City

The history of coal in London often begins with smoke. The most visible and pervasive consequence of coal use, the city was permeated with the sulfur and particulate matter released from its thousands of fires. In time, the metropolis became synonymous with its atmospheric anomaly. Many authors of the period grappled with London’s smoke, and subsequent scholars have followed them, interpreting the emergence of urban pollution as a hallmark of London’s early modernity.

The history of coal in London often begins with smoke. The most visible and pervasive consequence of coal use, the city was permeated with the sulfur and particulate matter released from its thousands of fires. In time, the metropolis became synonymous with its atmospheric anomaly. Many authors of the period grappled with London’s smoke, and subsequent scholars have followed them, interpreting the emergence of urban pollution as a hallmark of London’s early modernity.

As a physical event, the smoke of London was a consequence of two peculiarities: the physical topography of London and the composition of bituminous coal. London sits in the Thames river valley, which provides the setting for “temperature inversion,” during which cold air becomes trapped beneath warm air, creating a lingering fog. The high sulfur content of bituminous coal, commonly used in the coal-fires of the metropolis, combined with this atmospheric moisture to create sulfur dioxide, which is an acid that corrodes materials of all kinds.

The late seventeenth-century writers John Evelyn and Timothy Nourse both identified the problem of sulfur dioxide (in qualitative, rather than chemical, terms) when they described how London’s coal smoke insinuated itself into the materials of the metropolis, dissolving building surfaces and connective tissues. Evelyn, a well-known natural philosopher and founding member of the Royal Society, speculated in his 1661 essay Fumifugium that the city’s smoke caused the buildings and furniture of the city to deteriorate more in one year than “expos’d to the pure Aer of the Country it could effect in some hundreds.” The lesser-known agricultural writer Timothy Nourse, in his “Essay upon the Fuel of London,” repeated this claim and added detail. He described how iron in London became “in a few Years … Eaten and Mouldring with Rust” and how stone was “eaten away … to the very bone.” “[S]o piercing is this smoak,” he continued, “that it works itself betwixt the joints of Bricks, and eats out the Mortar; so that what was Fresh and Beautiful Twenty or Thirty years ago, now looks Black, Old and Decay’d.”

In their respective essays, both Evelyn and Nourse offered schemes to repair the city’s pollution. Evelyn’s famous scheme identified the industries he thought were responsible for the smoky air—brewers, soap-boilers, lime-burners, and others— and proposed displacing them “five or six miles distant from London,” into and beyond the poorer eastern end of the metropolis.

By contrast, Nourse outlined a material solution, a scheme to restore wood as the primary source of London’s fuel. If Evelyn’s plan is well-known as a formative example of environmental and urban planning, it is Nourse’s scheme that shows more clearly how the fossil-fueled city presented new problems, ones which were less about the appearance of space than about the composition of a material metabolism that had physical, spatial, and temporal consequences. It was only by attending to the fuel directly, Nourse suggested, that the coal-fired city could be reckoned with.

Nourse’s “Essay on the Fuel of London” proposed planting an immense, managed forest that would surround the metropolis, a renewable supply that would reinstate the slower fuel of wood. In his essay, he worked through the material requirements of his plan. What “Quantity of Wood,” he asked, “may probably be sufficient, to serve the occasions of so vast a City?” And how “vast” was London, in reality? How much coal did the city actually burn? As historians Paul Warde and William Cavert have recently pointed out, these questions placed Nourse’s text within the history of “political arithmetic,” men like John Graunt and Gregory King who first ventured to capture London and England in statistical form around this same time.

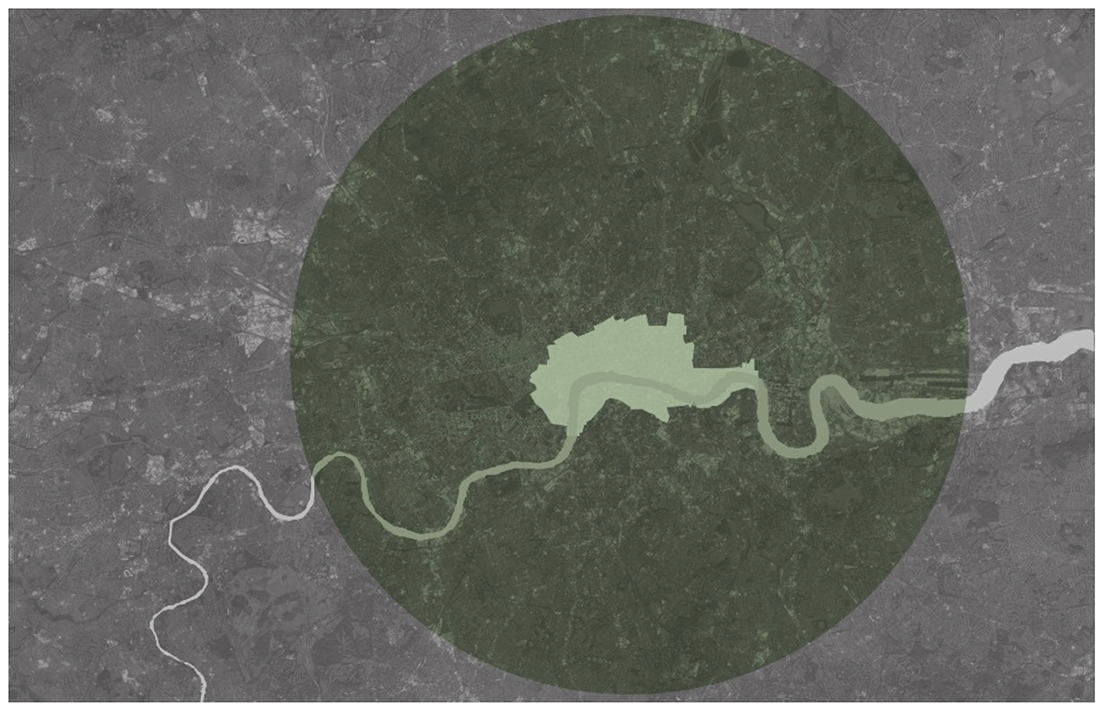

But compared to those other calculators, Nourse was fairly unsophisticated, employing only rough sketches. He worked backwards from an estimated population, a number of chimneys, and an assumed woodland yield, concluding that “Sixty Thousand Acres of Land well planted with Wood” would be able to supply the city. My own rough estimate, based on a period map from 1682, indicates that the built-up area of London at this moment occupied perhaps 2,000 square acres. Nourse, in other words, was proposing an area thirty times larger than the city itself, to supply its fuel, an extent of space—as this diagram shows—that would take up most of modern-day London.

“An Essay upon the Fuel of London” expressed a kind of willful environmental nostalgia. Nourse’s proposal appeared at the end of a long treatise on agricultural improvement, and throughout his book he displayed an understanding of agriculture as a complex of natural and social relations that changed over time. It was perhaps this privileged view as the designer of the rural estate that allowed him to imagine his conservative wooden utopia.

In more immediate terms, however, what is so striking about Nourse’s “Project of Wood-fires” was the closeness of its backward vision. In the 1690s, every other city in the world aside from London was powered by wood or some other organic source of power. Nourse’s counterpoint of wood and coal revealed that the issue was not spatial—as in Evelyn’s proposed industrial displacement—as much as it was temporal, a way of managing change over time. It was as if Nourse immediately sensed the destabilizing effects that coal would continue to bring.

While the visibly polluted air of London has been the subject of much historical interest, the rapid material disintegration that Nourse described in vivid detail was more difficult to capture. The smoke of London merely troubled the eyes and lungs, but the accelerated decay that worried Nourse disrupted the reliability of time itself. It troubled the idea that tomorrow would, in some sense, look like yesterday.

| « Hearth | Boundary » |