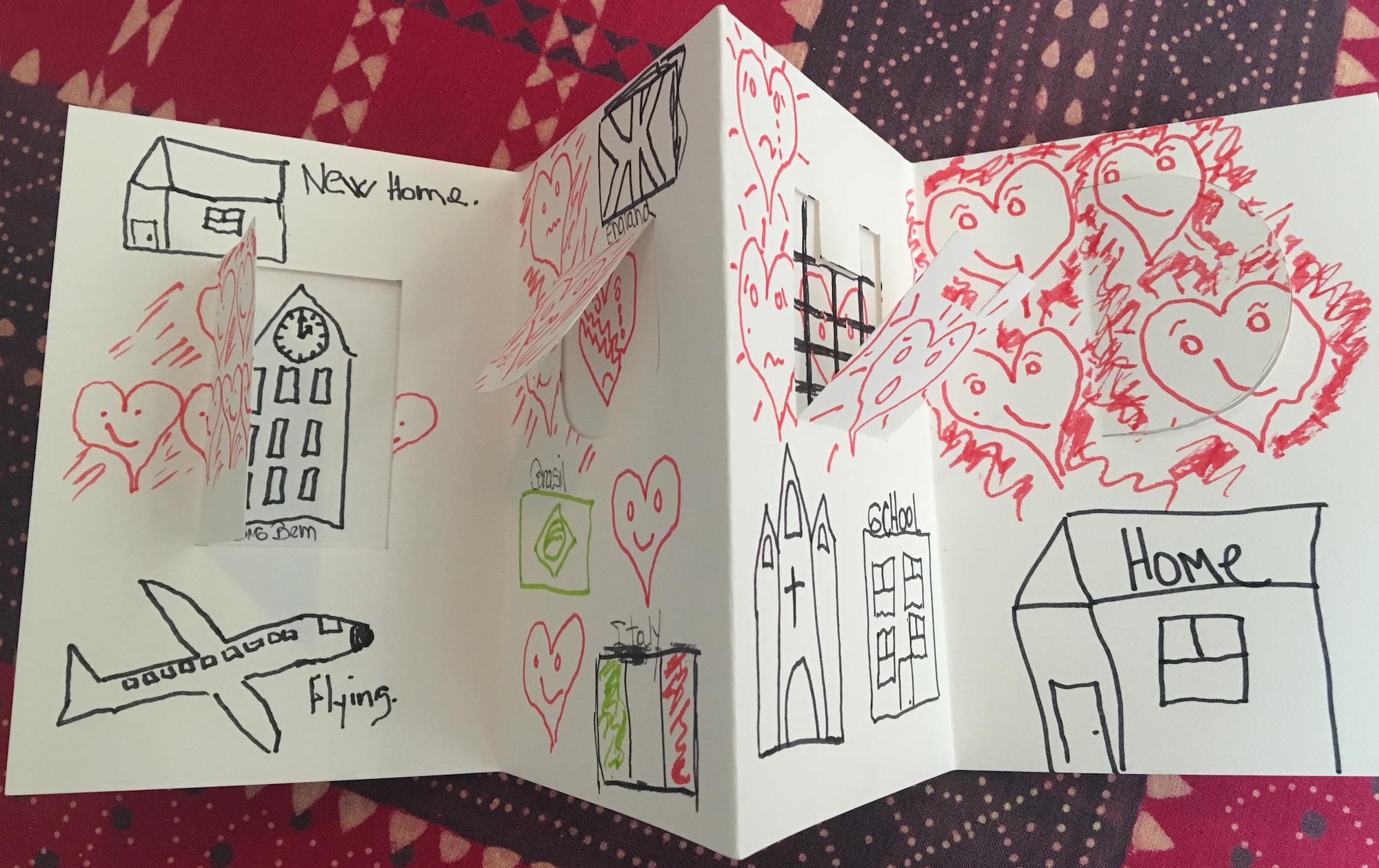

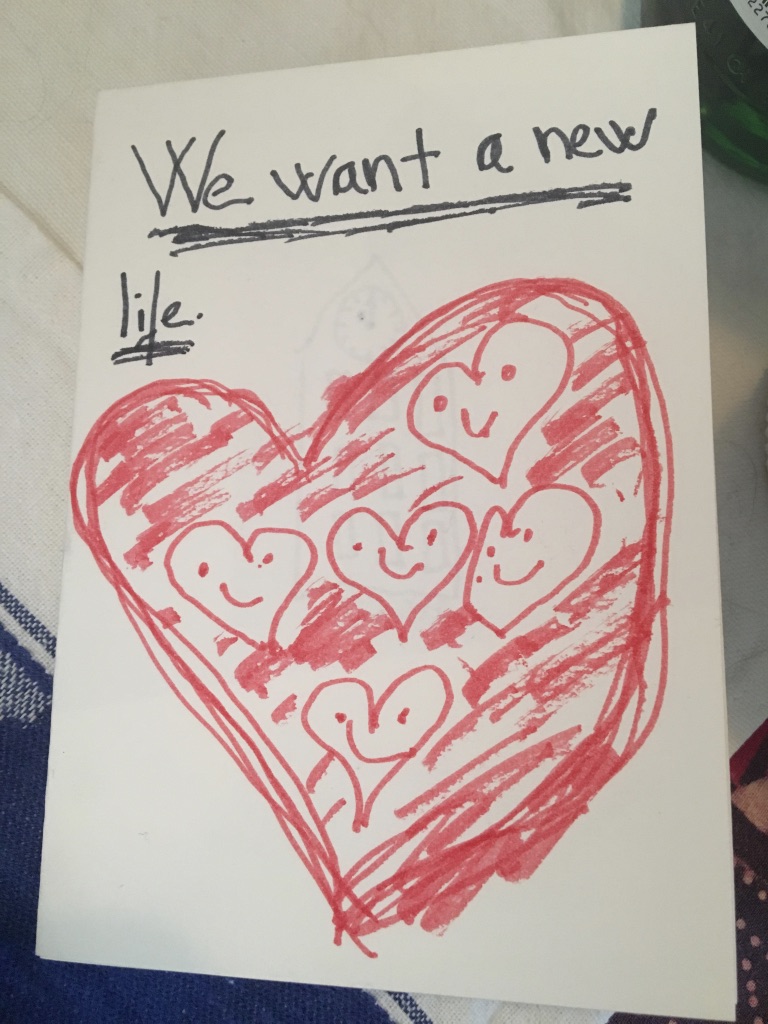

It was mid-March 2020: before. The prison family reading project, Making it Up, was nearing fruition, and prisoner fathers had been working with us for weeks to make storybooks for their children. The family visit event around reading, when the fathers would present their books to their children, was planned in a few days’ time. Outside, the rumour was that a full lockdown was imminent in England, there were already alerts around travel and my colleague was unable to come into prison so I would be taking the monthly reading group. Outside the atmosphere was electric, but inside the prison seemed much as usual. Staff had told me that they were trying to play down the threat of the lockdown out of concern for its psychological effect on the prisoners. As always, we met in the busy library - prison libraries are noisy and active, places for company and conversation. There were nine men in the group and an officer joined us halfway through. Prison Reading Groups (part of Give A Book) are voluntary and informal; they encourage sociability, discussion and connectedness, and run on the principle of choice in a place where choice is hard to come by.

That March the men had chosen to read A Kestrel for a Knave by Barry Hines. The discussion ranged widely, as always. We had a long excursus on racism in England and I promised to bring in Noughts and Crosses by Malorie Blackman (recently televised) next time. We often read a few passages aloud to get us started - this is again entirely voluntary, as members might be emergent or unconfident readers or might have difficulty reading in English. The men help each other if they stumble over a word. That day we read around a bit. Our book triggered powerful memories. Several men spoke about brutal early lives, in and out of prison, in and out of care. - "You think that’s tough,” one man said, and told us a story or two of his own. Inevitably we talked about lockdown. The men had picked up that “on the out”, people were genuinely alarmed at the prospect of being locked down for a few weeks. “So what’s the big fuss about a few weeks locked down - ?” They were sanguine, amused even. People would find out. And life wouldn’t change so much for them.

A couple of days later, along with London - catching up with the rest of the UK, and the rest of Europe - the prison sector locked down. That is to say, all movement around prisons stopped, work stopped, face to face education stopped, as did all voluntary sector activities upon which many prisons rely. Access to the gym, the library and family visits - everything stopped. The Making it Up family reading event was cancelled. We had no idea when the reading group would meet again.

Out in the out, the lucky ones who were well, supported, with space and internet, enjoyed cautious walks in a spring that was the most ravishing ever - “You could hear birdsong!” - discovered Zoom, and Netflix, deliveries by van or kind neighbour, and on Thursday nights joined the world on doorsteps, in windows, and on balconies, to clap for the National Health Service. Anticipating a catastrophe inside - “We imagined the chapel full of body bags - ” an officer told me - prisoners were locked in their cells for 23 ½ hours a day. And thus, were kept remarkably safe. Prisoners were grateful, staff were appreciated, the newly set up “thanks page” of the national prison newspaper was overwhelmed. And had to be cancelled.

Inside prisons, everyone clapped too - on plates and doors and out of barred windows, clapping also for the staff who looked after them.

With libraries closed, library staff unable to go in and crucially no internet in prisons, Give a Book/Prison Reading Groups began sending in boxes of new books where they could be distributed by officers on the wings. We chose books that would appeal to emergent as well as experienced readers. Books and reading really came into their own. Then, in August, the librarian of a large prison got in touch. She was setting up a remote lending service and particularly wanted to reach an isolated group of prisoners who couldn’t access resources with information only available in English: those, in effect, imprisoned again by language. She sent us a friendly and informative notice of the library offer, The library service is committed to providing the best possible service to all prisoners at HMP XXXXX. During the Covid lockdown, the library is not open to visit. Instead, we are delivering library resources to you on the wings. We have books, CDs, DVDs and magazines for you to borrow. There was information on how to access these, and she sent a request for help in translating it into 10 languages.

We put out a call.

We found Albanian through a quadrilingual Greek former EU worker, now based on a Greek island, who knew an Albanian-Greek speaker. Arabic translations came to us from a scholar of 19th century Ottoman Lebanon who did the translation during his child’s nap - the day-care was closed for a Covid case, and his wife, a bankruptcy lawyer, was overwhelmed by the deluge of new work. He had to look up a few things - 21st century media Arabic being quite different from the 19th century Ottoman Arabic that he was used to. The diplomat son of an old friend provided a different Arabic translation. People were unfazed by prison information shorthand, and translated it even if they didn’t know what it meant.

Amartya Sen handwrote the notice in Bengali, finding something more poetic in the word Wing than is usual. His Delhi-based journalist daughter then typed up his version, making it less literary and more colloquial. Former schoolteachers from our team sent in more. A newspaper editor in Delhi gave us the Hindi translation. His daughter [aged 10] chanced upon him translating it and wanted to know “if there are enough books in all these languages that the form is being translated into - because clearly the readers would not be reading English books. I am sure there are enough for now, but if there are ways of sending them across, we could help source books in Indian languages ….. “ A remote dialogue began with the librarian, a bridge through books - : “That is so lovely… We currently have 32 books in Bengali and 13 books in Hindi in the library. More books are always welcome.” The librarian spoke to the prisoners “who would be very happy to have any books but their favourite would be translations of best-selling psychological thrillers and crime dramas by authors such as John Grisham and Lee Child. …Having heard I was asking about foreign language books, another prisoner has requested books in Bosnian, … I'm glad it's opened up this possibility for the Bosnian prisoner too. Starting this debate can only be a good thing and hopefully word will spread, despite language barriers.”

Hungarian came to us through an academic friend of a friend, Polish from an emergency room paediatric neurologist in a major hospital in Baltimore on her evening off. Romanian from an economics professor and an instructor in Romance Languages. Russian from an ex-prisoner author who had donated his work to Prison Reading Groups, and also from a publisher-author who learnt Russian in her 80s and has everything available in Russian literature on her Kindle. Urdu came from a Preceptor in Hindi and Urdu via a history professor. With Vietnamese there was some disagreement over the several different ways to translate the words "prisoner" and “cell” so that they would not sound disrespectful to Vietnamese inmates nor presume guilt. The translators settled on the most polite versions. Lithuanian proved the most difficult - we approached an opera singer, a director and a publisher but it was the time of particularly intense trouble with Belarus so perhaps their minds were elsewhere. But then, through a theatre contact, the UK head of the Lithuanian copyright agency stepped up - and we had all 10 languages.

The remote conversation with the librarian went on: “I wanted to let you know the translations have so far been delivered to 18 grateful prisoners who speak little or no English… And I'm sure benefits will continue as time goes by.” And then: “I wanted to let you know we were moved to receive phone calls in the library on the PALS line from prisoners unable to speak English but we can understand when they say 'Lithuania' or 'Albania' or 'Hindi'. We know their cell number from the phone call and we are delivering books in their language to their cells. Please pass on our heart-felt thanks to all your lovely translators.” *

The response from the translators was heartening indeed - they were enthusiastic, moved to help, and affectingly grateful to play their part in this effort. They were quick to offer more help if needed. Those exquisite and fascinating scripts provided a glimpse into larger worlds of connections, outside the small enclosed world of prison. Maybe it’s because so many of us are away now, cut off from loved ones or home, that this movement to connect people - who are in effect triply isolated - clearly touched the hearts of everyone who helped build these bridges of words, of books. **

Back to March. The group had also been reading Macbeth in a parallel, modernised and original text. At first, one man objected to being cast as second witch but another explained that the witches were part of the plot. So they read the scene aloud in Shakespeare’s language. There was a spontaneous round of applause in the library.

We usually end a group by reading a poem. That day, I’d brought in Emily Dickinson’s ‘Hope’ is the Thing with Feathers. The officer who had joined late asked if she could keep a copy. After a swelling silence the man who had told us about his brutal early life suddenly spoke, That’s what it’s about, this book, it’s about hope.

Victoria Gray

Give a Book

Prison Reading Groups

November 2020

* The Royal Society of Literature has been working with us. RSL Fellows now send us their foreign language editions to distribute to prisons.

** Prisons remain mainly locked down (November 2020). I sent in copies of Nought and Crosses to be distributed by an officer, but don’t know when our group will be able to meet again.