Self-Making Beings

Life, as Lamarck came to see it, was the manifest capacity to create in the face of all nature's forces of destruction. The theory that mortal beings were the creators of the inanimate world was unpopular, to say the least: when Lamarck tried to present it to his colleagues at the National Institute, they interrupted and heckled him so aggressively that he gave up in despair mid-session.

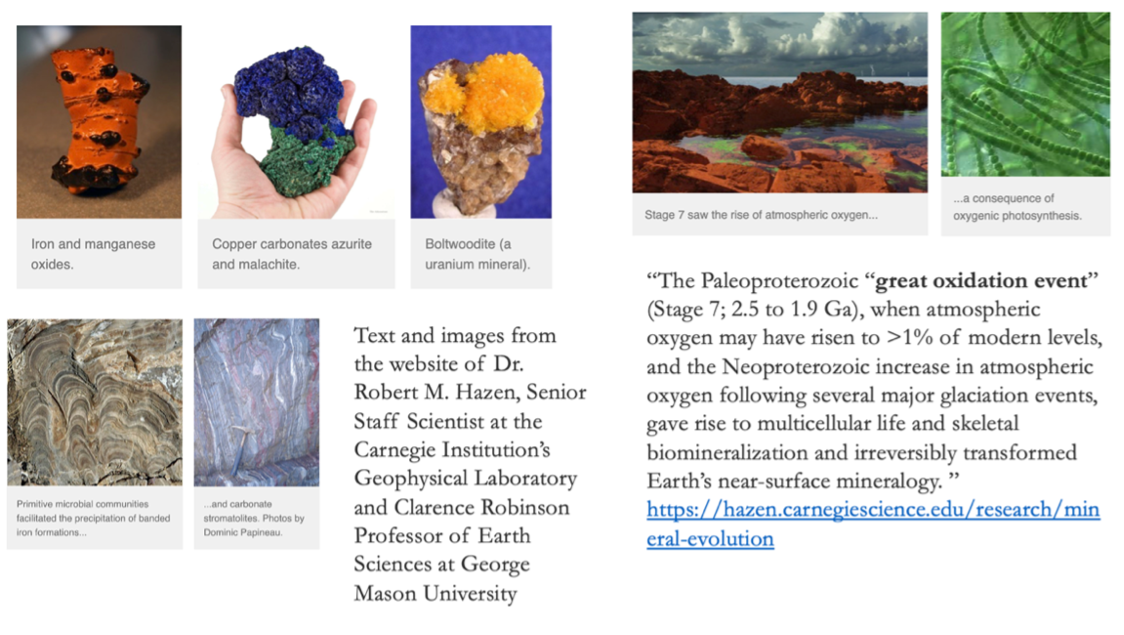

Lamarck, Mémoires, pp. 408-410 and 409 n. 34. His idea of living beings as tragic heroes, striving to create as much of the world as possible before surrendering to their fate, may sound like a Romantic notion, as indeed it was, and Lamarck's theory spent two centuries languishing in exile from mainstream science. Yet recently, the role of organisms in the formation of minerals has inspired renewed interest among geologists. The current scientific consensus is that the first living beings, over 3.5 billion years ago, changed the chemistry of the atmosphere and the oceans, precipitating large-scale mineral deposits; and ever since, organisms have shaped the Earth's surface mineralogy. Geologists studying "mineral evolution" speculate that biological activity may even have helped to stabilize the continents by increasing the rate of granite production. Like Lamarck, these current scientists don't claim to know how the whole process began, but they too believe that for as long as it has existed, life has molded the inanimate world.

Chan, et al., "What Would Earth be Like Without Life?"; Hazen, et al. "Mineral Evolution"; Kennedy, et al., "Late Precambrian Oxygenation"; Kwok, "How Life and Luck Changed Earth's Minerals." Thanks to Carol Cleland and Henderson Cleaves for their guidance in this topic.

Life, as Lamarck came to see it, was the manifest capacity to create in the face of all nature's forces of destruction. The theory that mortal beings were the creators of the inanimate world was unpopular, to say the least: when Lamarck tried to present it to his colleagues at the National Institute, they interrupted and heckled him so aggressively that he gave up in despair mid-session.

Lamarck, Mémoires, pp. 408-410 and 409 n. 34. His idea of living beings as tragic heroes, striving to create as much of the world as possible before surrendering to their fate, may sound like a Romantic notion, as indeed it was, and Lamarck's theory spent two centuries languishing in exile from mainstream science. Yet recently, the role of organisms in the formation of minerals has inspired renewed interest among geologists. The current scientific consensus is that the first living beings, over 3.5 billion years ago, changed the chemistry of the atmosphere and the oceans, precipitating large-scale mineral deposits; and ever since, organisms have shaped the Earth's surface mineralogy. Geologists studying "mineral evolution" speculate that biological activity may even have helped to stabilize the continents by increasing the rate of granite production. Like Lamarck, these current scientists don't claim to know how the whole process began, but they too believe that for as long as it has existed, life has molded the inanimate world.

Chan, et al., "What Would Earth be Like Without Life?"; Hazen, et al. "Mineral Evolution"; Kennedy, et al., "Late Precambrian Oxygenation"; Kwok, "How Life and Luck Changed Earth's Minerals." Thanks to Carol Cleland and Henderson Cleaves for their guidance in this topic.

On the 21st day of the month of Floréal in the Year Eight of the Republic (a.k.a. May 11th 1800), an international group of sixty-four students – one from as far away as Brazil and another from the United States – assembled for what surely promised to be a routine event, the opening lecture of Lamarck's course on invertebrates.

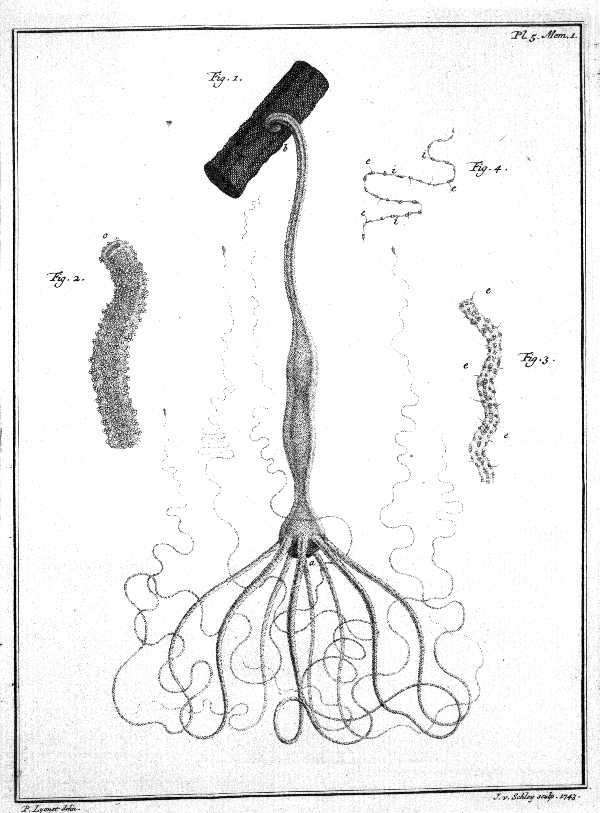

Bange and Corsi, "Les auditeurs" [Joseph Barboza from Brazil; Benjamin Franklin Harris from the US]. Instead, they became participants in an extraordinary moment, as Lamarck presented for the very first time his radical idea that living beings could create and transform not only the inanimate world around them, but even their own selves. Polyps, the simplest of the invertebrates, he told them, embodied the very "limit of animalization" – a rudimentary minimum of animal life – and were perhaps those beings "with whom nature began." This "limit" or "minimum" or essence of animality was none other than the unbridled power of generation. Snails could grow new heads, crustaceans new legs, starfish new rays; coral polyps multiplied by a perpetual budding, forming plant-like stems. The tiniest and simplest animals displayed a "frightening fecundity" as if "matter animalizes itself from every direction."

Lamarck, Discours d'ouverture … 21 floréal an 8, pp. 12-13.

On the 21st day of the month of Floréal in the Year Eight of the Republic (a.k.a. May 11th 1800), an international group of sixty-four students – one from as far away as Brazil and another from the United States – assembled for what surely promised to be a routine event, the opening lecture of Lamarck's course on invertebrates.

Bange and Corsi, "Les auditeurs" [Joseph Barboza from Brazil; Benjamin Franklin Harris from the US]. Instead, they became participants in an extraordinary moment, as Lamarck presented for the very first time his radical idea that living beings could create and transform not only the inanimate world around them, but even their own selves. Polyps, the simplest of the invertebrates, he told them, embodied the very "limit of animalization" – a rudimentary minimum of animal life – and were perhaps those beings "with whom nature began." This "limit" or "minimum" or essence of animality was none other than the unbridled power of generation. Snails could grow new heads, crustaceans new legs, starfish new rays; coral polyps multiplied by a perpetual budding, forming plant-like stems. The tiniest and simplest animals displayed a "frightening fecundity" as if "matter animalizes itself from every direction."

Lamarck, Discours d'ouverture … 21 floréal an 8, pp. 12-13.

Lamarck explained that nature created living forms using two principal means: "time and circumstances." The first of these, time, had "no limit." (Just minutes into what they may have expected to be a dry lecture on the tiniest and most mundane of creatures, the students were plunged into an endless abyss of time.) Circumstances, meanwhile, included climate, temperature, and the particularities of place, but the crucial circumstantial factor was the myriad, creative responses of living beings to the varying conditions in which they found themselves - their habits, their ways of living and surviving. By acting, moving, and responding, animals dynamically shaped and reshaped themselves, expanding and strengthening their parts and organs from generation to generation. For instance, the waterbird created webbed feet for itself by its habit of "spread[ing] its toes when it wants to hit the water to move along the surface"; birds who perched in trees developed hooked talons by curving their toes "to embrace the branches"; and shore birds, unable to swim, elongated their legs as they waded deeper into the sea and stretched to keep their bodies above the water. Lamarck, Discours d'ouverture … 21 floréal an 8, pp. 13-14.

The momentous moral of the story that Lamarck told his students that day was that the evident fitness of animals' bodies to their circumstances arose from their own actions "entirely." "I will be able to prove," he promised, "that it is not the form, either of the body or of its parts, that gives rise to the habits," but just the reverse: the habits gave rise to the form of the body.

Lamarck, Discours d'ouverture … 21 floréal an 8, pp. 15. See also Lamarck, Hydrogéologie, p. 188. Through their behaviors and ways of life, animals had created – and were continually recreating – themselves. This was a shocking assertion in a world where divine creation was the generally acknowledged source of living beings; and today too, Lamarck's claim will probably seem outrageous to anyone who has taken high school biology, since it's at odds with the dominant tradition in evolutionary biology for the last century and a half. Even when Lamarck was first presenting his theory of self-making and world-making living beings, his critics were consolidating their position. Yet his ideas, which have lately been returning to currency, did also gather worldwide attention and interest during his lifetime.

The momentous moral of the story that Lamarck told his students that day was that the evident fitness of animals' bodies to their circumstances arose from their own actions "entirely." "I will be able to prove," he promised, "that it is not the form, either of the body or of its parts, that gives rise to the habits," but just the reverse: the habits gave rise to the form of the body.

Lamarck, Discours d'ouverture … 21 floréal an 8, pp. 15. See also Lamarck, Hydrogéologie, p. 188. Through their behaviors and ways of life, animals had created – and were continually recreating – themselves. This was a shocking assertion in a world where divine creation was the generally acknowledged source of living beings; and today too, Lamarck's claim will probably seem outrageous to anyone who has taken high school biology, since it's at odds with the dominant tradition in evolutionary biology for the last century and a half. Even when Lamarck was first presenting his theory of self-making and world-making living beings, his critics were consolidating their position. Yet his ideas, which have lately been returning to currency, did also gather worldwide attention and interest during his lifetime.

For a quarter century, walking across the garden from his residence to the graceful, neoclassical Verniquet Amphitheater where he gave his lectures, Lamarck unfolded, for the generations of students who came from all over the world to hear him, this process of mortal creation. His lectures were so popular that even fictional characters attended them. In his autobiographical novel Volupté, the Romantic author and literary critic Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve sent his lightly fictionalized doppelgänger, the lovelorn young Amaury, to Lamarck's course. In Amaury's voice, Sainte-Beuve offered an evocative description of what it was like to sit in the Verniquet Amphitheater and listen as Lamarck spoke. He described the "passionate and almost painful tone" in which Lamarck raised "serious primordial questions." Lamarck's worldview, he said, "had much simplicity, starkness, and much sadness. … According to him, things made themselves by themselves, all alone in continuity." Sainte-Beuve, Volupté, Vol. 1, pp. 227-230.

| « Mortal Creation | Imperial Scorn » |