The worst natural disaster in Europe in a century. That's how the regional director of the WHO described this month's twin earthquakes in Turkey and Syria. The arithmetic of the loss alone is staggering—to say nothing of the emotional toll, which is incalculable. At least 41,000 people have died in Turkey. Some 6,000 are dead in Syria. And on both sides of the border, hundreds of thousands are displaced.

How to understand a disaster of this scale? With a tragedy so superlative, which tools, psychological and intellectual, suffice? Is it possible to historicize 2023's disaster, without normalizing it? These are the questions I'm wrestling with, both as a historian and as someone who's spent years in the region. While teaching and conducting research along Turkey's Black Sea coast, I've also had the privilege to travel widely in Anatolia—including to Gaziantep and Şanlıurfa in 2014.

Remarkably, until quite recently, the humanities have neglected natural disasters as a subject. While some calamities have long been iconic, such as Mt. Vesuvius' eruption in 79 CE, most were too sudden, too infrequent, and too natural to take center stage in human history. This has all changed in our century, when ecological crises like climate change are rarely far from mind. Steeped in the new catastrophic thinking, scholars across disciplines have reassessed the role of natural disasters in human life.

Three concepts from this field, which usually goes by "disaster studies," strike me as particularly salient for the current moment—precarity, contingency, and resilience. This essay will address each in turn, primarily in the Turkish context, as a preliminary attempt to think through the unthinkable.

Precarity: Cracks in the Foundation

In the drama of Turkish history, a recurring character is that of the economic booster, who claims to hold blueprints to a brighter future. From American modernization theorists to would-be politicians, these figures trumpet Turkey's vast—yet ostensibly unrealized—natural potential: its abundant sunshine, fertile soil, three coasts, and situation "at the crossroads of Europe and Asia."

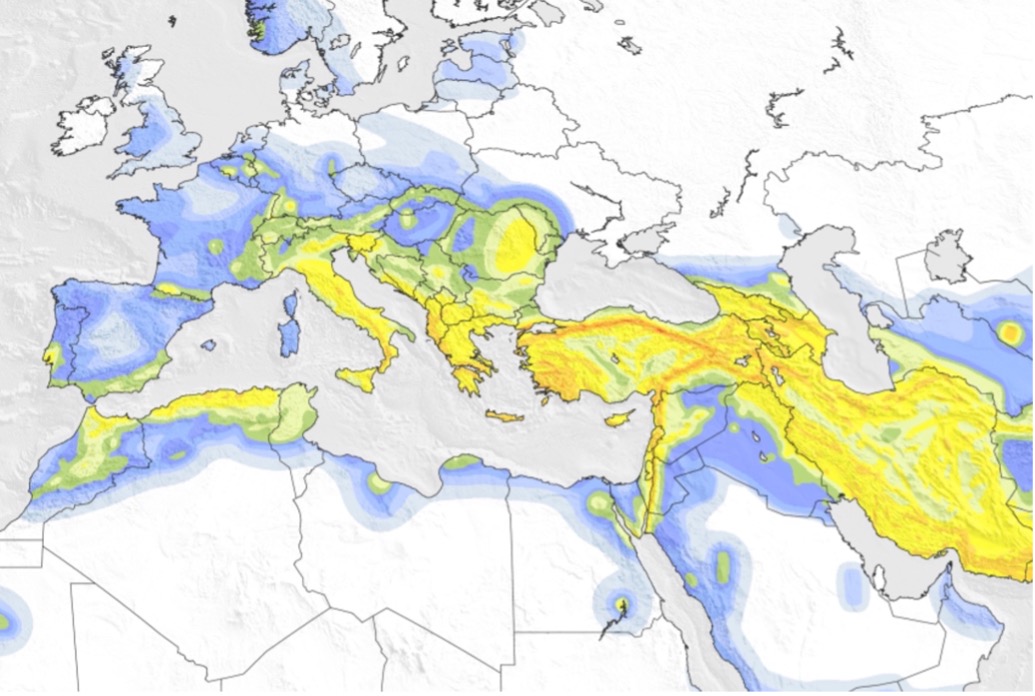

But beneath these optimistic refrains, the historian also detects a drumbeat of anxiety about the subterranean threat. Anatolia straddles two major fault lines, which hang like Damocles' sword over even the most rapturous plans. The question for the booster then becomes: back down—or forge ahead, tectonics be damned?

In Turkey as elsewhere, seismic precarity is thus the product of both geophysical reality and human decision-making. Foremost among the disaster scholar's tools is the conviction that all "natural" disasters are "never 'natural' in the true sense of the word." Rather, natural phenomena—even those as acute as earthquakes—become disasters only when they clash with social vulnerabilities.

This troubled relationship between seismic risk and human agency has a deep history in Anatolia. That earthquakes have menaced successive civilizations is on display everywhere in Turkey. Look closely at the monuments for which the country is rightly famous, and you'll find the scars of past calamities. The Library of Celsus, for example, the jewel of Ephesus, is one of the world's most iconic Greek structures. In truth, archaeologists pieced together the Library's façade in the 1970s; an earthquake toppled the original a millennium ago. The Hagia Sophia's awesome dome too has been reconstructed; tremors collapsed Emperor Justinian's original in 558 CE.

As for the 2023 earthquakes, they ripped along Turkey's border with Syria, where the layers of human precarity overlap like sediment. The region's historical and religious heritage is immense—from Göbekli Tepe, a Neolithic shrine, to Antakya's mosques and churches. Yet since the twilight of the Ottoman order, the borderland has witnessed considerable strife. Under Sultan Abdülhamid II and then the Young Turks, for example, Ottoman soldiers drove Armenians from their homes. And in the 1930s, the Turkish Republic and Syria, then a French mandate, nearly came to blows over the Hatay Province—a territorial dispute that triggered another mass exodus.

The Syrian Civil War has again belied the fiction of the hermetically sealed nation-state. Turkey, in addition to being a combatant, hosts roughly 4 million of the conflict's 5.6 million refugees (along with 300-500,000 Afghans). As others have pointed out, this year's earthquakes have thus compounded the trauma of war, terror, and poverty with yet more displacement. (There is a climate dimension too to this crisis: severe drought likely helped to spark the civil war in 2011.)

Contingency: A Molten Moment

Natural disasters, by shattering the status quo, create a lot of room for contingency. The "earthquake" is a common metaphor for great historical change, but it can also set such changes in motion. In laying bare a society's fracture-points, natural disasters expose the corruption or inequality of a given political system. Governments as divergent as the Soviet party-state and Mexico's Institutional Revolution Party have sped their downfalls by botching rescue efforts or by greenlighting shoddy construction.

Turkey's politicians are well aware of this fact. The reigning Justice and Development Party (AKP) rose to power not long after Turkey's last mega-earthquake, which killed some 18,000 in and around Istanbul in 1999. In 2023, with the country's economy on stilts and a high-stakes election scheduled for May 15, both incumbents and opposition have scrambled to cast the earthquake in an expedient light. The latter hope to pin the blame on President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan himself. The AKP administration, meanwhile, has attempted to cushion the blowback by calling a state of emergency, restricting social media chatter, and going after individual contractors for criminal negligence.

Turkey's politicians are well aware of this fact. The reigning Justice and Development Party (AKP) rose to power not long after Turkey's last mega-earthquake, which killed some 18,000 in and around Istanbul in 1999. In 2023, with the country's economy on stilts and a high-stakes election scheduled for May 15, both incumbents and opposition have scrambled to cast the earthquake in an expedient light. The latter hope to pin the blame on President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan himself. The AKP administration, meanwhile, has attempted to cushion the blowback by calling a state of emergency, restricting social media chatter, and going after individual contractors for criminal negligence.

Beyond electoral politics, we might see any number of contingencies in the international sphere. In demonstrating nature's seeming indifference, disasters have a tendency to clarify our common humanity. In Turkish history, disasters have precipitated new expressions of international solidarity. After a 1911 earthquake struck the Russian Empire, for instance, Ottoman pan-Turkists sent donations to their Central Asian "brothers in religion." And after the 1999 tragedy, "disaster diplomacy" thawed Greco-Turkish relations.

Today's observers have pointed out that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad may be angling for the same post-disaster glow—and that Iranian and Israeli military planes are sharing Turkish tarmac. While the 2023 disaster isn't likely to rewrite Middle Eastern affairs, its ramifications could be wide-ranging. Consider, for example, the global scale-down in nuclear energy following the Fukushima "triple disaster" in 2014. It's conceivable that the 2023 calamity could complicate the AKP's own ecologically risky megaprojects—such as the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant (under contract with a Russian state firm) or the Istanbul Canal.

Resilience: Learning and the Hero City

Natural disasters, for all of their violence, can build as well as destroy. Catastrophes encourage individuals and communities to develop resilience—to learn, adapt, harden, and prepare.

Yet resilience is a treacherous topic. For the millions now suffering in Turkey and Syria—and for those of us grieving abroad—to invoke a "silver lining" is pollyannish at best, offensive at worst. What is more, resilience narratives can serve opportunists, who would rather the post-disaster conversation focus on social harmony than accountability. Still, many are asking: how do we prevent such events from reoccurring?

There's a long track record in Turkish history of such adaptations. Throughout the Ottoman period, the sultan's legitimacy rested in part on his ability to care for disaster-stricken subjects. Local communities, too, developed sophisticated institutions for distributing aid (though, as the historian Yaron Ayalon shows, these reflected religious divides). In the nineteenth century, a string of earthquakes helped to popularize rationalist, rather than theological, explanations for the tremors. These ideas laid the groundwork for modern Turkey's robust seismological tradition. And not least, it was the 1999 Marmara earthquake that instigated the creation of Turkey's central disaster management agency (AFAD), whose representatives have played such a prominent role in recent days.

But these experiments in resilience have faced countervailing trends. Turkey's breakneck urbanization, emblematized in the proliferation of "overnight" gecekondu suburbs, meant that building codes were honored in the breach. Istanbul has grown fifteenfold since 1950—Gaziantep seventeenfold. In the postwar context, where housing required personal initiative, urban planning was ad hoc, and top-notch materials were a luxury, it's perhaps unsurprising that shelter—not a future hazard—took priority. However, the first sight to greet visitors to today's cities is likely a forest of multistory, terracotta-colored apartment buildings. Many of these are of more recent construction—designed not by upwardly mobile rural migrants, but by professional firms, the largest of which enjoy close ties to the government.

The failure of Southeast Turkey's neighborhoods to withstand the tremors therefore follows a decades-long demographic shift from village to city—but also identifiable acts of cronyism, which have weakened oversight and enabled corner cutting. Disentangling the two is a challenge, but history and geography ought not preclude accountability.

The failure of Southeast Turkey's neighborhoods to withstand the tremors therefore follows a decades-long demographic shift from village to city—but also identifiable acts of cronyism, which have weakened oversight and enabled corner cutting. Disentangling the two is a challenge, but history and geography ought not preclude accountability.

Disaster scholars puzzle over the fact that many societies neglect to memorialize natural disasters—particularly when compared to events like war or massacre. It wasn't until the coronavirus pandemic, for instance, that many of us revisited the 1918 Spanish flu—a misfortune long overshadowed by World War I. This tendency to see natural disasters as freak accidents, rather than as manifestations of long-term dynamics, scholars argue, increases a society's susceptibility to the next big catastrophe.

As we assess Southeast Turkey's recovery, then, these are some factors to keep in mind. Years from now, how will Kahramanmaraş and Gaziantep's earthquake victims be memorialized? (Two cities, incidentally, which earned their names as tributes to wartime sacrifice. Kahraman means "hero" and Gazi "warrior".) Or will Turkey and the global community write off February 2023 as a tragic, yet unavoidable accident? President Erdoğan has promised to rebuild the region within a year. When the reconstruction begins, will speed outstrip safety? Will the process be transparent and fair-minded, or will it reinforce the region's partisan, ethnic, and socioeconomic divisions?

Triage

With search and rescue winding down, the relief efforts are entering a slower, more grueling phase. From a historical point of view, the reconstruction will be no less crucial than the breathtaking rescue work. Precarity and resilience, and the contingencies embedded within them, are formed over the long term—decision by decision, brick by brick.

A heartening facet of the relief efforts has been the involvement of international and local NGOs. Groups are still collecting funds for impacted university students, first response volunteers, a needs map, as well as for Syrian refugees. How these kindnesses will create a more resilient future can't be known. But at the scale of individual lives—the scale at which we experience the world—they're key.

Taylor Zajicek

February 2023