Long-distance oppression

Climate change is obdurately unfair. It is something that exists, a material process that is happening, now, in space and time. It has causes and consequences. But the causes are in different places and times from the consequences. There is Robert Owen in Lanark in 1821 (teaching the happiness of self amidst the "extraordinary" powers Robert Owen, Report to the County of Lanark (Glasgow, 1821), pp. 18-19.of the steam engine) and Xiao Jun in Fushun Xiao Jun was the author of Coal Mines in May, a socialist realist novel set in the fictional mining town of Wujin, "a carbon copy of Fushun." Victor Seow, Carbon Technocracy: Energy Regimes in Modern East Asia (Chicago, 2022), pp. 255-257.in 1951 (in the colliery that was once the "coal capital" of China.) There was a "woman of 81 living in Cenon, a suburb on the right bank of the Gironde, who was found dead in her home" during the heatwave https://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2006/07/19/la-canicule-sous-haute-surveillance_796668_3224.htmlof the summer of 2006 in Bordeaux. There are the children of the poor who are withering in New Delhi in June 2023, and who live or die, with their "still developing thermoregulation systems," amidst Rakesh Banerjee and Riddhi Maharaj, "Heat, infant mortality, and adaptation: Evidence from India," Journal of Development Economics, Volume 143, March 2020, 102378.the "highest humidity-indexed mean temperatures."

It is this arbitrariness of climate change -- this injustice, or these vectors of causation, varying across time and space and moral responsibility -- that has made it so easy to think of what is happening as without precedent in history, or outside history, or the end of history. But to realize this is not to be free of the responsibility of thinking historically, about the causes of climate change and about how the choices that were made in the past may or may not be in the process of being repeated now. I even wrote an article myself, almost exactly fifty years ago -- it was called "Illusions about Energy" https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1973/08/09/illusions-about-energy/ and see https://histecon.fas.harvard.edu/climate-loss/autoind.html-- in which I concluded sanctimoniously, of the Nixon administration's investments in alternative energy, that "like the city planning and highway construction and aviation policies of the 1940s and 1950s, present energy decisions could leave a dismal heritage for the twenty- and fifty-year future."

To think historically is also to recognize that other, distant people can or could understand difficult choices. Adam Smith had no idea about the material process by which emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases to the atmosphere affect global temperatures and local weather. He did think about the external social costs that were imposed in the course of long-distance commerce, in particular by the private-public partnerships that he so disliked.

It was evident to Smith's contemporaries, if not to 21st-century commentators, that he was harshly opposed to the system of Atlantic slavery and to the East India Companies, in which so many of his neighbours in Fife, the Oswalds and the Johnstones and the Wedderburns, were engaged. He had "exalted into heroes" the African slaves and "debased into monsters" the American colonists, one critic wrote in 1764; he supported the "dismemberment of the empire," according to another critic in 1776. [Arthur Lee], An Essay, in Vindication of the Continental Colonies of America (London, 1764); Thomas Pownall, A Letter from Governor Pownall to Adam Smith (London, 1776); and see Emma Rothschild, "Adam Smith in the British Empire," in Empire and Modern Political Thought, ed. Sankar Muthu (Cambridge, 2012), pp. 184-198. "All was wasted and destroyed," Smith wrote Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, pp. 752-753.of the East India Company's "depredations" in Bengal; the proprietors were "perfectly indifferent" to the "misery of their subjects," and to the "waste of their dominions." They were distant from the costs, or the misery.

There was even a mechanism for the indifference of distance, as identified in Smith's account of the South Sea Company (which had collapsed in 1720, and of which the reorganization, in 1723, was one of the financial innovations of the first summer of Smith's life.) The mechanism was a double indifference, of distance in space (or in the failure of imagination), as between London and the Spanish colonies, and of the distance of financialized capital. An immense capital had been divided among an immense number of proprietors, in Smith's description, and the outcome of the ensuing "negligence and profusion" was not only mismanagement Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, pp. 741-746.in the Company's own affairs, but also -- and above all -- the imposition of costs on other, distant and future people.

Smith, like so many of his contemporaries -- the cosmopolitans who were so derided by the 19th-century historical economists -- was interested in the arbitrariness of information about distant events, and in the arbitrariness of responsibility. This was a familiar genre of scientific fiction, amidst the new long-distance connections of the time, as when Johann Gottfried Herder, Kant's correspondent in Riga (the source of the flax that was imported to Markinch), asked Johann Gottfried Herder, Auch eine Philosophie der Geschichte (1774; Stuttgart, 1990), p. 70.in 1774, "When has the entire earth ever been so closely joined together, by so few threads? Who has ever had more power and more machines, such that with a single impulse, with a single movement of a finger, entire nations are shaken?" Condorcet, in his eulogy of "conservation, of economy in consumption," surmised that there were no limits to the possibility of converting (mineral) "elements into substances to be used," and imagined Condorcet, "Esquisse d'un tableau historique des progrès de l'esprit humain," vol. 6, pp. 257-258.the moral choices of the enlightened individuals to come; they would know that "if they have obligations to beings who are not yet born, these consist not in giving them existence, but in giving them happiness."

Smith's own dire reverie Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, pp. 136-137.about a distant earthquake, that he added to the Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1761, belonged to this genre:

Let us suppose that the great empire of China, with all its myriads of inhabitants, was suddenly swallowed up by an earthquake, and let us consider how a man of humanity in Europe, who had no sort of connexion with that part of the world, would be affected upon receiving intelligence of this dreadful calamity. He would, I imagine, first of all, express very strongly his sorrow for the misfortune of that unhappy people, he would make many melancholy reflections upon the precariousness of human life, and the vanity of all the labours of man, which could thus be annihilated in a moment. He would too, perhaps, if he was a man of speculation, enter into many reasonings concerning the effects which this disaster might produce upon the commerce of Europe, and the trade and business of the world in general. And when all this fine philosophy was over, when all these humane sentiments had been once fairly expressed, he would pursue his business or his pleasure, take his repose or his diversion, with the same ease and tranquillity, as if no such accident had happened. The most frivolous disaster which could befal himself would occasion a more real disturbance. If he was to lose his little finger to-morrow, he would not sleep to-night; but, provided he never saw them, he will snore with the most profound security over the ruin of a hundred millions of his brethren, and the destruction of that immense multitude seems plainly an object less interesting to him, than this paltry misfortune of his own.

"When our passive feelings are almost always so sordid and so selfish," Smith asked, "how comes it that our active principles should often be so generous and so noble?" The man of humanity in Europe had no connection with the individuals in China, they were people "he never saw," and they were also "his brethren." He would have sacrificed his finger if he could have saved them; to have done otherwise would have been to become the most horrible villain in the history of humanity. But they were not real to him, or part of his own interior life.

The vectors of responsibility in relation to climate change are far more vertiginous than in these cameos of enlightenment science. The causes of human-made climate change are a combination of individual choices and large conditions (capitalism or industrialism or materialism.) They are events of which the consequences unfold over an array of different (subsequent) moments in time, and an array of different places. But their meaning, or their reality, is the outcome, as in 1761, of what we see, who are "our brethren," and with whom we have "some sort of connection."

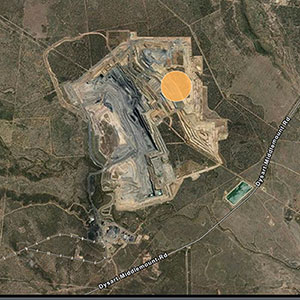

There have been occasions, in the recent history of climate change-related weather, when the (upwards) causal vectors, like emissions of methane to the atmosphere (which cause climate change) have coincided -- in time and space -- with the (downwards) vectors, like the changes in the atmosphere which (probably) cause extreme weather events. The Australian bushfires https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/149039/australian-fires-fueled-unprecedented-bloomsof 2019-2020 killed an estimated 3 billion animals, and scorched millions of hectares of land. They coincided, also in 2019-2020, with an exuberant period of expansion in the Australian coal industry, and of methane emissions from the 62 coal-related sites that were observed from the Sentinel-5 satellite in Queensland and New South Wales, with their evocative industrial names, Dysart and Glennies and Blair Atholl.

![Engraving of the Roman poet Lucretius. Drawn and engraved by Michael Burghers. From the frontispiece to Thomas Creech, T. Lucretius Carus, Of the Nature of Things, second and third editions, Oxford and London 1682–3 Reproduced from the edition by [John Digby], 2 vols., London 1714. (Wikimedia Commons) Engraving of the Roman poet Lucretius. Drawn and engraved by Michael Burghers. From the frontispiece to Thomas Creech, T. Lucretius Carus, Of the Nature of Things, second and third editions, Oxford and London 1682–3 Reproduced from the edition by [John Digby], 2 vols., London 1714. (Wikimedia Commons)](Lucretius.jpg)

This was a false coincidence, in the sense that the particles emitted to the atmosphere from Dysart (QLD) on April 30, 2020 (like the particles emitted by the bushfires themselves) will change the global environment at successive moments over an unknown expanse of future time, and in unknown places, just as the emissions that caused (or contributed to) the bushfires were the outcome of an unknown expanse of past time, and of events in unknown or distant places. (If this sounds like the atomism of ancient philosophy, then it is also Smithian, Smith, Essays on Philosophical Subjects, pp. 42, 92. Vernard Foley, in a study of Smith and Lucretius, concluded that Smith's "hidden cosmology" may have been one of "mechanical materialism," with an interest in "ancient vortex physics." Vernard Foley, The Social Physics of Adam Smith (West Lafayette, 1976), p. 49.as in his "History of Astronomy;" "the supposition of a chain of intermediate, though invisible events," or "the infinite collisions, which must occur in an infinite space filled with matter, and all in motion.")

But the coincidence of news in 2019-2020 was also important. It was something that was visible, for individuals in Australia, and that involved people who were not only their "brethren" -- as the bereaved in China were the brethren of the (imagined) man of humanity in Europe -- but were also individuals with whom they had "some sort of connection." They were individuals, in particular, who were part of the same political society.

Everyone, in our own times of human-induced climate change, has multiple, unexpected connections to other people and to distant places. Some of these connections are political and some are sentimental, or of importance to moral sentiments. Some involve chains of intermediate (or invisible) events over distances in space and time that were unimaginable in Smith's lifetime. They are the outcome of chance encounters, in conversations or in the news (like the "intelligence" about China received by the man of humanity.) But it was these connections -- these relationships to other people -- that were Adam Smith's own enduring preoccupation as he returned to the Theory of Moral Sentiments over the last years of his life. It is to Smith's changing ideas of moral judgement that this birthday celebration will turn, in the concluding installment.

| « Conversations about roads | Sympathy for other people » |