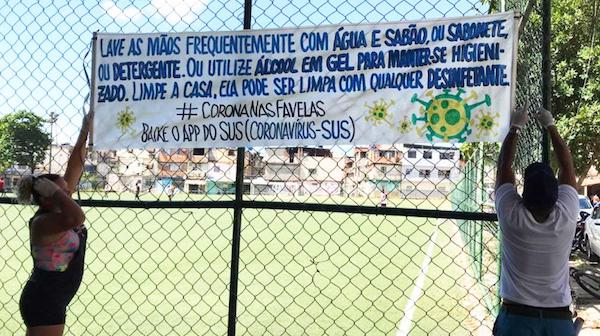

Brazil is home to one of the world’s worst COVID-19 outbreaks, second only to the United States. Journalists, international organizations like the World Health Organization, and social media campaigns like #covidnafavela have documented the high death tolls, the lack of hospital beds, and the struggles of communities without access to life-saving treatments. The images coming from Brazil are harrowing, as an underfunded and overstretched health care system responds to this crisis. But there is another story that can be told here, one that is perhaps not optimistic at the moment, but that can be inspiring for the future. One of the institutions at the heart of Brazil’s response to COVID-19 is the Sistema Único da Saúde (SUS), a publicly-funded health care system that works alongside public research institutes and private hospitals to guarantee free, equitable, and universal health care to all Brazilians. Thirty years ago, the SUS was created during Brazil’s transition to democracy – after 21 years of military dictatorship – thanks to the doctors and public health professionals, pro-democracy social movements, and public at large who all championed health care as an essential human right. The current pandemic has exposed many shortcomings of the SUS, but also all the ways in which this network of health care workers has responded with resilience and commitment. For Brazil, COVID-19 has put the spotlight on the importance of a public health care system. It also offers an unexpected opportunity to reflect on the origins of health care rights in Brazil, and how moments of crisis can sometimes give way to new practices of democracy.

Brazil is home to one of the world’s worst COVID-19 outbreaks, second only to the United States. Journalists, international organizations like the World Health Organization, and social media campaigns like #covidnafavela have documented the high death tolls, the lack of hospital beds, and the struggles of communities without access to life-saving treatments. The images coming from Brazil are harrowing, as an underfunded and overstretched health care system responds to this crisis. But there is another story that can be told here, one that is perhaps not optimistic at the moment, but that can be inspiring for the future. One of the institutions at the heart of Brazil’s response to COVID-19 is the Sistema Único da Saúde (SUS), a publicly-funded health care system that works alongside public research institutes and private hospitals to guarantee free, equitable, and universal health care to all Brazilians. Thirty years ago, the SUS was created during Brazil’s transition to democracy – after 21 years of military dictatorship – thanks to the doctors and public health professionals, pro-democracy social movements, and public at large who all championed health care as an essential human right. The current pandemic has exposed many shortcomings of the SUS, but also all the ways in which this network of health care workers has responded with resilience and commitment. For Brazil, COVID-19 has put the spotlight on the importance of a public health care system. It also offers an unexpected opportunity to reflect on the origins of health care rights in Brazil, and how moments of crisis can sometimes give way to new practices of democracy.

Brazilian citizens have a constitutional right to health care. This right is unambiguously outlined in Article nº196 of Brazil’s 1988 Constitution, which affirms “Health is a right to be enjoyed by all and a duty of the State; it shall be guaranteed by economic and social policies that aim to reduce the risk of disease and other maladies and by universal and equal access to all activities and services for its promotion, protection, and recovery.” This Constitution went beyond the enumeration of rights, to outline how the state would fulfil its new obligations. It announced the creation of the Sistema Único da Saúde (SUS), a free and universal health care system. To some, it might seem odd or excessive to see a Constitution go into such details about policy, and health care policy no less. These are often matters left to legislation, where promises of “universal and equal” have to be moderated or reframed to accommodate more pragmatic outcomes. It is also important to recall that Brazil in the 1980s faced numerous challenges: it needed to design a new political system, while grappling with runaway inflation, high crime rates, rising income inequality, and an external public debt crisis. Why make this the moment to insist on free, equitable, and universal health care?

Brazilian citizens have a constitutional right to health care. This right is unambiguously outlined in Article nº196 of Brazil’s 1988 Constitution, which affirms “Health is a right to be enjoyed by all and a duty of the State; it shall be guaranteed by economic and social policies that aim to reduce the risk of disease and other maladies and by universal and equal access to all activities and services for its promotion, protection, and recovery.” This Constitution went beyond the enumeration of rights, to outline how the state would fulfil its new obligations. It announced the creation of the Sistema Único da Saúde (SUS), a free and universal health care system. To some, it might seem odd or excessive to see a Constitution go into such details about policy, and health care policy no less. These are often matters left to legislation, where promises of “universal and equal” have to be moderated or reframed to accommodate more pragmatic outcomes. It is also important to recall that Brazil in the 1980s faced numerous challenges: it needed to design a new political system, while grappling with runaway inflation, high crime rates, rising income inequality, and an external public debt crisis. Why make this the moment to insist on free, equitable, and universal health care?

The 1988 Constitution culminated Brazil’s transition to democracy. Following the 1964 coup, Brazil endured two decades of repressive military rule. This dictatorship had a legalistic bent: it issued several Institutional Acts and even its own Constitution in 1967 to legalize political purges and curtail most civil rights. Brazil’s new Constitution would need to dismantle those authoritarian institutions, and reverse the ways in which the military’s economic policies had exacerbated socioeconomic and regional inequalities. When the 1988 Constitution was finally promulgated on October 5th, Dr. Ulysses Guimarães, the congressional deputy who had presided over this process, marked the occasion by calling out: “We hate dictatorship. Hate and disgust.”

The 1988 Constitution culminated Brazil’s transition to democracy. Following the 1964 coup, Brazil endured two decades of repressive military rule. This dictatorship had a legalistic bent: it issued several Institutional Acts and even its own Constitution in 1967 to legalize political purges and curtail most civil rights. Brazil’s new Constitution would need to dismantle those authoritarian institutions, and reverse the ways in which the military’s economic policies had exacerbated socioeconomic and regional inequalities. When the 1988 Constitution was finally promulgated on October 5th, Dr. Ulysses Guimarães, the congressional deputy who had presided over this process, marked the occasion by calling out: “We hate dictatorship. Hate and disgust.”

Often called the Citizen Constitution, Brazil’s 1988 Constitution stands as one of the world’s longest constitutions, second only to India, with 250 articles that enumerate an impressive list of civil, political, social, economic, and environmental rights. One reason for its length is that this Constitution had to respond to the demands of different sectors of society.  Formally, the responsibility for drafting the document fell to the National Constituent Assembly (Assembléia Nacional Constituinte or ANC in Portuguese), which deliberated for nearly two years with its 559 elected delegates (only 26 of whom were women), including three of Brazil’s future presidents. In practice, however, much of the work in defining Brazil’s democratic future took place outside the ANC chambers. It depended on popular participation, as social movements, political activists, religious groups, labor organizations, professional associations, and indigenous leadership petitioned for their causes and concerns. This mobilization of civil society was the outgrowth of decades of social protests and pro-democracy movements against the military dictatorship, now being channeled to write a new constitution.

Formally, the responsibility for drafting the document fell to the National Constituent Assembly (Assembléia Nacional Constituinte or ANC in Portuguese), which deliberated for nearly two years with its 559 elected delegates (only 26 of whom were women), including three of Brazil’s future presidents. In practice, however, much of the work in defining Brazil’s democratic future took place outside the ANC chambers. It depended on popular participation, as social movements, political activists, religious groups, labor organizations, professional associations, and indigenous leadership petitioned for their causes and concerns. This mobilization of civil society was the outgrowth of decades of social protests and pro-democracy movements against the military dictatorship, now being channeled to write a new constitution.

Heath care rights became a cornerstone of Brazil’s new democracy. The meaning and content of health care rights, moreover, would not be decided exclusively by jurists, experts, or politicians. The push to make health care an obligation of the state came from civil society, and from the health care sector in particular. These efforts first took shape at the 8ª Conferência Nacional de Saúde in 1986, which drew over 4,000 attendees, with doctors and public health professionals at the forefront of this political project to make health care a fundamental right.  This group worked to give legal shape to health rights, as those gathered approved the first blueprint for the SUS as a universal and free system and drafted several resolutions that ultimately made their way into the Constitution. At the same time, one of the central aims of this meeting was to propose a more ambitious definition for health, one that abandoned the disease-centric approach of prior public health regimes to instead treat health care as a social, economic, and environmental issue. “Health” in legal and policy contexts now encompassed issues like food access and nutrition, housing, education, income, employment and labor conditions, transportation, rest and recreation, the environment, land rights, and access to health care services. The working papers and resolutions approved at this meeting also asserted the importance of community participation in public health initiatives, recognizing that health care could not be solely articulated as individualized care but needed to account for family welfare and the wellbeing of the community.

This group worked to give legal shape to health rights, as those gathered approved the first blueprint for the SUS as a universal and free system and drafted several resolutions that ultimately made their way into the Constitution. At the same time, one of the central aims of this meeting was to propose a more ambitious definition for health, one that abandoned the disease-centric approach of prior public health regimes to instead treat health care as a social, economic, and environmental issue. “Health” in legal and policy contexts now encompassed issues like food access and nutrition, housing, education, income, employment and labor conditions, transportation, rest and recreation, the environment, land rights, and access to health care services. The working papers and resolutions approved at this meeting also asserted the importance of community participation in public health initiatives, recognizing that health care could not be solely articulated as individualized care but needed to account for family welfare and the wellbeing of the community.

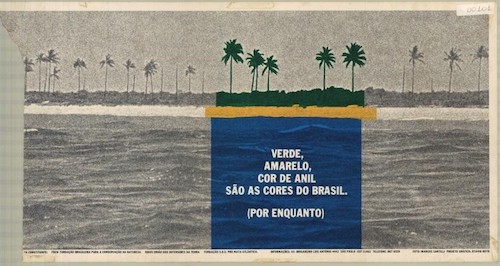

What is remarkable about the health care debates in 1980s Brazil is how these ideas were not only conceived within national congresses and formal political processes, but also in the public sphere and through popular contestation. Women organized their own conference, the Conferência Nacional de Saúde e Direitos da Mulher, advocating for women’s health issues while also pushing for a universal and nationalized system. Newspapers reported on the welfare of Brazilian society, publishing statistics on infant mortality, malaria infection, and malnourishment. These reports documented the impact of income inequality and regional disparities on health outcomes, with one professor of medicine putting the spotlight on the 30-year disparity in life expectancy between someone born in the impoverished Northeast of the country and someone born in the industrialized Southeast region.

What is remarkable about the health care debates in 1980s Brazil is how these ideas were not only conceived within national congresses and formal political processes, but also in the public sphere and through popular contestation. Women organized their own conference, the Conferência Nacional de Saúde e Direitos da Mulher, advocating for women’s health issues while also pushing for a universal and nationalized system. Newspapers reported on the welfare of Brazilian society, publishing statistics on infant mortality, malaria infection, and malnourishment. These reports documented the impact of income inequality and regional disparities on health outcomes, with one professor of medicine putting the spotlight on the 30-year disparity in life expectancy between someone born in the impoverished Northeast of the country and someone born in the industrialized Southeast region.

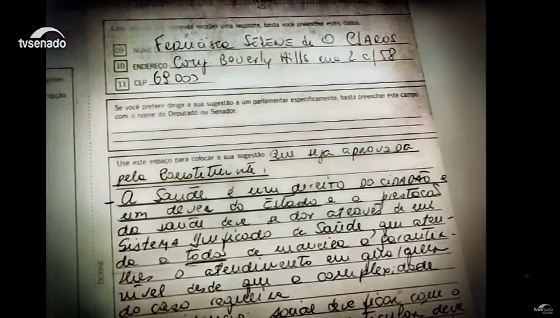

We also have insight into the frustrations and hopes of ordinary citizens thanks to a remarkable letter-writing campaign that unfolded alongside the ANC in which people wrote to their delegates with suggestions for the new Constitution. These letters contain fragments of daily struggles, as people documented how Brazil’s economic crisis had aggravated its health crisis, with the rising cost of living forcing some families to choose between rent and essential medications, or how others lacked access to basic medical attention. Some of these letters beca me the focus of the documentary Cartas ao país dos sonhos [Letters to the country of dreams] produced by Brazil’s government to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the 1988 Constitution. The documentary begins with a nurse from Manaus, reflecting on her “suggestions” to the ANC: “Health is a citizen’s right and the obligation of the State,” she begins, going on to articulate her vision for Brazil’s future health care system, “the provision of health care must take place through a Unified Health Care System, one that serves everyone in a way that guarantees care … for as long as the complexity of the case requires. The community must participate in planning the health sector’s goals and oversee the implementation of health care policy, especially in the uses of public funds so that [these funds] can benefit the people.” Her words echo several articles in the 1988 Constitution and Law Nº8.080 that created the SUS in 1990. They also reveal some of the ways in which constitutional promises have fallen short of practice.

me the focus of the documentary Cartas ao país dos sonhos [Letters to the country of dreams] produced by Brazil’s government to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the 1988 Constitution. The documentary begins with a nurse from Manaus, reflecting on her “suggestions” to the ANC: “Health is a citizen’s right and the obligation of the State,” she begins, going on to articulate her vision for Brazil’s future health care system, “the provision of health care must take place through a Unified Health Care System, one that serves everyone in a way that guarantees care … for as long as the complexity of the case requires. The community must participate in planning the health sector’s goals and oversee the implementation of health care policy, especially in the uses of public funds so that [these funds] can benefit the people.” Her words echo several articles in the 1988 Constitution and Law Nº8.080 that created the SUS in 1990. They also reveal some of the ways in which constitutional promises have fallen short of practice.

It is worth noting that the 1988 Constitution was not the first to enumerate social and economic rights in Brazil, nor the only one to mention public health as the responsibility of government. Some version of these rights had appeared in Brazil’s 1934 Constitution (and in the three constitutions that followed, including the two written for dictatorships). But those prior constitutions did not guarantee universal suffrage, and they placed conditions or restrictions on the exercise of individual and social rights. Similarly, Brazil’s health care system prior to the SUS was a public system, but not a universal one. Starting in the 1930s, Brazil’s government had created a network of social security funds (Institutos de Aposentadoria e Pensões, IAPS), which were differentiated according to profession, in a syndicalist-corporatist framework. This system was expanded and reformed over the next fifty-plus years, but it remained tied to profession, to the exclusion of rural workers, domestic workers, informal labor, and others. Those not covered by this system were designated indigentes, and had to rely on charity health services. The 1988 Constitution thus did away with the ways in which citizenship had previously been stratified in Brazil, with its insistence that socioeconomic rights would be equally enjoyed, independent of race, class, gender, or profession. This Constitution also became the first to acknowledge long-standing racial, socioeconomic, and regional inequalities in Brazil, and the first to commit to reducing these inequalities and eradicating poverty. Free and universal health care became not only an individual right, but a strategy for dealing with structural inequalities.

The SUS today guarantees coverage for all residents in Brazil, with about 70% of the population relying exclusively on its services. Brazil has a two-tiered system in which those who can afford it purchase private insurance plans. The SUS is unified but highly decentralized, with its various responsibilities divided between federal, state, and municipal levels of service. One of its accomplishments is the Programa de Saúde de Família (Program for Family Health, PSF),  created in 1994 to provide primary care, dentistry, vaccinations, and medications for some of Brazil’s poorest and most isolated communities. This unit leads Brazil’s vaccination efforts, as the SUS oversees one of the world’s largest vaccination programs in the world, combating more than 19 infectious diseases. The Programa de Saúde de Família innovates with its emphasis on families, instead of its individuals, as well as in its employment not only of doctors and nurses, but also of community health agents in order to strengthen links between the community and health services. Today, this program oversees over 40,000 PSF teams, with more than 265,000 community health care workers. This community health infrastructure is part of the reason why Brazil has been able to implement innovative and successful strategies in dealing with various epidemics and infectious diseases, like HIV/AIDS and Zika.

created in 1994 to provide primary care, dentistry, vaccinations, and medications for some of Brazil’s poorest and most isolated communities. This unit leads Brazil’s vaccination efforts, as the SUS oversees one of the world’s largest vaccination programs in the world, combating more than 19 infectious diseases. The Programa de Saúde de Família innovates with its emphasis on families, instead of its individuals, as well as in its employment not only of doctors and nurses, but also of community health agents in order to strengthen links between the community and health services. Today, this program oversees over 40,000 PSF teams, with more than 265,000 community health care workers. This community health infrastructure is part of the reason why Brazil has been able to implement innovative and successful strategies in dealing with various epidemics and infectious diseases, like HIV/AIDS and Zika.

One of the by-products of Brazil’s advancements in public health in the 1990s and 2000s was that it turned some of the lessons it had learned at home into global public health advocacy. By the early 2000s, Brazil had taken the lead in South-South cooperation, with initiatives in countries across the Global South, especially in the Caribbean and South America and in Africa through its ties to the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP). Under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2011), this push for greater South-South cooperation was motivated by a renewed sense of solidarity between Brazil and other Global South nations. By sidestepping the colonial power relations that had framed prior international development initiatives, Brazil’s government attempted a more democratic and collaborative approach. For Brazil, the early 2000s were a moment of optimism: its economy was growing, its currency stable, and it had managed to dramatically reduce hunger and poverty. Its leaders looked at these successes as proof that Brazil could become a major economic powerhouse and a leader in global public health.

Brazil embraced multiple development strategies to share the lessons that it had learned at home in poverty eradication and public health with other low-and-middle-income countries. Public health institutes like Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz) led the way in sharing technical expertise and in training local public health officials. While North-South development aid programs tended to emphasize the passive transfer of knowledge and technology, Brazil’s approach centered on building local capacity through teacher training and institutional support. Fiocruz, for example, created graduate public health programs in Angola and led Brazil’s humanitarian response in Haiti following the 2010 earthquake. Brazil also financed the building of a pharmaceutical plant in Mozambique, opened in 2012 to reduce the country’s dependence on foreign drug donors, especially for drugs treating HIV/AIDS. These efforts continue today, as Fiocruz committed in March 2020 to sending a team of epidemiologists and public health professionals to Portuguese-speaking countries in Africa to support local responses to COVID-19. These South-South initiatives are not without critics, as some question how effective these efforts have been, and others ask whether they are ultimately designed in service of trade and private investments. The future of South-South cooperation, moreover, is uncertain, as recent governments have shifted away from development grants to emphasize commercial and industrial interests, especially in Africa.

Brazil’s 1988 Constitution is not perfect, nor is the public health system it created. Today, the SUS is overstretched and underfunded, and it does not have enough doctors to service the public, especially marginalized communities. The public faces long waits for certain treatments, a shortage of hospital beds, and lack of access to essential medications. The strain on services has become more acute in recent years. In 2016, the National Congress approved a constitutional amendment that limited public expenditures on health and education for the next twenty years.

COVID-19 thus arrived at a moment when SUS and other public health initiatives were already feeling the strain of austerity and pushes for more privatization. The challenges now facing Brazil’s public health system extend beyond the lack of resources, as countless reports in recent months document the lack of hospital beds and ventilators in certain parts of the country, not to mention the corruption allegations pointing to the misuse of public funds and overpricing schemes. Beyond these concerns, Brazil’s response to COVID-19 has been impaired by the lack of public health governance at the federal level, as state and local officials are left to tackle a global pandemic without much in the way of national coordination.

COVID-19 thus arrived at a moment when SUS and other public health initiatives were already feeling the strain of austerity and pushes for more privatization. The challenges now facing Brazil’s public health system extend beyond the lack of resources, as countless reports in recent months document the lack of hospital beds and ventilators in certain parts of the country, not to mention the corruption allegations pointing to the misuse of public funds and overpricing schemes. Beyond these concerns, Brazil’s response to COVID-19 has been impaired by the lack of public health governance at the federal level, as state and local officials are left to tackle a global pandemic without much in the way of national coordination.

But the SUS was also designed to be robust, and to emphasize community-based health care. As coronavirus cases surge in Brazil, SUS community health workers pay regular visits to homes, educating families on the virus and preventive social distancing measures, while also helping with testing and tracing. During the ongoing health crisis, this spirit of community-based care has expanded beyond formal channels, as NGOs, community activists, and mutual aid networks have stepped in to fill the gap left by insufficient public resources, especially in poor and marginalized communities. In the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, for example, mutual aid networks are on the frontlines of coordinating essential services during this crisis: distributing water, soap, hand sanitizer, organizing food distribution, and transporting individuals with severe cases to hospitals. These services have proved essential, but not sufficient. COVID-19 has once again put SUS in the spotlight: we can see its shortcomings, but also how it has effectively responded to a health care emergency. Many in Brazil recognize how much worse things could be without it. Here, we can recall the nurse from Manaus and her reflections on the SUS twenty years following its creation: “It’s happening [but] there’s still a lot to do.”

At a moment when there are so many reasons to be pessimistic about the future, it is all the more important to recover past aspirations. One critique often posed to Brazil’s Constitution is that it promised a lot on paper, but many of its commitments to social justice remain unfulfilled or ignored. Brazil remains one of the most unequal societies in the world, with approximately 13.5 million people living in extreme poverty, a figure that has been increasing since 2014, erasing the gains of anti-poverty measures in the early 2000s. The 1988 Constitution, however, is not a lesson in how a constitution can fix social and economic problems. Rather, it is a reminder of the generative power of crises. In the late 1980s, Brazil was transitioning out of a deeply repressive 21-year military dictatorship, with sky-rocketing inflation and a public debt crisis. And yet this became the moment to guarantee free and universal health care. Thanks to this conjuncture, health care rights have become an essential part of Brazil’s new democracy, and for many, its greatest success.

In recent months, we have seen governments worldwide respond to COVID-19 with a sense of urgency, as people have sacrificed some of their individual freedoms for the wellbeing of the community. Some have asked what it might look like if this same sense of urgency for collective action were mobilized to address climate change. We are coming to terms with how COVID-19 cannot be separated from environmental catastrophe, just as it cannot be divorced from problems of social inequality, racial injustice, and economic depression. In reading about Brazil’s 1988 Constitution in this context, what struck me immediately was not just the enthusiasm for health care as a human right. Rather, it was the ways in which this right to health was articulated alongside environmental rights. The sub-commissions and commissions that wrote the Constitution grouped health rights with environmental rights. To some, this might be a mere bureaucratic accident. But to the doctors and public health professionals who were on the frontlines, advocating for a free and universal health care system, it seemed obvious that health care rights needed to be understood in terms of whatever a person needed to live a healthy life. How could this not include considerations of sanitation, air quality, and access to water? In this spirit, Article Nº200 of the 1988 Constitution outlined that the SUS would be responsible for, among other things, “collaboration in the protection of the environment.” Echoes of this idea appeared in medical reports and policy memos at the time, underscoring the push in Brazil for a shift from disease-focused medicine to a health care system that addressed the socioeconomic and environmental factors that impact public health outcomes. Now might be the time to return to this expansive understanding of health, so that the COVID-19 crisis might once more lead to the coupling of public health and climate change debates.

In recent months, we have seen governments worldwide respond to COVID-19 with a sense of urgency, as people have sacrificed some of their individual freedoms for the wellbeing of the community. Some have asked what it might look like if this same sense of urgency for collective action were mobilized to address climate change. We are coming to terms with how COVID-19 cannot be separated from environmental catastrophe, just as it cannot be divorced from problems of social inequality, racial injustice, and economic depression. In reading about Brazil’s 1988 Constitution in this context, what struck me immediately was not just the enthusiasm for health care as a human right. Rather, it was the ways in which this right to health was articulated alongside environmental rights. The sub-commissions and commissions that wrote the Constitution grouped health rights with environmental rights. To some, this might be a mere bureaucratic accident. But to the doctors and public health professionals who were on the frontlines, advocating for a free and universal health care system, it seemed obvious that health care rights needed to be understood in terms of whatever a person needed to live a healthy life. How could this not include considerations of sanitation, air quality, and access to water? In this spirit, Article Nº200 of the 1988 Constitution outlined that the SUS would be responsible for, among other things, “collaboration in the protection of the environment.” Echoes of this idea appeared in medical reports and policy memos at the time, underscoring the push in Brazil for a shift from disease-focused medicine to a health care system that addressed the socioeconomic and environmental factors that impact public health outcomes. Now might be the time to return to this expansive understanding of health, so that the COVID-19 crisis might once more lead to the coupling of public health and climate change debates.

Melissa Teixeira is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania

She would like to thank Rodrigo Veiga da Cunha, UPenn (Class of 2023), for assistance in researching this piece