The coronavirus pandemic has stretched the United States’ meat supply to the breaking point. In early April, meat-processing facilities across the country were facing outbreaks among their workers. Smithfield announced on April 12 that it had to shutter its Sioux Falls, South Dakota plant, which accounts for as much as 5% of US pork production. A few days later, Tyson Foods, one of the largest meat processors in the world, ran full page ads in the Wall Street Journal and New York Times arguing “the food supply chain is breaking.” Nebraska’s governor Pete Ricketts warned that "it's vitally important that we keep our food processors open and do everything we can to ensure the supply chain, because we would have civil unrest if that was not the case.” On April 28, President Trump invoked the Defense Production Act, deeming meat processing “critical infrastructure” and pledging to use federal power to keep facilities running. Production has since started to rebound, but worker infection rates and fatalities continue to increase. As of early June, there have been more than 20,000 cases of coronavirus at more than 200 plants in 33 states. More than 70 people have died.

The coronavirus pandemic has stretched the United States’ meat supply to the breaking point. In early April, meat-processing facilities across the country were facing outbreaks among their workers. Smithfield announced on April 12 that it had to shutter its Sioux Falls, South Dakota plant, which accounts for as much as 5% of US pork production. A few days later, Tyson Foods, one of the largest meat processors in the world, ran full page ads in the Wall Street Journal and New York Times arguing “the food supply chain is breaking.” Nebraska’s governor Pete Ricketts warned that "it's vitally important that we keep our food processors open and do everything we can to ensure the supply chain, because we would have civil unrest if that was not the case.” On April 28, President Trump invoked the Defense Production Act, deeming meat processing “critical infrastructure” and pledging to use federal power to keep facilities running. Production has since started to rebound, but worker infection rates and fatalities continue to increase. As of early June, there have been more than 20,000 cases of coronavirus at more than 200 plants in 33 states. More than 70 people have died.

Crises not only reconfigure existing relationships and processes, they also bring existing dynamics into sharper relief. The coronavirus crisis in the nation’s meat plants has underscored the importance of meat to American prosperity. If hungry Americans found grocery aisles bare, it would personalize the pandemic and undermine the president’s case that life is returning to normal. As a result, coronavirus outbreaks among workers have not been considered an inherent problem, but rather a threat to the American consumer.

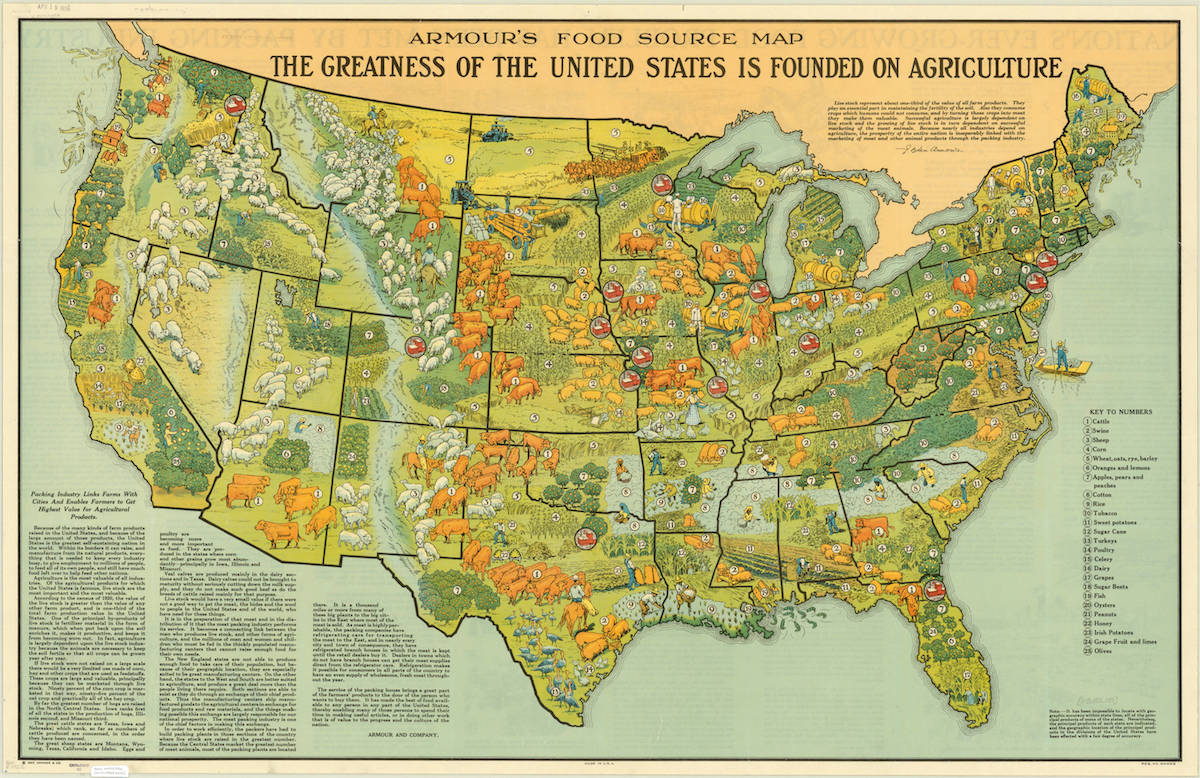

In the United States, meat was not really “essential,” by which I mean not only a widely accepted dietary staple, but also a key feature of self-identity, until the late 19th century. A variety of environmental, political, and economic factors drove this development. In terms of meat processing, a system of centralized mass-slaughter headquartered in Chicago brought meat to the “common laborer” through a combination of innovation—new refrigeration technology and the (dis)assembly line—and exploitation—cut-throat business practices to bankrupt butchers and weaken ranchers. These developments made meat cheaper and expanded the quantity of meat available to supply the nation’s swelling cities.

For late nineteenth century immigrants to the United States, the availability of beef and pork was an indication of newfound prosperity—meats that they may only have had on feast days now became commonplace. Similarly, for the American worker, the ability to afford a steak became a marker of success. This worried home economists, who, concerned about food costs, began studying working-class diets to understand why American workers could not survive on potatoes or rice, as they argued the Irish and Chinese could do. Such anxiety only provided poorer Americans with further evidence of meat’s importance. Taste and nutrition certainly mattered, but meat was essential because its consumption was key to establishing what it meant to be successful in America.

This made meat’s availability a political question. When critics of the new production regime—mostly struggling ranchers and butchers—called for reform, they faced the impossible task of proposing changes that would not threaten beef’s affordability for Americans to keep meat on their tables. Meat had to be cheap and abundant and the Chicago meatpackers had the only model for ensuring that would be the case. Essential, then, in many ways meant politically essential.

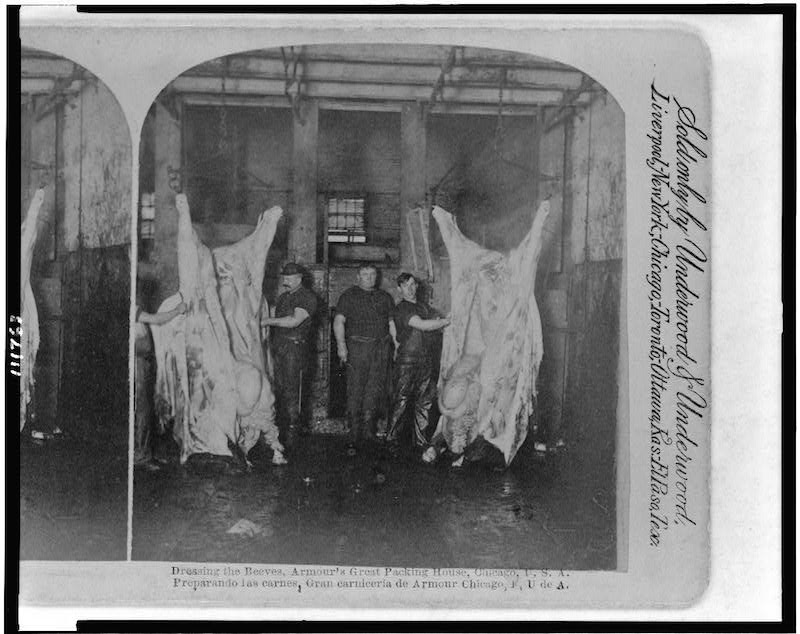

As with many commodities, industrial meat depended on organizational and technological innovations—specialized processing tools, the division of labor, worker synchronization, and more—that increased both worker productivity and worker exploitation. The artisanal process of slaughtering and processing an animal was divided into dozens of small tasks. Workers could then be rapidly trained as well as poorly paid and overworked. Highly-skilled butchers had become replaceable workers. A few high-skilled jobs remained for which employees were paid handsomely, but the average labor cost dropped and processing speed increased dramatically. An artisanal butcher might only process a couple of cattle a day, but in these new facilities, a team of two hundred people could process more than a hundred animals every hour. Further, this new approach required workers to synchronize their work, allowing for additional tactics to increase line speeds, such as paying a small number of “pace-setters” a bonus to work faster and thereby put pressure on the entire team. Though pioneered in the 19th century, the industry works similarly today. Human labor remains more important in meat processing than in other industries; processing is relatively resistant to automation, as the inputs—animal carcasses—vary in size and shape, making human flexibility particularly valuable.

As with many commodities, industrial meat depended on organizational and technological innovations—specialized processing tools, the division of labor, worker synchronization, and more—that increased both worker productivity and worker exploitation. The artisanal process of slaughtering and processing an animal was divided into dozens of small tasks. Workers could then be rapidly trained as well as poorly paid and overworked. Highly-skilled butchers had become replaceable workers. A few high-skilled jobs remained for which employees were paid handsomely, but the average labor cost dropped and processing speed increased dramatically. An artisanal butcher might only process a couple of cattle a day, but in these new facilities, a team of two hundred people could process more than a hundred animals every hour. Further, this new approach required workers to synchronize their work, allowing for additional tactics to increase line speeds, such as paying a small number of “pace-setters” a bonus to work faster and thereby put pressure on the entire team. Though pioneered in the 19th century, the industry works similarly today. Human labor remains more important in meat processing than in other industries; processing is relatively resistant to automation, as the inputs—animal carcasses—vary in size and shape, making human flexibility particularly valuable.

Meatpacking was not only a low-paid and difficult job, but a dangerous one. Workers risked acute injury—death or disablement—as well as chronic conditions like carpal tunnel syndrome that were once associated more with the cleaver than the keyboard. Though life-threatening injuries have declined dramatically since the industry’s origins, injuries in general, and chronic conditions in particular, remain a serious problem.

In the more than a century since the initial creation of this approach to meatpacking, the model’s underlying logic has remained the same, despite temporary shifts in industrial relations and some changes in the production model. Though the nineteenth-century Chicago meatpackers were hostile to unions, by the mid twentieth century, unions like the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA) made meatpacking a better-paid if still gruelling job. It was not work that most Americans could do or would be willing to do, but one could earn a decent living. But starting in the 1960s, a new set of companies like Iowa Beef Processors (IBP) used trucking and the superhighway system to move processing from urban centers to the rural places where animals were raised. These processors also started producing retail-ready products; companies like IBP pioneered “boxed beef,” which was essentially ready for grocery store shelves, rather than producing the large cuts the traditional meatpackers had distributed to retail butchers. These facilities still relied on large amounts of human labor, but the new rural locations did not have the organizing tradition of places like Chicago.

As a result, processing companies brought back the strategy pioneered during the earliest days of meatpacking: recruit workers from vulnerable populations and push them harder and harder. Increasingly, meat processors employed immigrants from Latin America, many of whom were undocumented. Companies also began to employee refugees, including from Southeast Asia and Sudan. In the poultry industry, there have even been cases of processors employing prison labor. All of these populations would face difficulties organizing as well as fear of asserting their legal rights. This tactic of drawing from vulnerable populations, as well as the underlying difficulty of meat processing work, means that meatpacking has one of the highest turnover rates of any industry. In some places, turnover exceeds 100%, meaning that some plants replace more than their entire workforce each year.

All of this has created a serious vulnerability to COVID19. Workers packed closely together, working rapidly, disconnected from public services, and feeling pressure to keep working (or coming to work) even if sick, create the conditions for the unchecked spread of the disease. And the centralization of meat—large plants can account for as much as 5% of US pork or beef production—means that just a few disruptions can have far-reaching consequences.

All of this has created a serious vulnerability to COVID19. Workers packed closely together, working rapidly, disconnected from public services, and feeling pressure to keep working (or coming to work) even if sick, create the conditions for the unchecked spread of the disease. And the centralization of meat—large plants can account for as much as 5% of US pork or beef production—means that just a few disruptions can have far-reaching consequences.

Those who want to keep plants running have tried to either blame workers or minimize the problem. One Smithfield Foods employee blamed “certain cultures” among workers, particularly living with extended family for the outbreaks. In Wisconsin, a State Supreme Court justice asserted that coronavirus in parts of the state was affecting meatpacking workers and not “regular folks.” In May 2020, Nebraska health officials stopped reporting coronavirus statistics from meatpacking plants despite climbing case numbers. All of these arguments and measures served to justify keeping plants open despite worker risk.

As meat became essential, its workers became disposable. This was not inevitable. It was a consequence of specific policies and the outcome of many fights, on the factory floor and in courts and legislatures across the country. This was as true in the mid-twentieth century when unions fought for and won a living wage as it is today, when processing work is as exploitative and unremunerative as it was when the industry first took shape.

The collision between meatpacking and coronavirus is a consequence of this story. The history of meatpacking helps to explain why Americans accept an industry that works for consumers, but costs workers and communities so much. If we follow the current trend, meat workers will be sacrificed to please American consumers. But history suggests that this is ultimately a political decision, and perhaps the coronavirus pandemic finally provides us an opportunity to reaffirm what actually is essential and how we value those who provide it.