Tiree / Tiriodh

I have never been to Tiree. Yet I am of Tiree.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. I had booked what I hoped to be the first of many visits in March 2020. Then came the pandemic. The lockdown was imposed the very week I was to take the long train journey from southern England to Glasgow, and the hour-long flight into Tiree’s airstrip. But it was already clear some time before that to travel wouldn’t be showing due care to myself, to my family, or to the islanders.

It is nearly a century and a half since my great-grandmother took the boat the other way from Tiree to Glasgow. Catherine Campbell. Or so says all the paperwork that documents her life. Like all the people of Tiree, or Tiriodh, she lived in another tongue, the Gaelic. Caitrìona Caimbeul. There was no Catherine in Tiree, nor her father Charles, or her grandfather Donald, or her grandmother Christina MacDonald. These words were a copperplate-handed obeisance to the higher orders in the kirk’s registers and the ledgers of landlord’s Factor, his rent-collector. Dutifully or passionately drawing to the Sunday sermon at Heylipol, or grafting to limit the rental arrears, there was Seàrlas, and Dòmhnall, and Ciorstaidh (pronounced something like ‘Kirsty’) Dòmhnallach.

It is nearly a century and a half since my great-grandmother took the boat the other way from Tiree to Glasgow. Catherine Campbell. Or so says all the paperwork that documents her life. Like all the people of Tiree, or Tiriodh, she lived in another tongue, the Gaelic. Caitrìona Caimbeul. There was no Catherine in Tiree, nor her father Charles, or her grandfather Donald, or her grandmother Christina MacDonald. These words were a copperplate-handed obeisance to the higher orders in the kirk’s registers and the ledgers of landlord’s Factor, his rent-collector. Dutifully or passionately drawing to the Sunday sermon at Heylipol, or grafting to limit the rental arrears, there was Seàrlas, and Dòmhnall, and Ciorstaidh (pronounced something like ‘Kirsty’) Dòmhnallach.

To make sense of their lives we must try to know them as they knew themselves. Muireach Caimbeul, in his mid-40s, would sit on a pew listening to the sermon in 1764, when the island was visited by Rev John Walker, later to be Professor of Natural History at Edinburgh, and future Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. There he found ‘not above twenty persons in the parish who can understand a sermon [in English].’ About 1 600 people lived on the island. As late as the 1880s, all but two tenants, in the words of their landlord the 8th Duke of Argyll ‘are, without exception, Highlanders speaking Gaelic.’

Caitrìona left around 1880. My grandmother was born in 1911, a late last child in a long line. Then came the pandemic. Caitrìona was taken in the first wave of influenza in 1918, and the family’s connection to the island largely severed. This is thin gruel to be of Tiree, surely? Tha mo cheann na bhrochan. But here I am, working on the history of Tiree after all. I will try and make some sense of it.

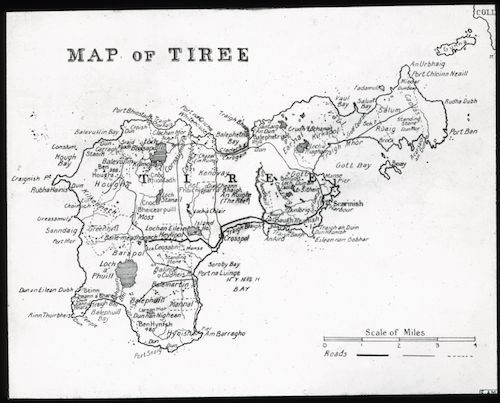

Tiree is the westernmost of the Inner Hebrides, lying across twenty miles of open sea from Mull. Although to the north-west lie the rock- and peatlands of Barra and the Uists in the outer isles, west of Tiree is nothing but two thousand miles of rolling ocean. The island is twelve miles long and three miles wide, narrowing towards its eastern end, with a coast of broad creamy beaches interspersed with rocky shorelines and no natural harbours. Weather tends not to linger, and Tiree has a rare claim to fame in the Scottish west for sunshine. Yet with only two low hills the whole isle is exposed to keen and piercing winter and spring winds, and can be blasted by the first landfall of violent oceanic storms that cut it off for days or weeks and deluge the land with sleety rain. Although snow lies but briefly, the growing and outdoors season is short and the sandy soils and boggy hollows of the land prone to both summer drought and swift waterlogging.

Yet during the height of summer, its sandy pastures blossom with clovers; with sea campion, sea gillyflower, sea rocket, bloody cranesbill, and more, ‘a most beautiful embroidered carpet.’ Skylarks sing and rise in profusion. Wild duck, cranes, curlews, grey and green plover, pigeons, and snipes make permanent homes, although already reduced in number by the early nineteenth century. In the summer pasturing livestock mixed with immense flocks of lapwings. The islanders grew local varieties of oats and barley, with a greater share of the soft inclines and plains of Tiree tilled than in any other Scottish island. From the middle of the eighteenth century, potatoes became increasingly important in the diet. The fields were piled with swards of seaweed lifted in carts and baskets from the shoreline by hundreds of small, hardy ponies later exported and bred for mine-work.

Yet during the height of summer, its sandy pastures blossom with clovers; with sea campion, sea gillyflower, sea rocket, bloody cranesbill, and more, ‘a most beautiful embroidered carpet.’ Skylarks sing and rise in profusion. Wild duck, cranes, curlews, grey and green plover, pigeons, and snipes make permanent homes, although already reduced in number by the early nineteenth century. In the summer pasturing livestock mixed with immense flocks of lapwings. The islanders grew local varieties of oats and barley, with a greater share of the soft inclines and plains of Tiree tilled than in any other Scottish island. From the middle of the eighteenth century, potatoes became increasingly important in the diet. The fields were piled with swards of seaweed lifted in carts and baskets from the shoreline by hundreds of small, hardy ponies later exported and bred for mine-work.

To John Walker, the people of Tiree were a tribe out of time, barely changed since their ancestors brought the Gaelic tongue at the twilight of the Roman Empire. As he toured the islands plans were being laid for the enlightened squares and promenades of Edinburgh’s New Town. Glasgow was rising to be the tobacco emporium of the world, and the British Empire wrestled with France for supremacy in North America and Bengal. In those same years James MacPherson was beginning to publish his poems of Ossian and the Fianna – stories familiar among the islanders – a concocted, alleged rediscovery of ancient epics that would fire a wave of romantic adulation for the timeless virtues of the Gael – albeit generally from a distance.

In truth, the triumvirate which ruled a suposedly traditional life - grain, those American potatoes and seaweed - would drive a series of violent surging storms across Tiree for a century. In their wake, the great majority of descendants of the fifteen hundred who lived on the island in 1750 were scattered afar across the old dominions of the Empire. Tiriodh, after all, was less than three hundred miles from Manchester. But despite such proximity, in global terms, it was not in the calm eye of the industrial storm. It would be blasted by revolution as surely as by a March gale.

Nor had Tiriodh’s isolation ever been complete. Smallpox made episodic and brutal visitations, allegedly killing over 100 infants in 1756. Young men were siphoned off to imperial wars. By the time of the American Revolution, there were 2 000 islanders. When Britain plunged into war against revolutionary France, smallpox had been banished by inoculation and there were five hundred more. The first census of 1831 recorded – certainly an underestimate – three times as many as had lived on Tiree in 1750. Yet within twenty years the population fell into as yet unreversed decline.

![View from Beinn Hough

Looking north-east from the summit of Beinn Hough over the flat, well-farmed interior of the Isle of Tiree. The large loch is Loch Bhasapoll NL9746. The Isle of Coll can be seen on the skyline.

Creative Commons Licence [Some Rights Reserved] © Copyright Oliver Dixon and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence. View from Beinn Hough

Looking north-east from the summit of Beinn Hough over the flat, well-farmed interior of the Isle of Tiree. The large loch is Loch Bhasapoll NL9746. The Isle of Coll can be seen on the skyline.

Creative Commons Licence [Some Rights Reserved] © Copyright Oliver Dixon and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.](tiree_images/3.jpg)

Clergy, often sympathetic observers of their neighbours, would consider the island’s people, ‘industrious, and chearful, and often engaged in active employments.’ Yet according to the instructions sent out by the 5th Argyll in November 1802, there was already a fundamental problem with these people, proliferating in number since smallpox abated. There were just too many of them.

‘As so many evils spring from the overstock of population on the island, and must year after year grow more and more, till at last the burden must become insupportable, it is a subject of importance to consider how a remedy can be applied to its relief. The distance from market, the scarcity of fuel, and the general inconveniences attending an insular situation, are not favourable to invite men of speculation and prosperity to begin any branch of manufactures that might give employment to the supernumerary stock of men, women & children, & lead them through a conviction of interest to habits of industry out of their present laziness and idleness.’

These comments provide a fair list of the disadvantages faced by Tiree, remote from an ‘improving’ and commercial economy, and crucially the economy in which the island’s landlord dwelt and spent in his wealth. Yet despite these clear structural impediments, we will see time and time again the poverty of the islanders blamed on an apathetic reluctance to arise from the bed made over one and a half millennia before. The stories presented here will show how unfair that accusation was, but how, for all that, so many of those of Tiree would end up blown to all the corners of the Earth, some filling their sails with hope and eventually lucre. Others but the chaff blown onto the sandy machair when the winnowing farmers tossed the grains into the air.

| The Colony » |