Capitalist externalities

The awesome charge -- that Smith, or capitalistic Smithianismus, is the cause of climate change -- is both historical and philosophical. In a historical, or at least a chronological sense, it is self-evidently true that human-created climate change is the outcome of a period in which capitalism has been by far the most important way of organizing economic life.

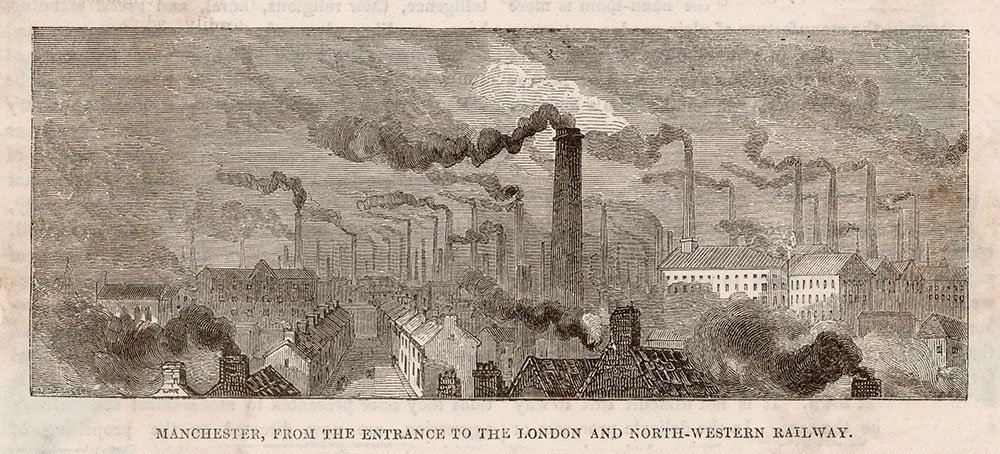

The two centuries of expansion in the use of fossil fuels, from the early 19th century to the present -- consumption of oil, gas and coal

increased to its highest level in history

https://www.iea.org/news/the-world-s-coal-consumption-is-set-to-reach-a-new-high-in-2022-as-the-energy-crisis-shakes-markets.

Oil and gas consumption also increased in 2022, as the world economy expanded.in 2022 -- correspond to a heroic epoch of capitalist production. If capitalism is defined, following the economic historian

Jurgen Kocka,

Jürgen Kocka, Capitalism: A Short History (Princeton, NJ, 2016), p. 21.as a condition of decentralization, commodification, and accumulation, then there are evident connections between the history of capitalism and resource-intensive growth. It was the expansion of property and other rights, in Kocka's account, that made possible the decentralization of economic decisions; markets became the main mechanisms of economic coordination; to own capital was to use resources in anticipation of future gain.

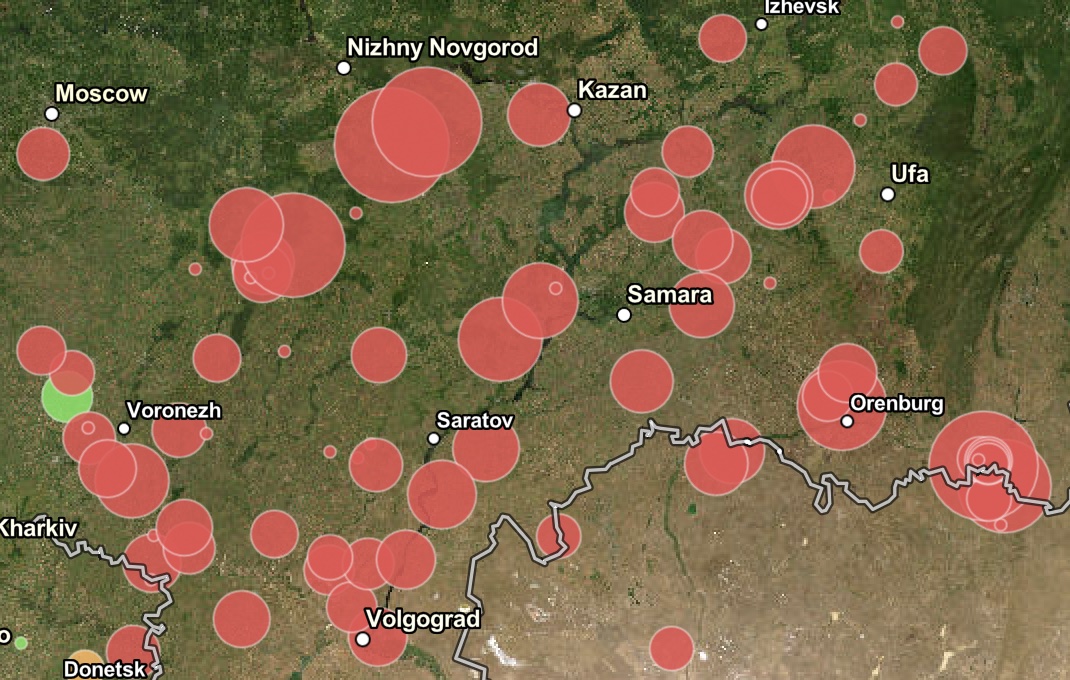

It is certainly the case that a large part of the expansion in energy use since the mid-20th century has taken place in non-capitalist countries. Of the largest methane ultra-emitter sites identified in the 1,800 Histories of Methane project, no fewer than 650 are in the territory of the former Soviet Union, and a further 118 in China; more than forty percent of the total. But over the longer history of resource use, capitalist production has been strongly associated with pollution, including the air pollution of which greenhouse gas emissions are a component.

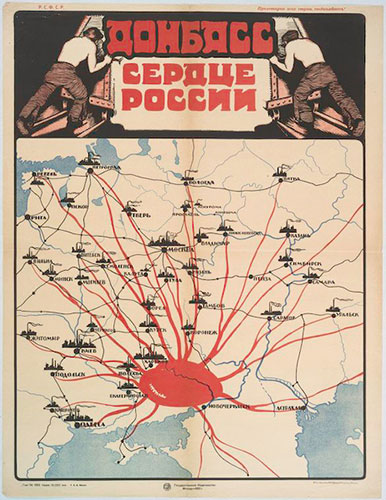

This octopus, or this beating heart of capitalism -- the economy of coal, oil and gas -- has had almost no resemblance, all the same, to Condorcet's idyll of competition and deregulation. It has been shaped, since the age of Smithian growth, by the same political economy of "merchants and manufacturers" that was Smith's own obsession: the coal proprietors who sought "bounties" and extort regulations for their "private interest;" the oil companies, eventually, who by their "impertinent jealousy" excited international conflict, and by their "clamour and sophistry" persuaded everyone else that "the private interest of a part... of the society, is the general interest of the whole."

The political economy of fossil fuel use extended far beyond the interest of the owners of resources in their own markets (as in Fife

Sinclair, "Markinch," p. 548.in 1793, where "the proprietors of coal [had] an interest in great and immediate consumption.") There was an infrastructure of energy consumption -- of waggon ways and railways, pipelines and highways -- that required "public-private partnerships" of the most baroque dimensions, even in peacetime. Some of these were unimagined in Smith's lifetime; others were anticipated in the 18th-century conversations about roads that are so inauspicious, as will be seen, in relation to the contemporary "green economy."

The nation state, in the Wealth of Nations, was a substantially military enterprise, and the "naval stores" of Smith's accounts of regulation -- as in his lists of tar, pitch or turpentine -- were subsumed, during the Napoleonic wars, into a much larger military-industrial-coal economy. This was a capitalist economy, but not a free market economy, as it remains in the Smith tricentenary year; in 2022, "global https://www.iea.org/reports/fossil-fuels-consumption-subsidies-2022fossil fuel consumption subsidies doubled from the previous year to an all-time high of USD 1 trillion." For the economist Paul Sweezy, it was the early history of the British coal industry -- the subject of his PhD thesis -- that provided the most vivid counter-example Paul M.Sweezy, Monopoly and Competition in the English Coal Trade 1550-1850 (Cambridge, MA, 1938), p. 146, n. 16, and see Austin Robinson, "Monopoly and Competition in the English Coal Trade." The Economic Journal, Volume 51, Issue 201 (1941), pp. 101-105.to any assumption that "state action is in some way an 'outside' force as far as the capitalist economy is concerned and hence that the 'pure logic ' of capitalism can be studied in abstraction from political forces."

The philosophical sense of the awesome charge is more obscure. The hypothesis, in general, is that Adam Smith is the theorist, or even the inspiration, of the "atomism" and "materialism" of capitalism. There was an epidemic of self-interest in the early 19th century, in this view, and a collective turning away from social towards individual goods. Individuals as well as enterprises sought to impose costs -- "external costs," in contemporary terms -- on other people and to internalise their own benefits, or profits. Smith was identified, in turn, with a "rationalism" of the enlightenment in which the natural environment was something to be conquered, and not revered. This was even an affinity across the North Sea and the Baltic (as in the exchanges of crooked timber); for the historical economist Bruno Hildebrand, Bruno Hildebrand, Die Nationalökonomie der Gegenwart und Zukunft (Frankfurt, 1848) p. 285, and see Emma Rothschild, "Bruno Hildebrands Kritik an Adam Smith," in Bruno Hildebrand's "Die Nationalökonomie der Gegenwart und Zukunft": Vademecum zu einem Klassiker der Stufenlehren, ed. Bertram Schefold (Düsseldorf, 1998), 133-172. in 1848, Smith "represents the Enlightenment literature of the previous century and can be considered as an economic Kant."

The critique of Smith, here, is an echo of much earlier lamentations. The Wealth of Nations was "the bible of this material and materialist doctrine," the French conservative Louis de Bonald Louis de Bonald, Législation primitive (Paris, 1802), vol. 2, pp. 89-90.wrote in 1802 of the governments of the new century, concerned only with the "administration of things;" for the poet Robert Southey, in 1812, "Adam Smith's book is the code, or confession of faith" of the "moral revolution" of manufacturing. Robert Southey, "On the state of the Poor" (1812), in Southey, Essays, Moral and Political (London, 1832), pp. 111-112.Hildebrand identified Smith with atomism, materialism, rationalism and cosmopolitanism, as well as with the heartlessness of modern times; in Marburg, Hildebrand, Die Nationalökonomie der Gegenwart und Zukunft, p. 183as in Smith's own evocation of the inequality of heat and cold, "in the winter of 1846-1847, at a time of high unemployment, babies were born outside in 10 degrees of cold."

These were assertions about a condition of Smithianismus, more than about Smith himself, and they correspond to very little in Smith's own writings. Smith believed that all individuals, in all times and places, were sometimes, but not always, influenced by self-interest, and that their self-interest was fulfilled sometimes, but not always, by money and goods. Commodities were means to other ends, and in particular to the end of being well regarded. "To be observed, to be attended to, to be taken notice of with sympathy, complacency, and approbation" – these were the advantages to be derived from "all the toil and bustle of this world." Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, p. 50.

The outcomes of self-interested actions were sometimes beneficial in relation to social objectives -- as in the episode of the anxious merchant selling fruit in Konigsberg, in the invisible hand story -- and sometimes not. The central drama of the Wealth of Nations is the effort of merchants and manufacturers to pursue their own interests by political as distinct from economic means, or through political influence and regulation. (Even the social objective in the Konigsberg story -- to increase employment at home without restricting imports -- was constrained by the condition that there were "equal or nearly equal profits" Smith, The Wealth of Nations, p. 454. to be had in domestic and distant uses of capital.)

The gratification of self-interest could also, in Smith's description, have much direr objects than being approved of, or indeed than the accumulation of money and commodities. The "masters of coal works," Smith said in his Lectures on Jurisprudence in 1763, "will never agree" to emancipate their colliers:Smith, Lectures on Jurisprudence, p. 192.

the love of domination and authority over others, which I am afraid is natural to mankind, a certain desire of having others below one, and the pleasure it gives one to have some persons whom he can order to do his work rather than be obliged to persuade others to bargain with him, will for ever hinder this from taking place.

The colliers and salters in Scotland were eventually freed by an act of parliament 1775: 15 George 3 c.28 and see above, "Adam Smith and coal."in 1775. But the persistence of slavery in the British colonies, Smith wrote in the Wealth of Nations, could itself be explained by pathological varieties of self-interest. The colonists Smith, The Wealth of Nations, p. 388. "will generally prefer the service of slaves to that of freemen":

the pride of man makes him love to domineer, and nothing mortifies him so much as to be obliged to condescend to persuade his inferiors.

Smith was intensely conscious of the tendency of the owners of capital to impose the costs on other people; of externalities. Of the "depredations" of the English East India Company in Bengal, he wrote Smith, The Wealth of Nations, p. 753.that "in some of the richest and most fertile countries in India," "all was wasted and destroyed." There were pathologies of interest, here as in the Scottish salt mines and the American colonies: it was "agreeable" to the Company that "their own servants and dependents should have either the pleasure of wasting or the profit of embezzling whatever surplus might remain."

This was the point, even, of the famous observation in the Wealth of Nations about the discovery by Europeans of America and the Cape of Good Hope, of which Smith, The Wealth of Nations, p. 626; emphasis added. the "general tendency seems to be beneficial. To the natives, however, both of the East and West Indies, all the commercial benefits which can have resulted from those events have been sunk and lost in the dreadful misfortunes which they have occasioned." These were not environmental externalities. But they were costs imposed by one set of individuals, in the course of the use of their own capital, on other, sometimes distant individuals.

The philosophical or psychological version of the awesome charge about climate change is an empirical hypothesis about the world, as well as an ideological hypothesis about Smithianismus, and it is in this sense less implausible. Was there an epidemic of self-interest in early 19th-century Britain, as so many contemporaries believed they could discern, with successive "waves" almost everywhere else (from the United States to Korea or India)? It is not easy to imagine the evidence for the existence of such epidemics, or for their aetiology. But there was effusive praise for self-interest among the theorists of the early industrial revolution in Britain. There was even the project of an actual industrialist (Robert Owen), a few years after Smith's death; a proposal, Robert Owen, A New View of Society (London, 1813), pp. 13, 42; emphasis in the original text.based on "previous success in remodelling English character," that the working people of Scotland should be trained in "THE HAPPINESS OF SELF CLEARLY UNDERSTOOD AND FULLY COMPREHENDED."

There is almost nothing in Smith's own writings that can help to illuminate the collective psychology of capitalist societies in the generations after his death. He was sceptical of generalizations about national character as it varied across space (as in his comments See above, "Smithian growth."on the probity and commercial virtues of the Dutch), and presumably as it varied over time as well. His own generalizations about the pathologies of self-interest -- the domineering and destruction -- are dispiriting.

The antonyms of self-interest, as described by Smith's 19th-century critics, were religious faith and unreflecting obedience to one's superiors (for Southey and Bonald), and patriotic enthusiasm or deference to the nation state (for the German opponents of Smithianismus.) These were not Smith's values. The effort to induce collective virtues of selflessness -- or even, now, of climate consciousness -- is itself dispiriting, in respect of enlightenment values of freedom of thought.

Smith had faith, in the end, in the mildness and thoughtfulness of most individual men and women, and it is with that prospect that these tricentenary essays will conclude. But his political economy of influence, especially in relation to infrastructure, suggests some of the less encouraging prospects of the new public-private partnerships of our own times, and of the green economy. This is the politics of the conversations about roads, which will be the subject of the next essay.

| « Smithian growth | Conversations about roads » |