Yenakiieve

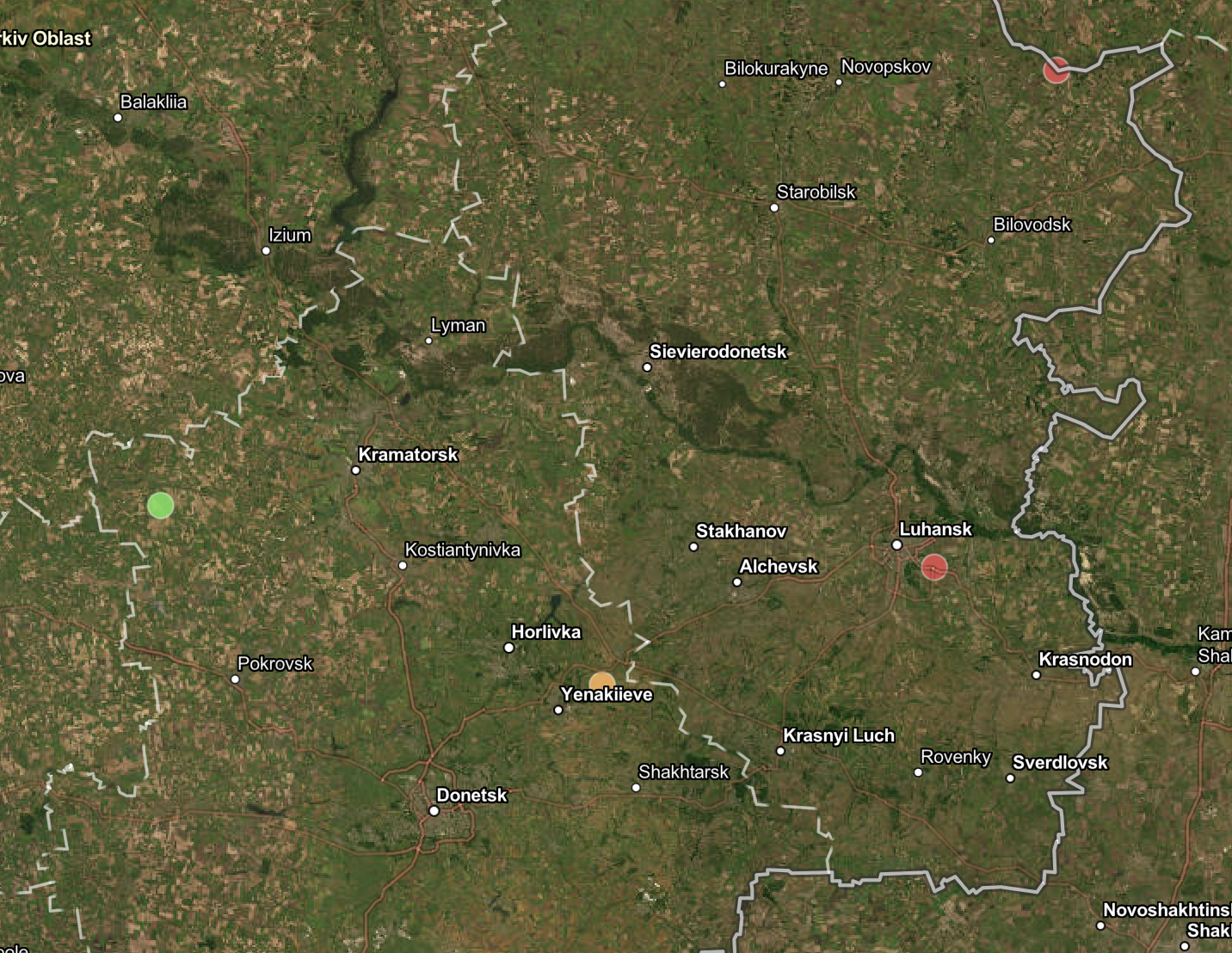

Of the 1,797 sites of ultra methane emissions identified by the TROPOMI spectrometer, 650 are in the territories of the former Soviet Union. Four are in the old industrial region of Donbas in eastern Ukraine. All have been sites of terrible loss in the present war. All were sites of conflict in World War Two. All are sites of history and memory, in the long economic history of Europe. All are places of environmental desolation.

Of the 1,797 sites of ultra methane emissions identified by the TROPOMI spectrometer, 650 are in the territories of the former Soviet Union. Four are in the old industrial region of Donbas in eastern Ukraine. All have been sites of terrible loss in the present war. All were sites of conflict in World War Two. All are sites of history and memory, in the long economic history of Europe. All are places of environmental desolation.

Two of the sites, of emissions connected to oil and gas, are in the eastern part of the Donbas. One, somewhere within the circle of 15km in radius that the sites on the map depict, is a little way to the south of the old iron-making town of Luhansk, on the road and railway line to the Sea of Azov. This is also the route of oil and gas pipelines from Russia to the east and west, which are likely to be the source of the emissions. The other is in the northeast of Luhansk province, near the tiny village of Lypove. It is also close to pipelines, and to the border between Luhansk and Voronezh.

Two of the sites, of emissions connected to oil and gas, are in the eastern part of the Donbas. One, somewhere within the circle of 15km in radius that the sites on the map depict, is a little way to the south of the old iron-making town of Luhansk, on the road and railway line to the Sea of Azov. This is also the route of oil and gas pipelines from Russia to the east and west, which are likely to be the source of the emissions. The other is in the northeast of Luhansk province, near the tiny village of Lypove. It is also close to pipelines, and to the border between Luhansk and Voronezh.

There is a site connected to "other human activities" in the western part of the Donbas, in the vicinity of the village of Stepanivka. It is 70 kilometers to the west of the industrial town of Kramatorsk; Kramatorsk is where some 50 people were killed at the railway station by short-range ballistic missiles, on the morning of April 8, 2022. Stepanivka is surrounded by agricultural land and the meanderings of the Samara river. There is a settlement that looks (from the air) like a deserted, gouged out quarry. There are also residues of explosives from 2014.

The fourth site is of emissions connected to coal. It is near the steel-producing town of Yenakiieve, to the east of the old industrial city of Horlivka. Horlivka was the site of mass murder in World War Two, and again in the war that began in 2014. Yenakiieve is one of the most polluted places in Europe, as measured by the heavy metals in moss. In the outskirts of Yenakiieve, there is a large coal mine in the settlement called Bunhe, or Yunokomunarivs'k.

The fourth site is of emissions connected to coal. It is near the steel-producing town of Yenakiieve, to the east of the old industrial city of Horlivka. Horlivka was the site of mass murder in World War Two, and again in the war that began in 2014. Yenakiieve is one of the most polluted places in Europe, as measured by the heavy metals in moss. In the outskirts of Yenakiieve, there is a large coal mine in the settlement called Bunhe, or Yunokomunarivs'k.

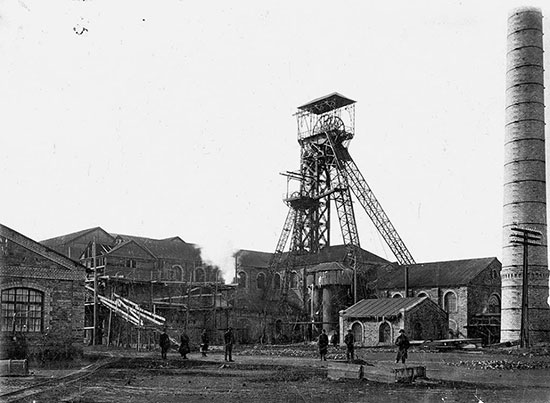

The coal mine in Bunhe -- known as the "YunKom Mine" -- was developed to supply the metal works of Yenakiieve, amidst a boom in Russian-Belgian investment in the early 20th century. The mine was the site, in 1979, of one of the sinister accidents of the carbon-energy system, when Soviet engineers, in an effort to release the methane and other toxic gases trapped in the mine, exploded a small nuclear device 900 meters below the surface of the mine. The mine has flooded on many occasions; the underground water is contaminated with radioactive materials as well as metals. Yenakiieve is surrounded by coal waste in self-heating dumps, visible to the LANDSAT satellite overhead; there is extreme air pollution visible to TROPOMI, especially nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide.

There has been intensive coal production in the Donbas since the 1890s. But the coal beds are thin, in shallow tectonic strata. They were layered with gases, especially methane, even before the deep excavations of the 20th century. The mines are among the "gassiest in the world," and the high methane content poses a "severe mine safety problem." There is a risk of explosions and asphyxiation. The mines are the source, still, of water, air, and soil pollution. In the large Zasyadko mine, opened in 1958, there have been multiple disasters over more than a generation; 101 miners died there in 2007. The shore of the Sea of Azov, near Mariupol, is edged with the waste of steel production, "sludge" and "ash".

There has been intensive coal production in the Donbas since the 1890s. But the coal beds are thin, in shallow tectonic strata. They were layered with gases, especially methane, even before the deep excavations of the 20th century. The mines are among the "gassiest in the world," and the high methane content poses a "severe mine safety problem." There is a risk of explosions and asphyxiation. The mines are the source, still, of water, air, and soil pollution. In the large Zasyadko mine, opened in 1958, there have been multiple disasters over more than a generation; 101 miners died there in 2007. The shore of the Sea of Azov, near Mariupol, is edged with the waste of steel production, "sludge" and "ash".

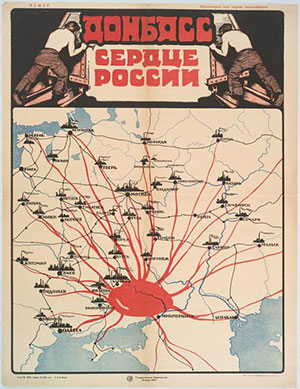

In war, space becomes two-dimensional. The Donbas, which is, or was, a land of around 6 million individuals, with memories of the past and fears of the future, has become little more, in the eyes of the world, than arrows on a map. But it is also a land of enduring importance in the economic history of Europe, and in the history of environmental loss.

The Donbas has been a place of many identities and many languages for more than two hundred years; a land of immigrants and sojourners. It was the site of prodigious economic development around the coal of the Donets basin, and by 1913, it supplied more than 80 percent of the coal used in the Russian empire. It was the site, too, of innovation in the organization of work; of "liberal capitalism" in the 1890s, and of the "scientific management" of labor in the 1920s. Alexei Stakhanov -- "Stakhanovism's great Stakhanov" -- who was born in a small town south of Moscow, moved to the Donbas to work in a coal mine to the east of Kramatorsk. There were Belgians and Poles, Lithuanians and Jews and Greeks.

In World War Two, there was a new map of horror in the Donbas, occupied by the Nazis as a region of industrial importance. Horlivka and Artemivsk, Donetsk and Mariupol: these were centers of commerce and Jewish life, and became the sites of mass murder in 1941-1942.

In World War Two, there was a new map of horror in the Donbas, occupied by the Nazis as a region of industrial importance. Horlivka and Artemivsk, Donetsk and Mariupol: these were centers of commerce and Jewish life, and became the sites of mass murder in 1941-1942.

The Soviet economy of the Donbas, in the end, was a dystopia of energy and destruction. But it was also, for a time, a source of hope. Even the sound of economic life in the Donbas, in Dziga Vertov's Enthusiasm, was the sound of modernity. In the postwar reconstruction of the 1940s, it was the landscape of the Donbas that promised a new society, of salubrious and skilled work for all (like the women and men of the Donets Industrial Institute in 1947). In the maxim of the director Leonid Lukov -- born in the now devastated port city of Mariupol in 1909 -- "when studying the present world, it’s important not only to confirm what exists, to recognize what is happening; you [also] have to see the main thing: the future.”

It is not too soon -- it is never too soon -- to think about the world after the war. To imagine the environmental reconstruction of Ukraine is in turn to think about the connections between the different crises of our own times. The tragic history of the Donbas is layered in the old towns and villages that were the sites, in 2019-2020, of the ultra methane emissions. But it is a history, too, that shows the connections between the local and "global" environment. It shows, with terrible exactitude, how proximate are the causes of climate change to the ordinary, enduring pollution of soil, water, air and the conditions of work.

To reduce methane emissions has been seen an almost effortless, weightless policy for limiting climate change. Methane is more than 25 times as potent as carbon dioxide in trapping heat in the atmosphere. It is also a relatively light gas; lighter than air. It is colorless and odorless and untoxic. It can be captured and re-used, with well-established and not immensely expensive technologies. These are light policies, almost weightless.

To reduce methane emissions has been seen an almost effortless, weightless policy for limiting climate change. Methane is more than 25 times as potent as carbon dioxide in trapping heat in the atmosphere. It is also a relatively light gas; lighter than air. It is colorless and odorless and untoxic. It can be captured and re-used, with well-established and not immensely expensive technologies. These are light policies, almost weightless.

In the Donbas, history and memory are heavy. In the towns that are the sites of methane emissions, the global pollution of greenhouse gases is contiguous to the local pollution of land, water and air. Economic history is heavy, there, and so is the history of environmental destruction. There are heavy metals, heavy equipment, heavy munitions, heavy industry. It is a heavy history, in Stepanivka and Yenakiieve.

In the world after the war, these are the towns and villages to be restored. There were environmental movements in Ukraine before the present war, and environmental movements in Russia. The miners' strike of 1989 in the Donbas, immediately before the fall of the Soviet Union, was about safety and pollution, as well as perestroika. There have been weightless climate policies (the exchange of carbon dioxide quotas for methane emissions, in Ukraine) and studies of pipeline safety (in Russia.) In Horlivka, there was a toxic site, an old explosives factory, that was restored, and in Kramatorsk, there was a "wind park." To throw away entire regions -- to not see the Donbas, or the old industrial settlements of other countries -- is to close off the possibility of preventing catastrophic climate change. One way to understand the connections between the many crises of 2022-2023 is to imagine what it would be like to invent a different future.