What does quarantine look like in South Korea? From the inside, it is many layers of paperwork at the airport, an omnipresent Covid-19 tracking app installed on one’s smartphone, and a pristine room in a government facility. It is also a surprisingly sociable experience. This summer in Seoul, being in quarantine hints at what continuing to live with the pandemic may entail rather than a sudden transition into a post-pandemic future.

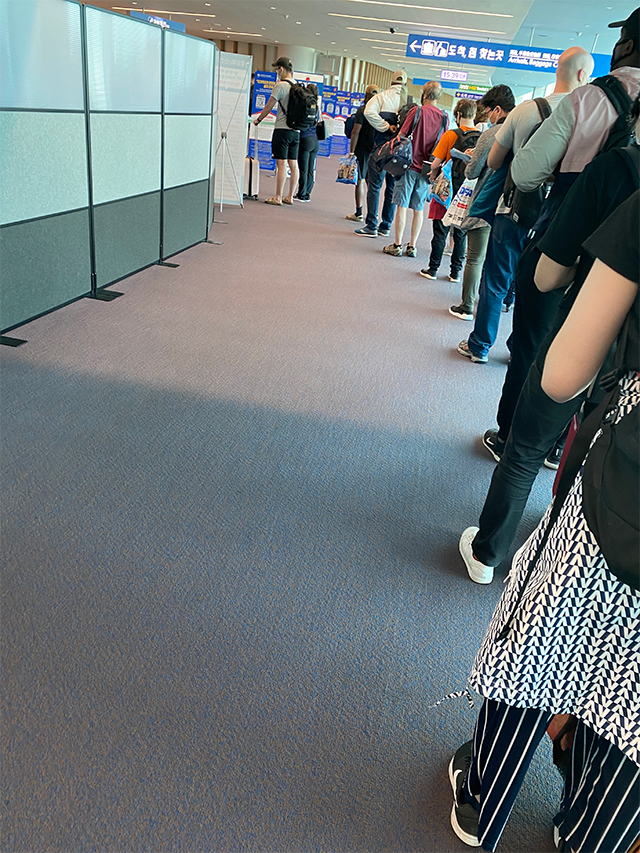

“Please have your papers ready.” The bureaucracy of South Korea’s Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) and Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency is the first to greet new arrivals to the country, who submit a printed copy of a negative PCR test result and two health declaration forms. Evidence of health is scrutinized more rigorously than evidence of legal citizenship or residency status. The MOHW’s airport booth was once the place where people brushed by quickly, hurrying to get to the Immigration authorities before the lines got too long. It is now the opposite. And it feels like the passport serves more as a means for verifying health than for authenticating identity. The MOHW official carefully crosschecks information, circling one’s name, date of birth, type of Covid-test, and the name of the hospital/lab that issued the test. Most importantly, the bureaucrat confirms that less than 72 hours have passed since the PCR test was taken. Time matters. People now have expiration dates that must be administratively checked.

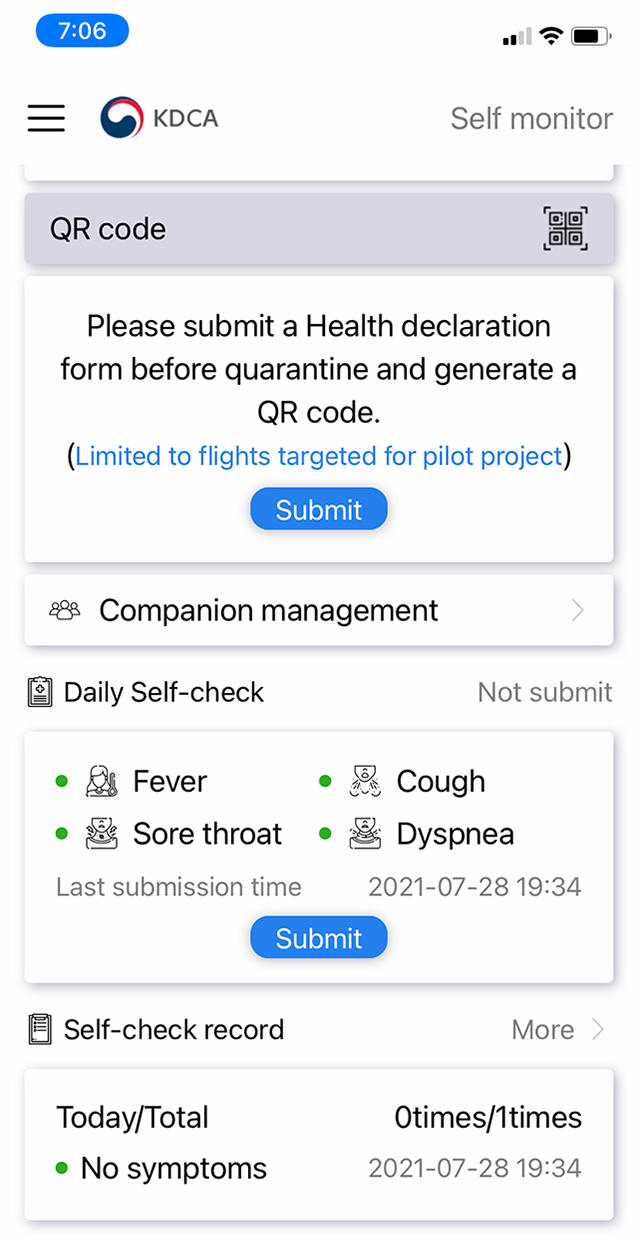

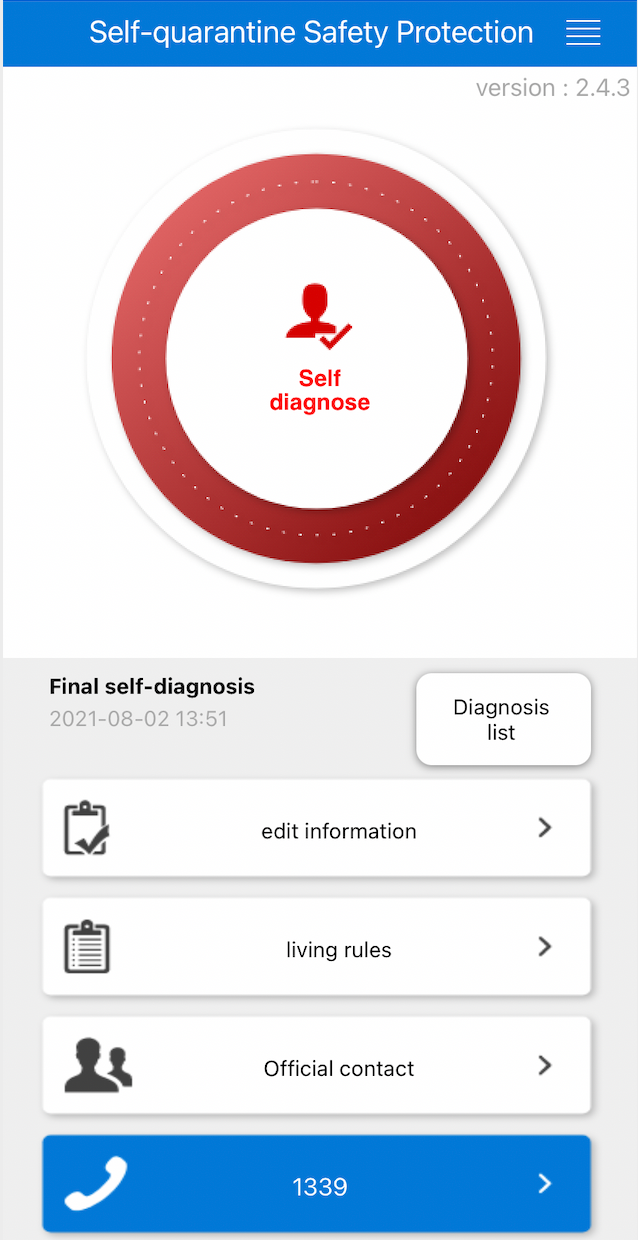

Next, a soldier asks politely: “May I help you install the phone app?” He is no older than 28, likely much younger. He sits next to at least ten other soldiers, hunched over Apple iPhones, Samsung galaxy phones, and other devices. Their thumbs are very busy. It looks as if they are playing videogames on their phones. In fact, they are inputting traveler’s health and contact information into the government’s “Self-diagnosis App” (i.e., Self-Quarantine Safety Protection App). The famed South Korean approach to contact-tracing using apps, which has been both lauded for the efficacy of micro-level monitoring and criticized for data privacy concerns, is in part made possible through the adeptness of young military recruits with mobile operating systems for smartphones. The app’s interface is complicated. While for those in Korea, contact-tracing has become a way of everyday pandemic life, the nut-and-bolts of the process—self-reporting of symptoms, monitoring through GPS-based location data, compliance enforcement—is not necessarily intuitive. “We volunteer to be stationed at the airport,” explains one of the phone-savvy young soldiers. The armed forces of South Korea make quarantine work. It is an extraordinary intervention into the realm of border control, law enforcement, and population management that feels remarkably normal.

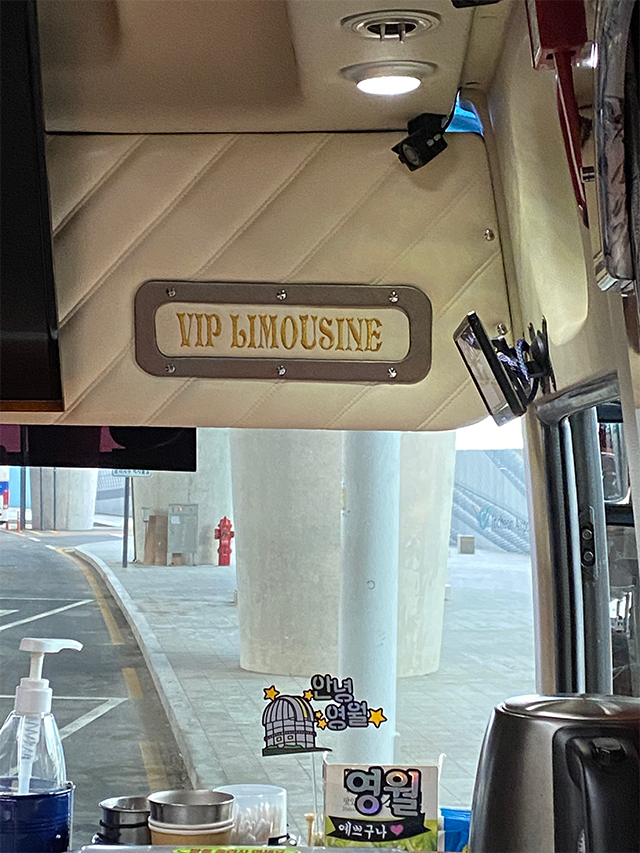

Now, a police officer appears. He dressed in a blue shirt and will spend the next 50 minutes riding in a quarantine bus—marked somewhat absurdly as “VIP limousine” with garish pink curtains completely covering the windows. His role is to usher people into the city—either nearby Incheon or metropolitan Seoul—where they will spend quarantine in a government-designated facility. The word “facility” in Korea (shiseol) has a clinical tone, but in the pandemic travel context, it means a temporary home for foreigners, travelers as well as nationals with ambiguous domicile and citizens who prefer to isolate before rejoining their families at home. High numbers of the Delta-variant (and the Delta Plus variant) worry South Koreans in the midst of a frustratingly slow vaccination roll-out and climate of uncertainty about breakthrough infections and changing knowledge about contagion. There is a bit of a gamble however, as one’s own home cannot be chosen at will. “Quarantine facilities are randomly assigned and cannot be changed for personal reasons” warns the official guidelines issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Random assignment means the discretion of the police, like the blue-shirted officer in the pink curtain bus.

“Which facility are we going to?”

We’ll be going to [NAME] hotel, ma’am.”

“Is it nice?”

“Very nice.”

The very nice facility is located in the heart of one of Seoul’s business districts, north of the Han River. Quarantine is 14 days spent in a box-shaped hotel room of 20 x 5 m2 with three beds squeezed into it (rather than have a single bed with bedsheets changed three times). Meals are delivered three times a day, placed in a white basket outside the door. There is variety, ranging from a picturesque Korean dish of a bibimbap to more mundane boiled eggs and yogurt, pasta and pork cutlets. Trying to predict what meal will come next becomes a mild obsession.

The very nice facility is located in the heart of one of Seoul’s business districts, north of the Han River. Quarantine is 14 days spent in a box-shaped hotel room of 20 x 5 m2 with three beds squeezed into it (rather than have a single bed with bedsheets changed three times). Meals are delivered three times a day, placed in a white basket outside the door. There is variety, ranging from a picturesque Korean dish of a bibimbap to more mundane boiled eggs and yogurt, pasta and pork cutlets. Trying to predict what meal will come next becomes a mild obsession.

Trash is to be placed in a bright orange bag, and taken away every morning. A cheerful voice makes regular announcements—at 8 am, 11:30 am, and 4:30 pm—reminding everyone to retrieve their meals, put out their trash, and that “leaving your room is strictly forbidden.” In Korean, the cheerful voice alternates between referring to “you” as a “customer” (gogaek) and “resident” or “inmate” (ibsoja). It is nothing jarring, and the language use does not sound pejorative. Rather, it underscores the ambiguous status of those inhabiting such facilities during these uncertain times.

A lightbulb goes out. Dial 5 on the room phone and a brisk voice responds “Situation room, how may I help you?” After a bit of confusion, the brisk voice promises to fix the situation. Soon, a person covered from head to toe in a white protective suit, with goggles, is entering the room gingerly. He (or she) tiptoes to the errant lamp, quickly changes the bulb, and exits swiftly. “Thank you!” Back turned, he (or she) waves energetically in response.

The room is bright again. Dusk is falling on a city that is quieter than this space of quarantine. Seoul is in its strictest form of “Level 4” social distancing, which means that gatherings of more than 4 people are banned and after 6 pm, the cap is further limited to 2 people. Here, within the facility—this odd temporary home for people whose distinctions of citizen, national, sojourner, and resident blur under a common quarantine status—it is not pure isolation but another yet form of social distancing that occurs. The orange trash bags are collected. Food is delivered. Covid-19 tests are administered. The muffled sounds of a service economy at work are audible. Doors open simultaneously and people exchange awkward smiles as they retrieve their meals from their white baskets, but no one speaks. It has only been six days, but new habits have already formed, alongside adjusted practices of social interaction.

Diana Kim

August 2021