After the February 2021 storm that froze over Texas, it felt like a good time to revisit the themes of Houston, climate change and loss. Yet in the days, then weeks, afterwards, every time I tried to write something, I quickly became stuck.

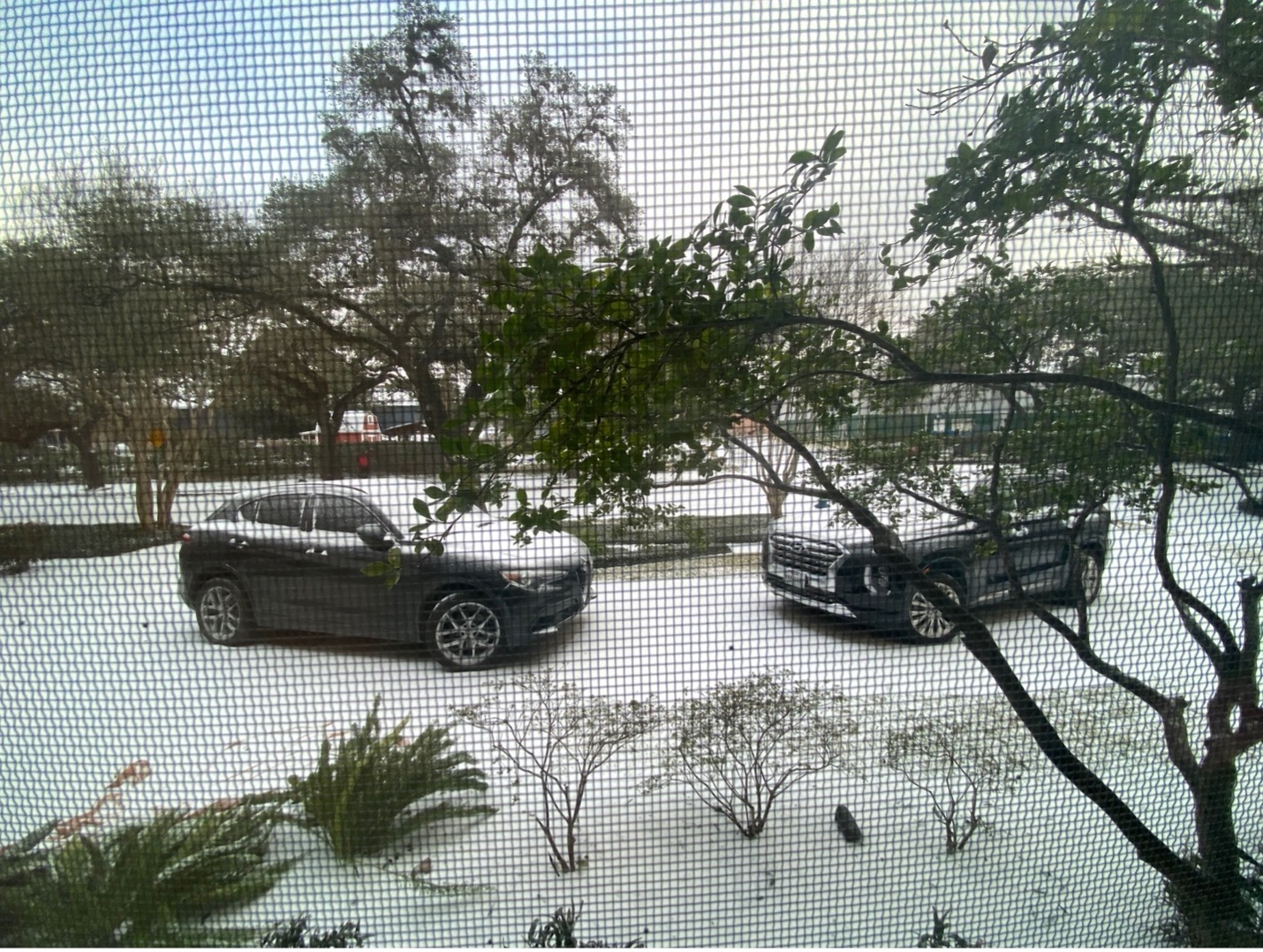

Since last July, I’ve spent the pandemic outside Rome in Italy with my wife’s family. Because of the time change, I only found out about the scope of the storm from photos like this one (taken from my sister’s front window) waiting for me on my phone when I woke up.

I thought, maybe I’ve just been too far away, in all too many respects, to pick up this thread again.

In late March, came the news of the passing of the famous Polish poet Adam Zagajewski. I knew of him, for sure, but I cannot say I knew his poetry all that well. Zagajewski taught at the University of Chicago in the Committee on Social Thought, where I am now a member, but before my time, in the late 2000s. The remembrances that came pouring in from my colleagues were so moving that I could not help but turn to some of his words. Zagajewski’s extraordinary essay “A Defense of Ardor” begins by listing the different steps in a life mostly spent in exile:

“From Lvov to Gliwice, from Gliwice to Krakow, from Krakow to Berlin (for two years); then to Paris, for a long while, and from there to Houston every year for four months; then back to Krakow.”

Before Chicago, Zagajewski taught at the University of Houston. The essay recounts some of his impressions of these different places, before this: “Finally, at this brief list’s conclusion, I came to know Houston, sprawled on a plain, a city without history, a city of evergreen oaks, computers, highways, and crude oil (but also wonderful libraries and a splendid symphony).”

I admit, my heart sank a bit when I read "a city without history." The point I was driving at in my own essays was that Houston does have a history, and it's a fascinating and important one! But quickly it dawned upon me that Zagajewski must have known that. So, what did he (through his translator) mean exactly?

The next essay I read, which included a discussion of precision in poetry, made plain that Zagajewski was careful in his choice of words—not that I would ever doubt that. Dipping ever so slightly into his poetry, immediately it became clear that a number of the reflections by critics published in the days after Zagajewski’s death—that he was a poet of “the night, dreams, history and time, infinity and eternity, silence and death,” who wrote “about the presence of the past in ordinary life: history not as chronicle, but as an immense, sometimes subtle force inhering in what people see and feel every day—and in the ways we see and feel”—were on the mark. Zagajewski even wrote a book of prose titled Two Cities: On Exile, History and the Imagination (1995).

I went back to the phrase, “a city without history,” and I think I might now know what he meant. Zagajewski did not say Houston had no history. He said Houston was a city without history. Houston is a city that, in its culture, or in its architecture and built environment, has little consciousness of itself as a place or a community located in the duration of historical time—beyond quips such as that, due to, say, its racial diversity, it represents “the future.” Or, Houston’s historical consciousness is so highly distorted by its residents’ fantasies of the city, as, for instance, the emblematic “free enterprise city,” that it cannot matter for much.

A city without history. This helps me understand what I was trying to do in my essays, and, I suppose, what I try to do every time I sit down to try and write. History is not given, to be revealed, just because there is some past at hand. To be a subject, with history, is in some important sense to have acquired it, by effort, and therefore to be with it. By extension it is possible to be without it.

Houston has arguably been without history, in large part, because many of the common narratives about the time during which Houston has existed, and particularly flourished—since 1970 or so—do not work for it. They don’t explain it all that well.

And, having no compelling narrative for Houston—circling back to the main argument I have been trying to make —is a symptom of the fact that there is a gaping absence in our historical consciousness of climate change, which I'm convinced needs to be filled if we, as a human community, with a history, want to face up to the challenge that climate change poses in the present.

When Texas froze, and the lights went out and the taps ran dry, quickly many commentators, especially on the left, blamed the state’s electric utility deregulation for the crisis, blithely mixing things together—climate change bad, deregulation bad… miserable cold.

I have no desire to praise public utility deregulation. But, as a number of experts quickly pointed out, a large part of the history of energy deregulation in Texas concerns the successful incentives the state created first during the 1990s to encourage the production of wind power. Texas’s 1999 energy deregulation law, signed by Governor George W. Bush, did this, unlike an otherwise largely similar law passed that same year in California. Only in 2002 did California pass a law sponsoring renewable energy. In 2005, Texas Republicans passed a $7 billion bill further fostering wind energy in the state, the same year President George W. Bush signed the Energy Policy Act, creating an investment credit for renewable energy, including solar power, which has proved consequential, though no salvation.

So, if one wants to relate the recent winter storm to a story about climate change, typical historical narratives of either the market heroism of a rugged independence or the evils of pro-market deregulation do not work all that well. With respect to renewable energy sources, something more complicated was happening in Texas politics during the 1990s than what many people today assume. There was, at minimum, more contingency, and therefore possibility, than what the most extreme apocalyptic or denialist approaches to climate change would suggest.

So, if one wants to relate the recent winter storm to a story about climate change, typical historical narratives of either the market heroism of a rugged independence or the evils of pro-market deregulation do not work all that well. With respect to renewable energy sources, something more complicated was happening in Texas politics during the 1990s than what many people today assume. There was, at minimum, more contingency, and therefore possibility, than what the most extreme apocalyptic or denialist approaches to climate change would suggest.

After the recent snow and ice, many current Texas Republicans blamed “green” energy for the failure of the power grid during the storm (which is crazy), or even the “Green New Deal” (which doesn’t exist) and then tried to use the storm to argue that the state needed to double down on fossil fuel energy production.

In this narrative, climate change does not exist. Its history is that of a liberal myth, if it is not altogether a hoax. To say the least, this is another narrative that does not ring true.

Consider another narrative that circulated after the storm, concerning whether it was “caused” by climate change. It is possible, some scientists think, that the warming of the planet has altered the jet stream so that cold blasts of air are now more likely to find their way further south than in recent memory. But the evidence for this is not definitive.

The debate will go on, as it should, but it is unrelated to another issue I tried to raise. The causes of climate change, important as they undoubtedly are, do not address concretely another urgent matter—living with climate change.

And, stipulating that anthropogenic climate change exists, caused most fundamentally by our fossil fuel energy system, a lot happens in Houston that even if it cannot be directly attributed to climate change by climate scientists—at the scale at which they work—is still about climate change. What is true of all of our cities is especially true of Houston. At the scale of everyday life, down to its most mundane details, one cannot live there—even in the most normal circumstances, let alone when there is an atypical winter storm—without living climate change.

As I write this, public discourse about the winter storm in Texas has already faded. But it proved to me, yet again, that we have a lot of work left to do if we want to be with an adequate history of the climate.

There are plenty of reasons to be optimistic, and I cite all of the wonderful essays that have been written for the Center for History and Economics project on Visualizing Climate and Loss.

But to return to Zagajewski. Somewhere in the same neighborhood of the thought Houston is a “city without history” is the thought that Houston—with all its highways and crude oil—is a city without poetry. But, among other poets of course, Zagajewski wrote many poems in Houston. He even once commented in an interview that Houston had turned out to be “a good place for my writing.”

Here is Zagajewski’s poem, “Houston 6 p.m” from his Mysticism for Beginners (1997), translated by Clare Cavanagh.

Houston, 6 p.m.

Europe already sleeps beneath a coarse plaid of borders

and ancient hatreds: France nestled

up to Germany, Bosnia in Serbia’s arms,

lonely Sicily in azure seas.It’s early evening here, the lamp is lit

and the dark sun swiftly fades.

I’m alone, I read a little, think a little,

listen to a little music.I’m where there’s friendship,

but no friends, where enchantment

grows without magic,

where the dead laugh.I’m alone because Europe is sleeping. My love

sleeps in a tall house on the outskirts of Paris.

in Krakow and Paris my friends

wade in the same river of oblivion.I read and think; in one poem

I found the phrase “There are blows so terrible…

Don’t ask?” I don’t. A helicopter

breaks the evening quiet.Poetry calls us to a higher life,

but what’s low is just as eloquent,

more plangent than Indo-European,

stronger than my books and records.There are not nightingales or blackbirds here

with their sad, sweet cantilenas,

only the mockingbird who imitates

and mimics every living voice.Poetry summons us to life, to courage

in the face of the growing shadow.

Can you gaze calmly at the Earth

like the perfect astronaut?Out of harmless indolence, the Greece of books,

And the Jerusalem of memory there suddenly appears

the island of a poem, unpeopled;

some new Cook will discover it one day.Europe is already sleeping. Night’s animals,

mournful and rapacious,

move in for the kill.

Soon America will be sleeping, too.

I picture Zagajewski, living and writing in Houston during the 1990s. This poem, like so much else happening in Houston at that time, was not exactly about climate change. Nonetheless, somehow it still was.

JonathanLevy

April 2021