On the drizzly days of British summertime some sixty years ago my grandparents used to drive from their little village in the heart of the New Forest to the very edge of the south coast. They bought their lunch from the Barton-on-Sea chippy, climbed to a bench at the top of the cliff and - protected from the winds by headscarf and cap - ate their fish and watched the sea.

To their small grandchild, slowly tracing the coastal paths that featured in their tales of youth, these cliffs seemed ancient, strong, and constant.

Even in the short time since I first walked these cliffs, the paths have become harder to follow. Over the years, the clifftop line has made tiny movements backwards, the rock has weakened, and much of it has fallen in landslides. When I walk there now, I must step further inland, making fresh footprints, weaving around the crevasses in the rock. These new tracks materialise as the cliffs recede, and as the paths are made invisible so too do other things disappear. Benches have been removed; houses have been demolished; coastal plants, victims of the new heat, have dried to a handful of dust. As our island gets smaller the comforting characters of old stories are no longer there. Their absence is painfully visible.

Stabilising erosion has been a local preoccupation for generations. Initially, it was a private land issue for the aristocracy. The Third Earl of Bute - botanist, horticulturalist, and future Prime Minister - built High Cliff Estate overlooking Christchurch Bay in the late eighteenth century, and the approaching sea was a constant source of frustration and cost to the family. As he buried his head firmly in the falling sands, it is said that the Earl's servants regularly ran out to make new paths along the cliff-edge whenever he wanted to venture outside, desperately trying to ensure their master never found out quite how far the cliffs had receded.

The first attempt to tackle the problem head-on was by Louisa Anne Beresford, Marchioness of Waterford, the Earl's granddaughter. Louisa had grown up at Highcliffe and learnt that the causes for landslips were often due to the waterlogged soils of the under cliff. Spending vast sums of personal wealth to address the risks, in the 1880s she implemented drains and groynes to successfully navigate land water down to the sea and alter the course of a nearby river.

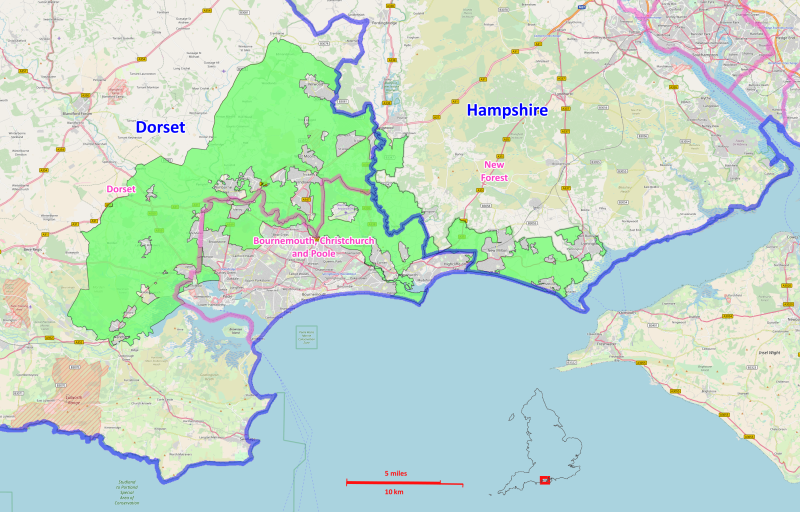

In 1927 the freehold of the clifftop was purchased by the Parish Council and responsibility fell to local authorities. Throughout the century, as houses dropped from the cliffs and residents demanded action, wooden groynes, rock armouring, sunken boreholes, filter drains, and sheet piling were added and restored to the coastline with a steady rhythm. These mitigation efforts were undertaken by local councils and environmental organisations but often with disregard to other areas of the coast managed by different administrations. It was only in 1995 that these areas integrated into a national project. With the UK Government's Shoreline Management Plan the romantic routes of Poole and Christchurch Bay were officially re-cast as Subcell 5F, one of many interconnected subsections that made up the long, eroding coastline of England and Wales.

According to the local Council, nature is, in-part, the villain of this story. Shells, sandy clay, fine grey, white, and yellow silty sands make up the geology of the cliffs and this means they are naturally unstable. Landslides are especially common at the east end of Christchurch Bay where the rocks are most permeable, soaking up rain and sponging groundwater. If we sit back and "allow nature to run its course" then the cliffs erode at an average of 1m a year, as they have done in centuries past. This above-national-average denudation is disturbing, but there are now new threats to deal with. Water has extensive power; the heavier the rain, the wetter the winters, and the higher the seas, the more the cliffs become trapped in a cycle of periodic recession and sudden landslides. Powerful storms and aggressive waves are climate-induced threats that will have serious consequences: the extreme weather of 1974 led to a 5m cliff recession in only four months: there will, of course, be more of this to come.

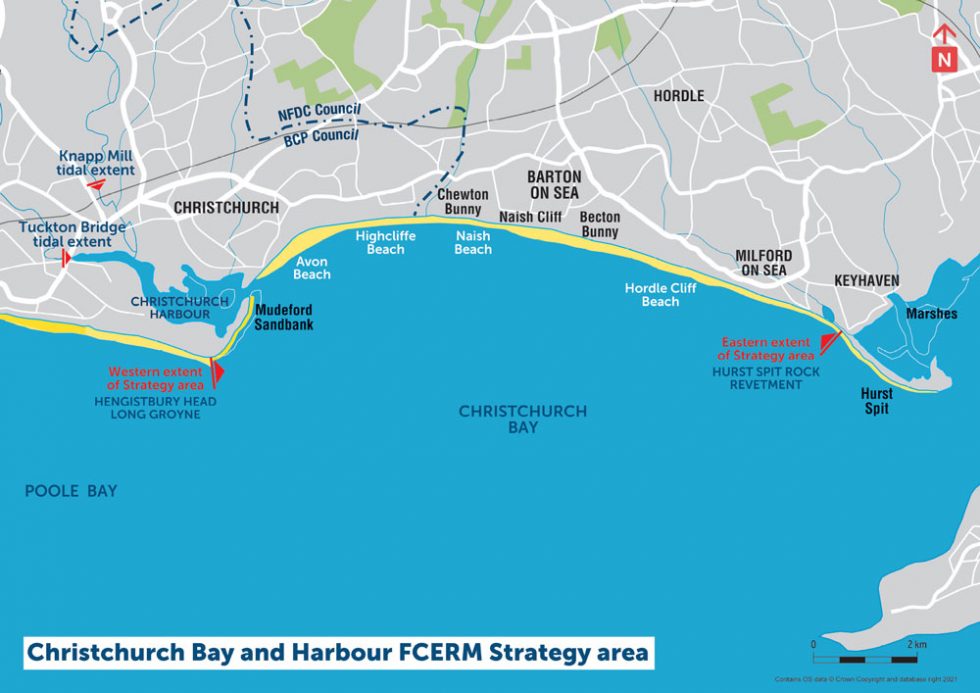

A new hero, the 2023 Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management Strategy, is now expected to prevent nature from running its course by implementing a sustainable management plan over the next 100 years (like most fairy tales, 100 years is the limit to temporal imagination). It will be a joint effort of two town councils and the national Environment Agency, with (it is hoped) an influx of central government funds. Success will be achieved through "managed realignment", in effect, choosing a place on the shore where the cliff-line should be and keeping it there. Yet despite the thread of optimism running through these plans, there is an explicit understanding that there is not much that can be done to prevent the bigger existential threats, and that the cliff will continue to lose its face.

A new hero, the 2023 Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management Strategy, is now expected to prevent nature from running its course by implementing a sustainable management plan over the next 100 years (like most fairy tales, 100 years is the limit to temporal imagination). It will be a joint effort of two town councils and the national Environment Agency, with (it is hoped) an influx of central government funds. Success will be achieved through "managed realignment", in effect, choosing a place on the shore where the cliff-line should be and keeping it there. Yet despite the thread of optimism running through these plans, there is an explicit understanding that there is not much that can be done to prevent the bigger existential threats, and that the cliff will continue to lose its face.

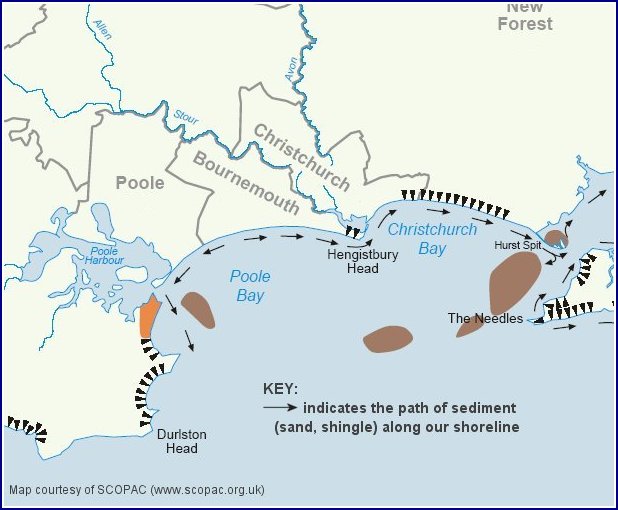

As well as the increased waterpower and extreme weather events caused by anthropogenic climate change, there are also the direct human-made consequences to be considered as these plans are rolled out. Although the cliffs erode fairly evenly across the coast if left untouched, active mitigation in certain areas has meant that whilst some parts of the cliff are strengthened, others are weakened. Attempts to stop the movement of sediment in particular places, such as tourist hotspots of Highcliffe and Barton on Sea beaches, has meant that the natural give-and-take of the whole beach is prevented. These areas have remained somewhat static over the past decade, but down-drift erosion called the Terminal Groynes Effect has occurred in the spaces behind the man-made groynes, creating a laddered set-back effect, and starving the beach of sediment as the coastline moves further east. The mouth of Becton Bunny, for example, has been left without protection, and has eroded far further inland than it would have without human intervention.

These changes are local. For many, they are personal. But they will be played out with familiarity along the national coast: in the UK, which has one of the longest coastlines in Europe, 5.2 million homes are now at risk from flooding and coastal erosion. Give it 100 years, and wonder how many clifftop paths will become invisible.

And yet, there are no real villains here: only things that we can prevent and those we can't. The combined expertise, strategies, and government money are all necessary in protecting homes and lives and memories, but unsteady cliffs have always fallen, the threats are increasing, and there is a point to be made about building houses out of sand.

So, what do we do when familiar paths disappear before our eyes?

I suppose we must forge new ones. Preserve them as best we can. Make them strong for the grandchildren just learning to walk. Teach them to do the same. All the while remembering the paths we have taken and the footprints we have made, especially when they can no longer be seen.

Isobel Akerman

November 2022