Historians looking back on the Coronavirus pandemic will have no shortage of representative images to choose from. The facemask. The Zoom rectangle. Cannibal rats. For me, the enduring image of the pandemic will be a bird. When everything began to shut down in the United States in March 2020, I took up birding. Before I knew it, birding became my pandemic hobby. Pandemic hobbies have become the subject of think pieces and the butt of jokes. A sudden spike in breadmaking caused nationwide yeast shortages. Knitting became more popular. I was hardly alone in my newfound interest in birds. Sales of bird supplies have soared. Birding seemed like a logical choice to me. It was an outdoors activity with a low barrier to entry that kept me active when my routine suddenly became sedentary.

Hobbies can be a welcome respite from the pandemic, but they cannot provide escapes from the realities of power. The day police murdered George Floyd, a white woman in New York called 911 to falsely accuse a Black birder, writer Christian Cooper, of threatening her after he asked her to leash her dog. The incident launched national conversations about “birding while Black.” Birding is inherently political. It raises questions about visibility and access, labor and leisure, belonging and privilege.

I am acutely aware of the role the history of segregation played creating the conditions that gave rise to my own birding. I lived in a part of Madison, Wisconsin where I had grown accustomed to the sight of common birds like robins and cardinals. They frequented my yard, trees, and lawn—all of which I had for the first time. Homes had these features because the neighborhood was developed as a segregated suburb in the 1950s. In my book, How the Suburbs Were Segregated: Developers and the Business of Exclusionary Housing, 1890-1960, I trace how white realtors and policymakers codified planned communities of segregated single-family homes as the most valuable residential real estate in the US. Suburbanites in these bird-friendly neighborhoods continue to drive inequality in Madison as well as in the rest of the country. My gateway to birding was a built environment of ranch houses that epitomized an American dream predicated on exclusion. I have since moved to Florida, where the birds are different, but the history of housing segregation bears marked similarities.

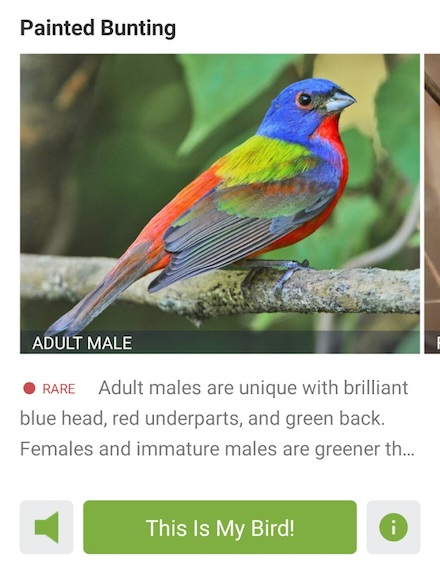

Birding keeps me safely away from people, but it has actually broadened my sense of community through the digital tools Ebird and Merlin. Ebird lets users submit checklists of birds they spot. It georeferences the checklist and has features to upload photographs, video, and audio. The community aspect comes from how everyone’s checklists are publicly available. I can sort through all the sightings in so-called hotspots anywhere in the world, including near me, or see all the lists another user recently uploaded. Merlin is a field guide that will show the most likely birds in one’s area on that day, with information, photos, sounds, and identification tips. Both digital tools make birding feel like a game: If I spot a bird for the first time, I can try to confirm the species by checking Merlin. Once sure of the species, Merlin provides the irresistible “This Is My Bird!” button to tap.

Birding keeps me safely away from people, but it has actually broadened my sense of community through the digital tools Ebird and Merlin. Ebird lets users submit checklists of birds they spot. It georeferences the checklist and has features to upload photographs, video, and audio. The community aspect comes from how everyone’s checklists are publicly available. I can sort through all the sightings in so-called hotspots anywhere in the world, including near me, or see all the lists another user recently uploaded. Merlin is a field guide that will show the most likely birds in one’s area on that day, with information, photos, sounds, and identification tips. Both digital tools make birding feel like a game: If I spot a bird for the first time, I can try to confirm the species by checking Merlin. Once sure of the species, Merlin provides the irresistible “This Is My Bird!” button to tap.

After I submit a checklist to Ebird containing the species, a little checkmark will appear next to the entry in Merlin. Then I can share with other birders that I got a “lifer,” meaning I saw a species for the first time. Ebird lets me or other users view my lifer list of what I have seen, where, and when. I will sometimes drop what I am doing if someone reports a possible lifer nearby. The brilliance of Ebird and Merlin, however, is that they are actually citizen-science projects. Created by Cornell Lab of Ornithology, they provide one of the most comprehensive sets of data available to understand a huge array of environmental phenomena.

Learning about the lives of birds through these tools has therefore also been a lesson in interconnectedness. An environmental change can ripple out to affect birds thousands of miles away. Ebird data has helped make impact legible. Take last year’s irruption of pine siskins who left their range in Canada due to food shortages and spread out all over the United States and Mexico. The timing and extent of the irruption is known due to the thousands of user submissions of pine siskin sightings where they would not ordinarily occur. There is also the process of short-stopping in which average temperature increases have caused migratory birds to shorten their typical migration to locate suitable nesting sites close by, saving energy. And as 2020 was a year of unprecedented weather and fire events, I cannot help thinking about the plain-looking veery I recently spotted in my yard, that I had never heard of before consulting Merlin. A recent study using Ebird data concluded that veeries can predict the severity of hurricane season in the Southeast United States based on signals they pick up while in South America.

Because birding has attuned me to this interconnectedness, the lifer I have been most exited by is the endangered snail kite, whose range in the United States is limited to parts of Florida. It was one of the first species federally classified as endangered following the 1966 passage of the Endangered Species Preservation Act. The timing of the act was no coincidence as the same massive post-war boom that gave rise to many segregated suburbs devastated ecosystems throughout the country. The snail kite is a marvel of adaptation. Everything about its beak shape, senses, and flight make it the perfect hunter of the only thing it eats: the apple snail. This specialization, however, has made it vulnerable due to rampant development, which resulted in both loss of habitat and degradation of the snail’s water sources. Now the snail kite faces another threat: climate change. Rising sea levels from an average temperature change of 1.5 degrees Celsius would result in massive habitat loss of its already limited range, while the increased possibilities of heat waves and heavy rain would hinder nesting and feeding young. 1.5 degrees is the target established by the 2015 Paris Agreement. The US withdrew from the agreement in 2020. Even though the Biden administration plans to rejoin, the target might still be a best-case scenario for the snail kite unless it is quickly exceeded.

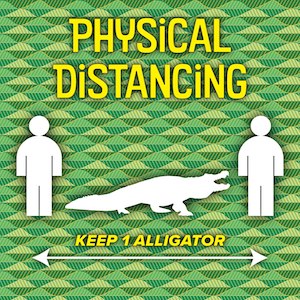

I did not count on seeing a snail kite when I did. Armed with my binoculars and my phone opened to Ebird, I put on some hiking boots and trekked into the prairie south of Gainesville, Florida. Even in such solitary places I am reminded of the pandemic that brought me there. At the entrance to the trail, the new signs warning visitors to stay six feet away from people had been erected next to the old ones found everywhere in Florida to keep twenty feet away from alligators. Indeed, other signs around town even play on the distressingly similar risk of death by proximity.

I did not count on seeing a snail kite when I did. Armed with my binoculars and my phone opened to Ebird, I put on some hiking boots and trekked into the prairie south of Gainesville, Florida. Even in such solitary places I am reminded of the pandemic that brought me there. At the entrance to the trail, the new signs warning visitors to stay six feet away from people had been erected next to the old ones found everywhere in Florida to keep twenty feet away from alligators. Indeed, other signs around town even play on the distressingly similar risk of death by proximity.

Before long a dark raptor swooped down over the water, gracefully skimmed the surface and flew off with something I could not identify. Only when I got home and ran a photograph through Merlin did I learn I had seen a snail kite hunting an apple snail. I read about the snail kite because of my new-found love of birding and took heart in how my pandemic hobby could play a role in its survival.

My Ebird sighting has become a data point, along with those of the other citizen-scientist birders who share in the excitement of each other’s findings. Now with over six hundred thousand users, Ebird had helped worldwide conservation efforts, from spurring legislative action to expand wetlands protections to shaping environmental planning for the locations of wind farms and communications towers. This is good not only for birds but promising for the future of large issues that affect humans such as climate change or sustainability. With a 44% increase in October sightings on Ebird from the same month in 2019, I am optimistic about the long-term positive impact of all the information submitted by people who spent the pandemic birding. Twenty-six countries saw at least a doubling in Ebird usage in 2020. These include increases of 174% in Angola, 356% in Nicaragua, 243% in Vanuatu, and 348% in Ukraine. Figures such as these suggest that new digital platforms have the potential to thrive even where there are serious obstacles to internet access. Perhaps this enlarged virtual community will foster shared connections worldwide. It is my hope that it will become the basis for new forms of political organizing in the name of environmental conservation, sustainable infrastructure, and an end to the digital divide. Like the veeries picking up early signals of hurricanes, pandemic birding constitutes an early sign of global change.

What other ripple effects will the increased popularity in birding bring? For me, becoming a birder changed how I experience the world. If birding proved a logical choice in March, it was also an unexpected one. I grew up in Brooklyn and only was conscious of pigeons and seagulls until adulthood. It makes me wonder how differently I would experience New York City now. Birds were there all along. I actually grew up within walking distance of the Gateway National Recreation Area, a major stop on the Atlantic Flyway. I always saw the signs but I never saw the birds. Now I notice birds everywhere.

Paige Glotzer

February 2021