Sinking States

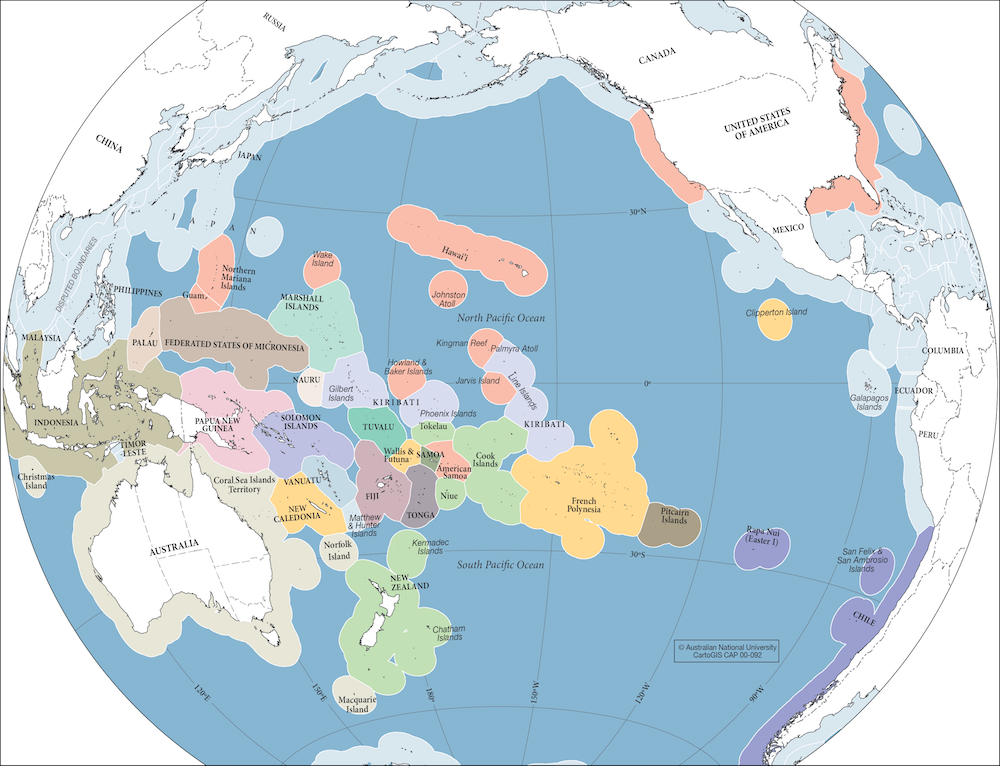

If mass displacement due to rising sea levels is the threat hanging over Asia’s millions, another kind of loss may be in store for their oceanic neighbours. Several Pacific Island states, among them Tuvalu, the Marshall Islands, Kiribati, and the Solomon Islands, face the prospect of a total extinction of their land areas. So do the Maldives and Seychelles in the Indian Ocean. Their low elevations make these states particularly vulnerable; several have already seen a significant percentage of their land disappear under water.

In legal terms, this possibility of total loss of territory raises further questions, beyond the important ones of resettling the populations of these states. These have to do with whether these populations will become stateless peoples. International law indicates certain criteria which much be fulfilled for a state to come into existence; inter alia there must be, to use Judge James Crawford’s phrase, ‘a territorial community under government’. What then to make of islands which will no longer be able to support a territorial community?

Even as they prepare for the practical exigencies of dislocation, these threatened island states are understandably concerned to maintain their independent sovereign status. Some have explored the option of acquiring new land: in 2014, in a desperate measure after a World Bank led adaptation programme was perceived to achieve only doubtful success, Kiribati paid out a sum of $8.77 million to the Church of England to purchase 20 square kilometres of land on a Fijian island. According to former President Anote Tong of Kiribati, who oversaw the transaction, this area may become the new home of his state’s 110,000 people. Yet, while such purchases may confer ownership of property, they cannot confer sovereignty – that must be agreed with the ceding state. Such agreements are difficult to secure. Jane McAdam relates the previous experience of Nauru, which, having suffered massive environmental damage due to irresponsible phosphate mining under the trusteeship of Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom (later the subject of a proceeding brought by Nauru before the International Court of Justice) had sought resettlement on a new island. Australia, willing to offer Curtis Island for the purpose, categorically refused to transfer sovereignty over it to Nauru.

Even as they prepare for the practical exigencies of dislocation, these threatened island states are understandably concerned to maintain their independent sovereign status. Some have explored the option of acquiring new land: in 2014, in a desperate measure after a World Bank led adaptation programme was perceived to achieve only doubtful success, Kiribati paid out a sum of $8.77 million to the Church of England to purchase 20 square kilometres of land on a Fijian island. According to former President Anote Tong of Kiribati, who oversaw the transaction, this area may become the new home of his state’s 110,000 people. Yet, while such purchases may confer ownership of property, they cannot confer sovereignty – that must be agreed with the ceding state. Such agreements are difficult to secure. Jane McAdam relates the previous experience of Nauru, which, having suffered massive environmental damage due to irresponsible phosphate mining under the trusteeship of Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom (later the subject of a proceeding brought by Nauru before the International Court of Justice) had sought resettlement on a new island. Australia, willing to offer Curtis Island for the purpose, categorically refused to transfer sovereignty over it to Nauru.

International lawyers have responded to this unfair eventuality with the suggestion of ‘freezing’ the baselines from which the maritime claims of such states are measured; so that later decreases of land will have no effect on their resource entitlements. Implied here is the adoption of a collective legal fiction, an unconsciousness mental stretching of the area of each sinking state to maintain an agreed upon square mileage. Part of the elegance of this proposal is its reversal of decades of cartographic practice, which has facilitated our common mental diminution of their significance.

| « Fragile Ports | Expanding Shelves » |