In 1833, while visiting Lebanon ’s high mountains, the Orientalist French poet Alphonse de Lamartine became captivated by the country’s cedar trees. The cedars, he wrote, “know the history of the earth better than history itself.” Considered sacred by local religious sects, the trees reach heights up to 115 feet, diameters of 40 feet, and can exceed one thousand years of age.

Two centuries after Lamartine’s voyage, the iconic cedars are under dire threat. As temperatures rise, cedrus libani no longer thrives in its ecological niche of 4600-6500 feet above sea level. Nine of the twelve existing cedar forests are already located upon summits; only three forests may escape heat by migrating higher. Wildfires hit record altitudes in 2020. A native sawfly infestation is decimating cedar buds in the Tannourine forest. By 2100, only a few cedar forests may remain in a small northern section of Mount Lebanon.

Fear of losing the cedars is not unprecedented. As early as 1570, German traveler Leonhart Rauwolff wrote about the Bcharre forest: “Although this hill hath, in former ages, been quite covered with cedars, yet they are since so decreased.” Even Lamartine, during his 1833 visit, wrote that the cedars diminished in numbers every century. He lamented that long ago, ( “jadis”) voyagers counted forty cedars in Ehden, while he counted only seven. A century and a half later, the same view held. In 1978, an Economic Botany article claimed that early exploitation of the cedars has “left only scattered groves today.”

Historical testimonies about the cedars of Lebanon place an overwhelming emphasis on loss. But not all claims about the cedars’ systemic deforestation can be trusted.

Historical testimonies about the cedars of Lebanon place an overwhelming emphasis on loss. But not all claims about the cedars’ systemic deforestation can be trusted.

Historian and archeologist Romana Harfouche considers the discourse about cedrus libani ’s deforestation to be catastrophist, likely rooted in the narrative of “environmental declinism,” a colonial myth that originated in the nineteenth century as the French invaded Algeria and Morocco. As historian Diana Davis has shown, environmental declinism was inspired by an early-seventeenth century biblically-derived geological theory developed by the Irish Archbishop James Ussher. According to Ussher’s theory, though the Earth was luscious and green when created by God in 4004 BC, it progressively deteriorated as human immorality and sin caused fertile land to become barren. Binding natural landscapes to their subjective morality, Anglo-European colonists came to perceive lush, forested environments as Christian and Western, and deserts as formed under “heathen” Muslim and Arab stewardship. In North Africa and the Middle East, European colonizers accused nomadic Muslim and pagan Arab societies of straying from the settled agriculture of the Romans and Greeks. Propagation of this racialist narrative partly justified imperial encroachment into the Middle East in the name of environmental “improvement” and restoration to an imagined ancient green glory. Harfouche suggests that nineteenth century environmental declinism, exacerbated by the famous cedar ’s overrepresentation in discourse (compared to the oak and pine), created the “catastrophist deforestation narrative” that has been promulgated for centuries.

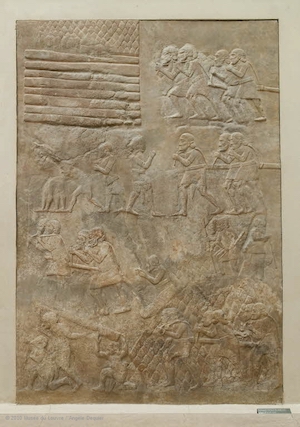

However, as shown by Rauwolff ’s sixteenth century testimony, the deforestation narrative existed well before European colonization. Rauwolff may have been relating knowledge expressed by his local Maronite Christian guides, or he may have believed that demand for cedar wood by ancient Empires—which used the fragrant, durable material to build temples and boats—deforested Lebanon well before the first millennium. Historian Françoise Briquel Chatonnet challenges the idea of “ancient deforestation:” the abundance of ancient frescoes and writings about the cedar ’s timber trade, she states, created the illusion of heavy exploitation. Due to rudimentary felling techniques and limited long-distance boating, cedar wood quantities were likely small and rare. Scientific research seems to corroborate such an assessment. A 2008 palynological study concluded that deforestation of Mount Lebanon occurred during the Neolithic but stopped during the Bronze Age. Their findings challenge earlier claims that the ancient Egyptians deforested the Barouk forest on Mount Lebanon later, during the Iron Age.

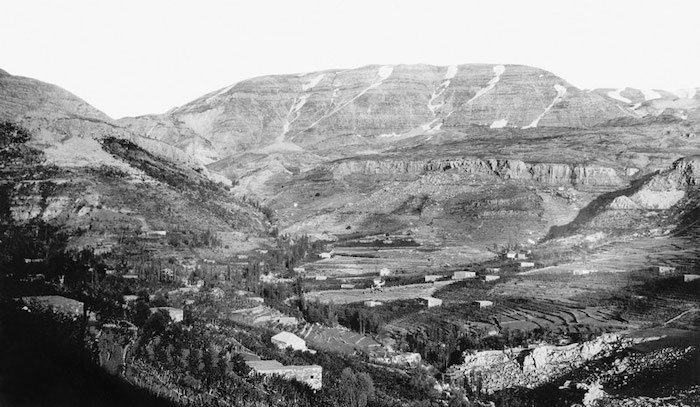

No consensus prevails regarding the pre-anthropic state of Lebanon ’s cedar populations, nor on patterns and perpetrators of deforestation. We know that as pilgrimages to the cedars of Mount Lebanon increased in the 16th century, the Maronite Church issued an edict threatening excommunication to whomever injured the trees. In spite of this, according to Harfouche, the primary deforestation of Lebanese mountain forests began with the development of Christian mountain villages in the 19th century. And according to human geographer Marvin Mikesell, Maronite Christian and Druze peasants depleted cedar and fir populations by turning forest canopies on slanted mountain slopes into terraces for cultivation. So while authorities like the Maronite Church may have imagined a long-term plan for preserving the cedars, the decentralized nature of feudal Mount Lebanon under Ottoman rule likely allowed cultivators and farmers to remove cedars without consequence.

No consensus prevails regarding the pre-anthropic state of Lebanon ’s cedar populations, nor on patterns and perpetrators of deforestation. We know that as pilgrimages to the cedars of Mount Lebanon increased in the 16th century, the Maronite Church issued an edict threatening excommunication to whomever injured the trees. In spite of this, according to Harfouche, the primary deforestation of Lebanese mountain forests began with the development of Christian mountain villages in the 19th century. And according to human geographer Marvin Mikesell, Maronite Christian and Druze peasants depleted cedar and fir populations by turning forest canopies on slanted mountain slopes into terraces for cultivation. So while authorities like the Maronite Church may have imagined a long-term plan for preserving the cedars, the decentralized nature of feudal Mount Lebanon under Ottoman rule likely allowed cultivators and farmers to remove cedars without consequence.

It is worth noting that while European colonists blamed Arab nomadic populations for desertifying land, they praised the beneficial effect of sedentary agriculture, which connoted a “civilized” Judeo-Christian way of life. In Lebanon, ironically, the agricultural practices they believed would restore a “degraded” environment ’s Edenic glory may have in fact been the root cause of deforestation, as Christian and Druze peasants cleared forests for crops.

In the past, losing a cedar meant losing commercial, military, religious, or aesthetic value. Today, in the midst of a worsening climate crisis, the loss of the cedar inscribes itself into the earth ’s ongoing collapse of biodiversity. Our conception of loss has changed; today, nobody would dare put an axe to a protected cedar, but the trees have never been so vulnerable.

In the past, losing a cedar meant losing commercial, military, religious, or aesthetic value. Today, in the midst of a worsening climate crisis, the loss of the cedar inscribes itself into the earth ’s ongoing collapse of biodiversity. Our conception of loss has changed; today, nobody would dare put an axe to a protected cedar, but the trees have never been so vulnerable.

Looking forward, a holistic understanding of the cedar’s deforestation will be built upon multiple types of knowledge—testimonial, aesthetic, architectural, archeological, scientific. The ancient tree’s story cannot be written in one day. But if the cedar knows the earth’s history, we can only hope to access its secrets. Doing so calls for engaging with a patchwork of knowledge systems— peer-reviewed consensus-based science and resource management, but also historical religious worship, indigenous stewardship, and oral tradition. Perhaps by approaching the cedars from these many perspectives, we may access the archives within the trees.