearmament of the Russian army with modernized rifles, commonly referred to as Mosin’s rifle, and the subsequent requirements for ammunition, began in 1891. The premises of the former Luhan’sk Foundry were transferred to the Military Ministry of the Russian Empire in 1892, resulting in its subsequent conversion into the Luhan’sk Cartridge Works. Over the course of the next five years, there was a notable surge in industrial activity in the city and its surrounding areas. This was characteristic of the concluding phase of the “long 19th century” in the contemporary eastern and southern regions of Ukraine. It was marked by the influx of significant European capital and an increased demand for coal, steel, and weaponry, primarily driven by state procurement.

Following an extensive period of investor exploration, the inaugural mayor, Nikolai Kholodilin, successfully identified a fresh avenue for urban development, which once again pertained to matters associated with warfare. The rearmament of the Russian army with modernized rifles, commonly referred to as Mosin’s rifle, and the subsequent requirements for ammunition, began in 1891. The premises of the former Luhan’sk Foundry were transferred to the Military Ministry of the Russian Empire in 1892, resulting in its subsequent conversion into the Luhan’sk Cartridge Works. Over the course of the next five years, there was a notable surge in industrial activity in the city and its surrounding areas. This was characteristic of the concluding phase of the “long 19th century” in the contemporary eastern and southern regions of Ukraine. It was marked by the influx of significant European capital and an increased demand for coal, steel, and weaponry, primarily driven by state procurement.

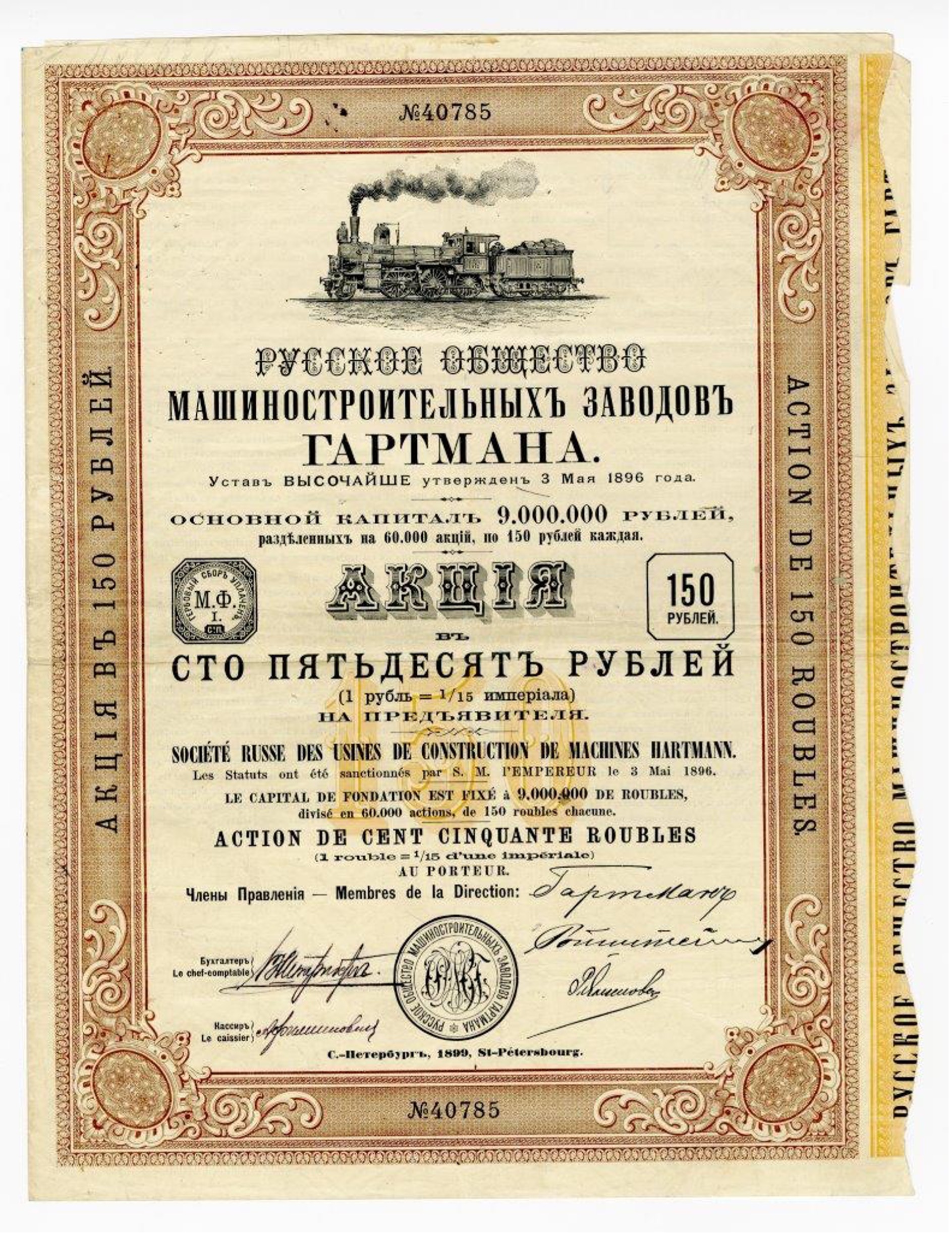

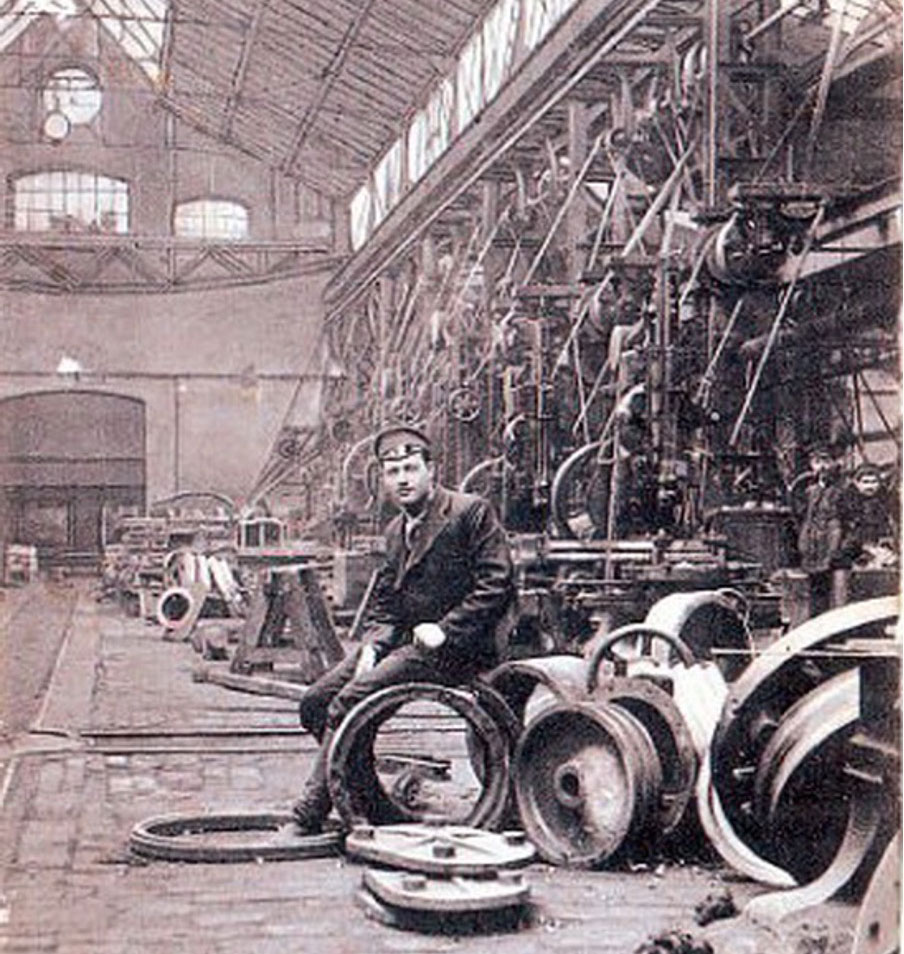

The Donetsk-Yuryev Metallurgical Society was established in 1895 within the area of the methane pollution site identified by the TROPOMI spectrometer, in close proximity to the railway network. This society was founded with the financial support of Alexey Alchevs’ky, a prominent merchant from Kharkiv and one of the richest people in the empire. Over time, the society evolved into the Alchevs’k Metallurgical Complex, which became one of the largest steel works in the region. At the same time, in 1896, Gustav Hartmann, a businessman from the noted German family of industrialists responsible for establishing the important machine-building enterprise in Saxony known as the Sächsische Maschinenfabrik, embarked upon the establishment of the Luhan’sk Locomotive Works (Russische Maschinenbaugesellschaft Hartmann). This particular enterprise, which eventually evolved into the largest locomotive manufacturing facility within the Russian Empire, is presently known as Luhan’skteplovoz.

The Donetsk-Yuryev Metallurgical Society was established in 1895 within the area of the methane pollution site identified by the TROPOMI spectrometer, in close proximity to the railway network. This society was founded with the financial support of Alexey Alchevs’ky, a prominent merchant from Kharkiv and one of the richest people in the empire. Over time, the society evolved into the Alchevs’k Metallurgical Complex, which became one of the largest steel works in the region. At the same time, in 1896, Gustav Hartmann, a businessman from the noted German family of industrialists responsible for establishing the important machine-building enterprise in Saxony known as the Sächsische Maschinenfabrik, embarked upon the establishment of the Luhan’sk Locomotive Works (Russische Maschinenbaugesellschaft Hartmann). This particular enterprise, which eventually evolved into the largest locomotive manufacturing facility within the Russian Empire, is presently known as Luhan’skteplovoz.

The rapid industrialization of the city and the surrounding area resulted in a significant increase in population. As evidenced by the 1897 census data, the urban population in the vicinity of Luhan’sk and other industrial cities amounted to approximately 24,000 people, constituting roughly 13% of the total population of the district. By 1926, the Luhan’sk district experienced substantial population growth, reaching 615,000 inhabitants. Notably, the urban population accounted for 44.5% of this total figure. During the First World War, the area around the city of Luhan’sk and its environs had played a significant role as a hub for the provision of ammunition, including bullets and shells, as well as coal, to the military forces. Throughout the period of the Civil War spanning from 1917 to 1921, the city underwent multiple instances of occupation, carried out by both Bolshevik and monarchist (White) forces.

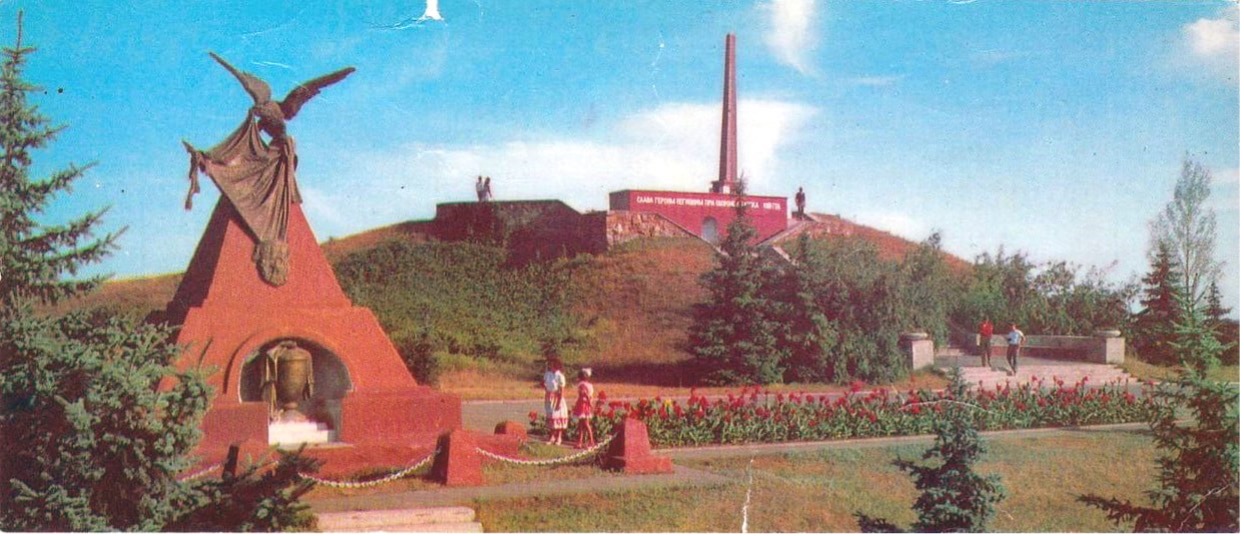

In the spring of 1919, the citizens of Luhan’sk engaged in a defensive effort against the encroaching “White Army” led by Anton Denikin. Notably, this defense took place in close proximity to the location that has been identified as a source of methane pollution by the TROPOMI spectrometer. During the battle, the Cartridge Works coordinated the transportation of shells for defensive purposes to a location approximately 8 kilometers away from the methane site. Subsequently, the remaining distance to the defense line was covered by citizens who engaged in a manual transfer of cartridge boxes, forming a human chain. In commemoration of the this event, the road was officially designated as “Oborony Street” (Defense Street) in 1938.

The location characterized by the presence of methane emissions has undergone a gradual process of historical development. In the 19th century, the area was predominantly characterized as an uninhabited and barren expanse, serving as a transitional zone connecting various settlements, including old Cossack communities, trade routes spanning from the East to the West, and the culturally diverse southern borders of the empire. During the 20th century, the city of Luhan’sk experienced growth not only along the river, but also expanded towards the southern direction, facilitated by the favorable topography of the region. The expansion can also be ascribed to the active development of anthracite deposits, which is a high-carbon content type of coal, by both local and European entrepreneurs. The expansion of the railroad network played a significant role in this process.

Up to the early 1930s, the southern part of the city, which includes the site of methane pollution identified by the TROPOMI spectrometer, remained mostly uninhabited. However, the industrial sector of the city was progressively extending its presence into this area. In the 1930, a military pilot school was established in close proximity to the location, accompanied by the development of various supporting facilities such as a runway (which remains visible and intact to this day), engineering and fuel infrastructure. Later on, the school underwent a transformation and evolved into the esteemed Higher Aviation School of Navigators, thereby catalyzing the development of a surrounding residential area.

In the 1930s, the region also started to search for possibilities of underground coal gasification. This culminated in the establishment of an underground coal gasification facility in the town of Lysychans’k, located north of Luhan’sk, towards the end of the decade. Analogous procedures were implemented in numerous coal districts with the objective of providing local manufacturing facilities with an on-site gas supply. In the mid-1930s, plans were set up for using coke oven gas for the purpose of supplying the machine-building industry in Luhan’sk and its surrounding agglomeration, as well as to facilitate the distribution of gas for residential use. This development was prompted by the significant growth observed in the coal mining and coke industry during that period. In 1938, during discussions regarding the gasification plan for the region, the local press highlighted that approximately 30% of the coke oven gas produced in the entirety of the Donbas region was either combusted within ovens or released into the atmosphere. Hence, a proposition was put forth to construct the Stakhanov-Bryanka-Alchevs’k -Luhan’sk gas pipeline, with the aim of establishing a connection between major coal and metallurgical industries that generate coke oven gas and the Luhan’sk Locomotive Works. The construction began was towards the end of 1940. It was then halted due to the outbreak of the Soviet-German war on June 22, 1941.

Throughout the course of the war and the Nazi occupation of the region, a significant portion of the local industry was relocated to the Urals, accompanied by both personnel and machinery. Items that were unable to be evacuated were frequently destroyed, while the coal mines were flooded with water. At that moment, of course, no one spared any thought for the negative effects on the environment.

A few kilometers southeast of the location the TROPOMI spectrometer identified, one of the worst tragedies in the history of Luhan’sk—the mass murder of the city’s Jewish population—took place during the occupation. The overwhelming majority of local Jews who perished during the Holocaust were executed by bullets next to pits, ditches, and ravines, rather than within gas chambers and extermination camps. On November 1, 1942, most of the Jews who were still in Luhan’sk, exceeding 5,000 individuals, were shot dead near an anti-tank ditch. Following the city’s liberation in February 1943, the number of surviving Jews was at most 100 individuals, in stark contrast to the thriving community that had surpassed 11,000 members in the late 1930s.

Following the liberation of the region from Nazi occupation, the subsequent phase of reconstruction began. The extent of the devastation was primarily attributed to the destruction of infrastructure by the Soviet administration during their withdrawal, rather than being predominantly a result of military action. The region was in need of the return of specialized personnel who had previously been evacuated, along with the acquisition of new equipment and the restarting of development projects.

Prior to the beginning of the war, Luhan’sk and its surrounding areas had meanwhile initiated efforts to explore and extract natural gas resources. The initial exploration of the first well within the city occurred in 1932. In 1938, under the directive of Lazar Kaganovich, the People’s Commissar of Heavy Industry of the Soviet Union, there was extensive exploration of gas fields within the agglomeration, especially in locations close to the mining settlements. Gas and oil deposits were discovered in the area in 1939, leading to the installation of drilling rigs by the spring of 1940.

Following the end of the war, there was a sustained expansion in the exploration and exploitation of gas fields. By the mid-1960s, a total of four gas fields had been discovered in close proximity to Luhan’sk. The construction of a gas pipeline was successfully concluded in 1973, facilitating the transportation of gas to Luhan’sk from those fields. The fields in question were relatively small in size, and their contribution to the overall consumption of the region during the 1970-80s was no more than 10-15%.

Local gas production capacity was limited to meeting the demands of the local population and industries. But during the post-war reconstruction of the city, there was a surge in efforts to enhance industrial capabilities in both the urban area and the agglomeration. The discovery of additional coal deposits led to an increase in population in Luhan’sk. By 1956, the city’s population exceeded pre-war levels, reaching over 250,000 people. By the late 1970s, the population of the city and its surrounding areas approached half a million individuals. The rationale behind Soviet urbanization was predicated on the notion that the urban populace ought to be engaged in local industrial activities, thereby serving as the vital force driving the city’s development. In exchange for their contributions, urban residents were allocated a modest (albeit minuscule) living space. As a result, the burgeoning industry and expanding residential sectors in the southern region necessitated a supply of gas.

Although Luhan’sk’s industrial gasification began in the 1930s, the first gas service to homes didn’t start until 1957. The allocation of gas resources to the general populace did not align with the region’s developmental trajectory, as the primary focus remained on meeting industrial demands. The city underwent gasification following the identification of the Stavropol gas field in the North Caucasus, which subsequently led to the establishment of the Stavropol-Moscow gas pipeline. The gas pipeline traverses the Luhan’sk Oblast, maintaining its trajectory from the southern to the northern parts of the region. By the onset of the 1960s, the region had witnessed the construction of over 1000 kilometers of gas trunklines, along with the establishment of 15 gas distribution stations and 3 compressor stations.

By the early 1990s, the majority of local gas reserves within the Luhan’sk region and its vicinity had been depleted. The gas infrastructure had been developed as an integral component of the Stavropol-Moscow project. By 2014, the Luhan’sk Linear Gas Pipeline Department had been established and was responsible for the operation of approximately 2,000 kilometers of gas pipelines. Additionally, the department managed a network of 50 gas distribution stations and 4 compressor stations, all of which were maintained by nearly 800 employees. As anticipated, the location detected by the TROPOMI spectrometer is situated in close proximity to the linear trunk pipelines, approximately 12 kilometers to the south of the compressor station.

The birth of an environmental movement can be seen as a likely consequence of the collapse of the Soviet Union in a highly industrialized and densely populated region situated to the south of Luhan’sk, specifically in the coal areas where the population density exceeded 150 individuals per square kilometer. Nevertheless, the sole manifestation of environmental activism in Luhan’sk during the 1990s pertained exclusively to the aftermath of the tragedy at Chernobyl and the advocacy for the rights of those involved in its containment efforts. Simultaneously, the miners’ movement in the Donbas region exhibited significant activity. Commencing from the summer of 1989, the occurrence of miners’ strikes in the area, coupled with their unwavering support for Ukrainian independence movements, undeniably exerted a profound impact on the subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Union. Following its independence, the nascent Ukrainian nation assumed control over a substantial coal and metallurgical sector located in the Donbas. It is worth noting that this industry did not consistently generate profits within the framework of a market-based economic system. As a result, the coal mining sector experienced a deficit, leading to the inability to remunerate miners, thereby prompting their decision to engage in a strike.

In the case of Luhan’sk, a notable event occurred in 1998, wherein a group of approximately 250 miners from four mines staged an occupation of the park situated in front of the regional administration building. This occupation persisted throughout the summer, with the miners consistently besieging the premises on a daily basis. Their primary demand was the remuneration of unpaid wages spanning a period of 2.5 years. The protest, commonly referred to as the “Great Picket,” escalated the local conflict significantly, resulting in a confrontation with riot police on Independence Day (August 24th) and subsequently culminating in an act of self-immolation by Oleksandr Mykhalevych, one of the miners, on December 14, 1998. The repayment of the debt to the miners occurred on December 17th.

In the case of Luhan’sk, a notable event occurred in 1998, wherein a group of approximately 250 miners from four mines staged an occupation of the park situated in front of the regional administration building. This occupation persisted throughout the summer, with the miners consistently besieging the premises on a daily basis. Their primary demand was the remuneration of unpaid wages spanning a period of 2.5 years. The protest, commonly referred to as the “Great Picket,” escalated the local conflict significantly, resulting in a confrontation with riot police on Independence Day (August 24th) and subsequently culminating in an act of self-immolation by Oleksandr Mykhalevych, one of the miners, on December 14, 1998. The repayment of the debt to the miners occurred on December 17th.

In 1999, miners made several attempts to capture the center of Luhan’sk. These incidents were subsequently commemorated by the mining community on August 24 and December 14, which were informally recognized as days of remembrance for these events. The concern regarding ecology among city residents did not primarily revolve around advocating for clean air and a healthy environment, as such aspirations were perceived as unusual. Instead, the focus was on demonstrating respect for individuals employed in the most hazardous working conditions.

After the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War in the spring of 2014, the gas transportation network within the region and oblast was divided. Specifically, the southern portion came under the management of Russian companies, which effectively exerted control over the occupied region, while the northern section remained under the operation of a Ukrainian company. Our knowledge regarding the management of the city and its infrastructure thus remains limited. It is evident that the infrastructure in Luhan’sk is undergoing a gradual deterioration. A notable instance of this decline is the dismantling of the city’s tram network, which has been in operation since 1934.

The destruction of infrastructure has significant implications for environmental degradation. The mines “Luhan’ska” and “Mashchins’ka,” located near Luhan’sk, experienced significant damage during the battle for control over the city in the summer of 2014. As a result, these mines have become inundated with water and are no longer operational. Presently, a mere 97 out of the total 220 coal mines situated in the Donbas region were in active operation (as of 2021), with the remaining mines undergoing either the liquidation process or being inundated with water. The magnitude of the environmental disaster that Ukraine will potentially encounter following the liberation of the region is progressively escalating. This exacerbates the existing issues of mine contamination and loss of human lives.

The destruction of infrastructure has significant implications for environmental degradation. The mines “Luhan’ska” and “Mashchins’ka,” located near Luhan’sk, experienced significant damage during the battle for control over the city in the summer of 2014. As a result, these mines have become inundated with water and are no longer operational. Presently, a mere 97 out of the total 220 coal mines situated in the Donbas region were in active operation (as of 2021), with the remaining mines undergoing either the liquidation process or being inundated with water. The magnitude of the environmental disaster that Ukraine will potentially encounter following the liberation of the region is progressively escalating. This exacerbates the existing issues of mine contamination and loss of human lives.

Currently, ongoing discussions are being held with international partners regarding the prospective reconstruction of Luhan’sk and the entirety of Donbas. While currently in the planning stage, the United Nations Recovery and Peacebuilding Program is actively formulating strategies to facilitate coordination among communities, authorities, and businesses in the reconstruction process following the end of the occupation. In the spring of 2023, President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine presented a proposal to international partners regarding a model of regional recovery known as “patronage.” This model entails countries assuming a role in supporting the recovery of specific regions, industries, or communities. Thus far, the task for leading the reconstruction efforts in the Luhan’sk region has been extended to three nations: the Czech Republic, Sweden, and Finland.

Luhan’sk, like the larger Donbas region, is currently confronted with the multifaceted ramifications of the war, encompassing the loss of human lives, the displacement of the people, or their tragic deaths due to their forced conscription into the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation. The region is at the same time confronted with environmental adversities. The area characterized by methane pollution represents a singular instance within the broader extent of environmentally hazardous and unsuitable areas. A region whose history over the past 200 years has been solely associated with the constant acceleration of industrialization runs the risk of becoming an over-polluted wasteland if these industries are not managed properly.