The Out-of-Sight Arteries of Globalization

In The Undersea Network, Nicole Starosielski offers the following corrections to our intuitive understandings of the global communications network:

‘It is wired rather than wireless; semicentralized rather than distributed; territorially entrenched rather than deterritorialized; precarious rather than resilient; and rural and aquatic rather than urban.’

99 percent of it relies on a technology that remains out of sight, the undersea cable. A very few links – forty-five from the continental United States, less than five from many other countries – extending outwards (and downwards) from each state support the bulk of world’s phone-calls, emails, videos and other digital exchanges. Connected in a hub-and-spoke fashion, with many newer fibre-optic systems mapping onto older telegraph and telephone routes, the submarine cable network has joined lands across the ocean for over a century.

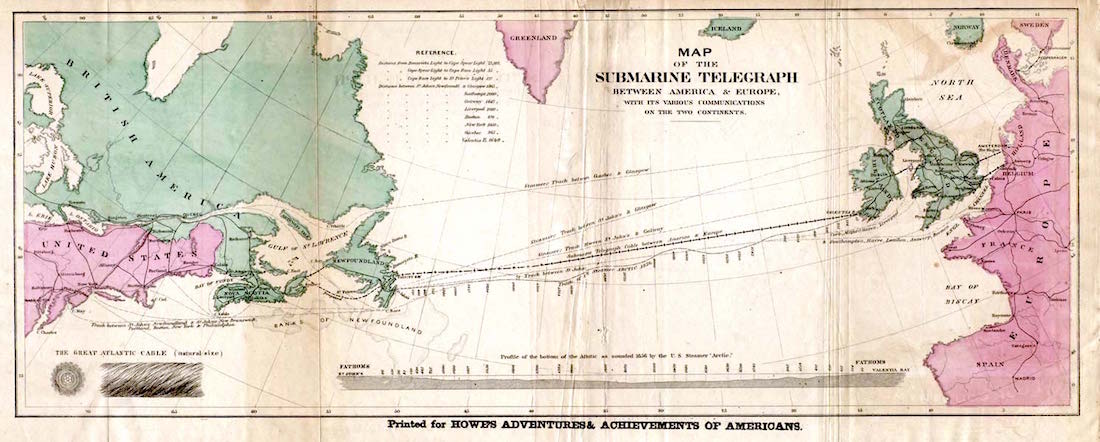

The first transoceanic cable was laid in the mid-19th century, joining North America to Europe via Valentia Island in western Ireland, and Heart’s Content in eastern Newfoundland, Canada. It was laid by the newly formed Atlantic Telegraph Company, promoted by Cyrus West Field; commenced operations on 16 August 1858 with an exchange of greetings between Queen Victoria and US President James Buchanan; and broke down three weeks later. Following the American Civil War, the company – now reconstituted as the Anglo-American Telegraph Company, following several mergers – tried again, and in 1866 succeeded in establishing a more durable connection. Since then, more than 550000 miles of submarine cables have come to connect all the regions of the world.

Yet their ubiquity passes unrecognized, hidden as much by seawater as by ‘a historiographic practice that tends to narrate a transcendence of geographic specificity, a movement from fixity to fluidity, and ultimately a transition from wires to wireless structures’. Apart from distorting our understanding of the mechanisms that underpin global economic exchange, such a historiography occludes the social and environmental toll of submarine cables, as also the regulatory gaps that leave them vulnerable to damage.

In South East Asia, the impact of cables had preceded their presence; their distant use locally producing ‘a Victorian ecological disaster’. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, cable wires used to be wrapped in a naturally occurring latex called gutta percha to insulate them from seawater. This grew in the rainforests of (what were then) British Malaya and Sarawak, the Dutch East Indies, and French Indochina. By John Tully’s calculations, around 800,000 trees were felled to supply insulation for 1858 transatlantic cable. By the early 20th century, submarine cables had accounted for the destruction of 88 million trees.

In South East Asia, the impact of cables had preceded their presence; their distant use locally producing ‘a Victorian ecological disaster’. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, cable wires used to be wrapped in a naturally occurring latex called gutta percha to insulate them from seawater. This grew in the rainforests of (what were then) British Malaya and Sarawak, the Dutch East Indies, and French Indochina. By John Tully’s calculations, around 800,000 trees were felled to supply insulation for 1858 transatlantic cable. By the early 20th century, submarine cables had accounted for the destruction of 88 million trees.

Present-day cables rely on another Asian resource: rare earth minerals. China provides 95 percent of the world’s supply of these minerals, which are also used in the manufacture of smartphones, computers and aircraft. In 2015, a BBC story describing the environmental effects in Baotou, Inner Mongolia, said it felt ‘like hell on Earth’.

If distant environmental effects are part of the political ecology of submarine cables, so too are the – intensifying – uses of the oceans that pose direct threats to them. Cables are at risk of accidental damage from shipping, fishing, oil and gas extraction, and deep sea mining; as well as, crucially, damage that may be intentionally caused as an act of terror or war. They are at risk, furthermore, from the effects of climate change, such as alterations in temperature and currents, and extreme weather events. They may be put to covert uses such as espionage, or be tapped or hacked themselves. International law offers insufficient protections against all these threats. Cables lie at the fuzzy legal intersection of private (usually shared) ownership and (global) public interest, and the law – emphasizing the freedom to lay them – offers limited guidance on the rights and responsibilities that follow.

A current venture spearheaded by three international organizations might provide the catalyst for more comprehensive legal regulation. The International Telecommunications Union, UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, and the World Meteorological Organization are exploring the possibility of using the vast cable network for ocean climate monitoring and disaster warning. Scientists already use cables in marine research, but the telecommunications cable network could produce data at a much greater scale; thereby perhaps also compensating for their ecological costs. The venture has proceeded slowly since first mooted, as many legal and practical hurdles arise. But this is itself a benefit, for we begin to confront issues long kept out of sight.

| « Waterworlds |