Mortal Creation

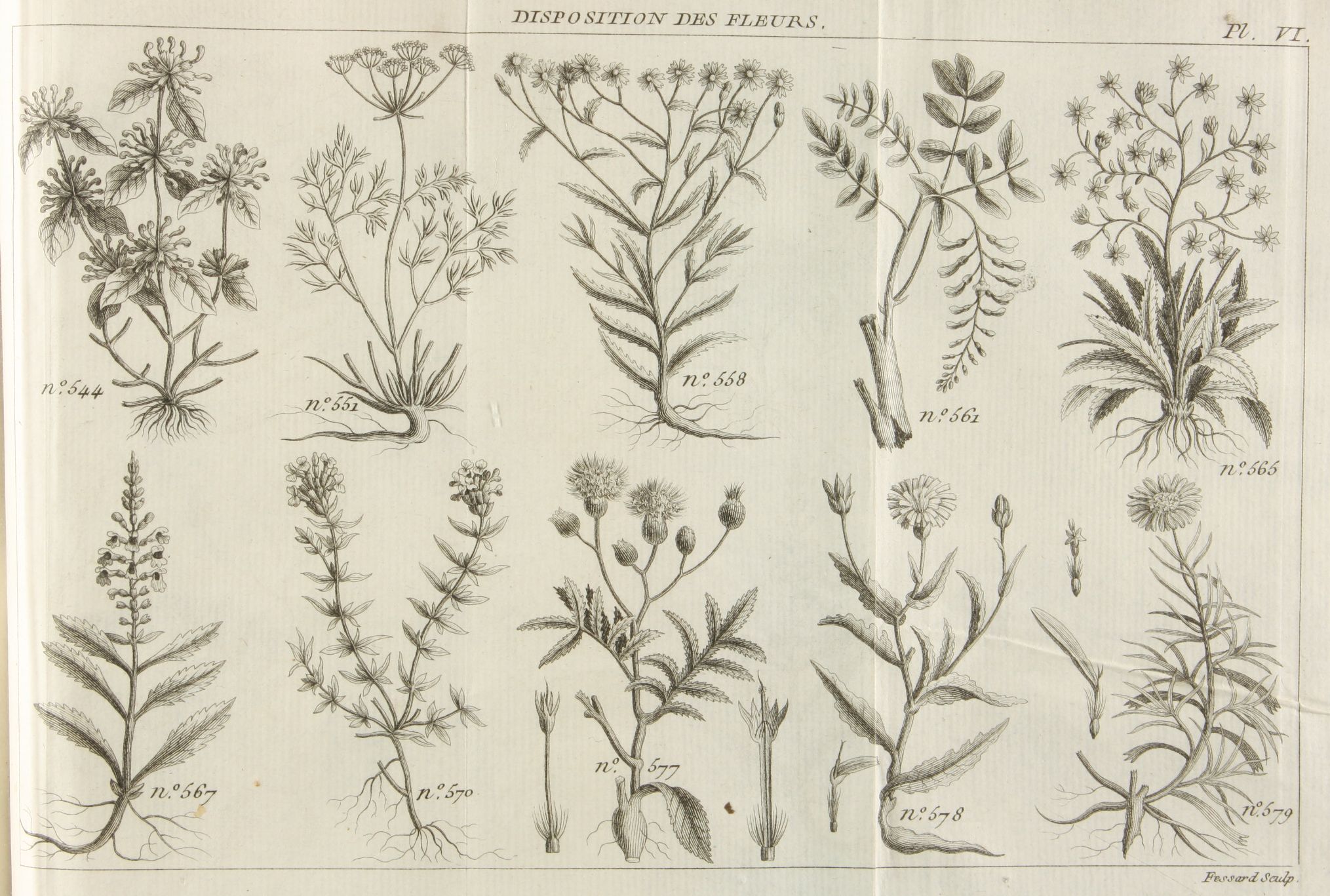

Lamarck had launched his career as a naturalist in the spring of 1779 by publishing a three-volume work on Flore française featuring the scandalous idea that plants had sex: that flowers were in fact sex organs, the stamens comparable to testes and the pistils to ovaries. Not only did plants have sex, Lamarck wrote, but this was the very thing that distinguished them, as organic beings, from minerals. He rhapsodized about the flowers' "sweet perfumes" and "laughing and lively" demeanor. While the self-centered human observer might think these lovely sights and smells were all intended just for him, Lamarck chided, in fact, flowers were not meant to please humans, but to beguile other plants. Lamarck, Flore française, Vol. 1, pp. 2, 103-105.

Lamarck's Flore française caught the notice of Georges Buffon, who was then director of the Jardin du Roi, and who made Lamarck his protégé, maneuvering to get him appointed as an adjunct member of the Academy of Sciences, arranging for Flore française to be printed by the royal printer at the government's expense, and helping Lamarck to prepare the work for publication.

Lamarck's Flore française caught the notice of Georges Buffon, who was then director of the Jardin du Roi, and who made Lamarck his protégé, maneuvering to get him appointed as an adjunct member of the Academy of Sciences, arranging for Flore française to be printed by the royal printer at the government's expense, and helping Lamarck to prepare the work for publication.

Flore française also sold well enough to bring Lamarck a bit of extra money, which he used to organize an expedition in search of rare plants with two friends of about his own age, in their early thirties, both named André: André Thouin, who had been chief gardener in the King's Garden since the age of seventeen, having inherited the job from his father; and André Michaux, a fellow botany student of Lamarck's who would go on to a career as a botanist and explorer. Lamarck and the two Andrés traveled to the Auvergne region in south central France, where they explored the volcanic Massif Central highlands around the Puy de Dôme, a mountain of lava; they investigated the Mont-Dore area, where the thermal springs provided an ancient Gallo-Roman spa town; and they perused the lush plateaus and river valleys of the Cantal range. Lamarck, "Considerations," 2; Cuvier, "Eloge," 8-11; Bourdon, "Lamarck," 344; Bourguin, "Lamarck," 199-201.

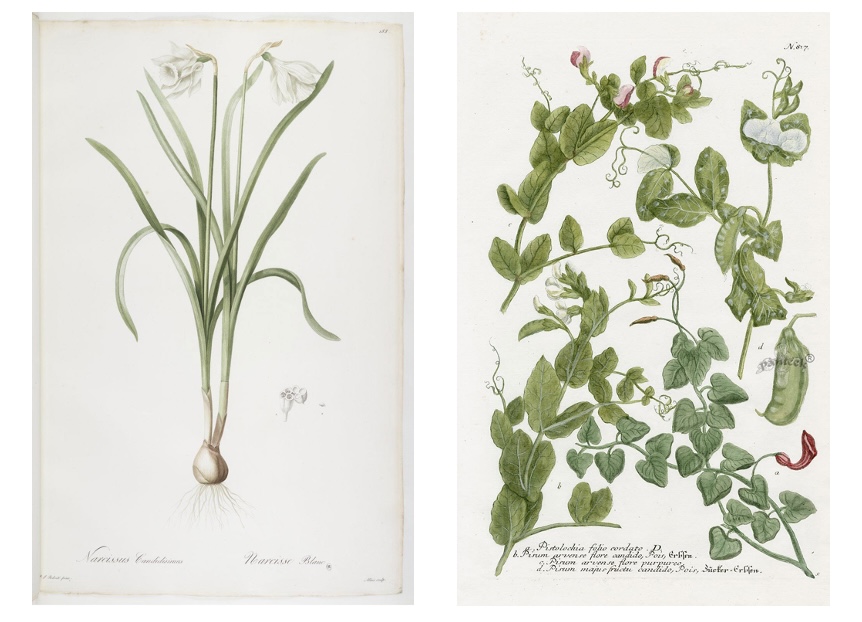

During this trip, Lamarck contemplated another scandalous idea that he was working on: that living things actually created the inanimate world, composing it from elements. He surmised that "minerals," by which he meant inanimate, compound matter, arose from the actions of living beings. Plants played the primary role in this process because they could produce themselves from just sunlight, air, and water. Their substance then became the primary matter for animals and natural forces, such as heat and gravity, to act upon, transforming it further into animal and mineral matter. Plants therefore supplied the first stage of compound matter for making minerals. Lamarck proposed an easy experiment to demonstrate plants' ability to do this: suspend a hyacinth or narcissus bulb in a carafe of distilled water and you'll see it grow an entire flowering plant. This, when weighed, will prove much heavier than the original bulb, proving that it has actually created matter.

Lamarck, Recherches sur les causes, Vol. 2: ¶822, p. 292; ¶830, pp. 296-297.

During this trip, Lamarck contemplated another scandalous idea that he was working on: that living things actually created the inanimate world, composing it from elements. He surmised that "minerals," by which he meant inanimate, compound matter, arose from the actions of living beings. Plants played the primary role in this process because they could produce themselves from just sunlight, air, and water. Their substance then became the primary matter for animals and natural forces, such as heat and gravity, to act upon, transforming it further into animal and mineral matter. Plants therefore supplied the first stage of compound matter for making minerals. Lamarck proposed an easy experiment to demonstrate plants' ability to do this: suspend a hyacinth or narcissus bulb in a carafe of distilled water and you'll see it grow an entire flowering plant. This, when weighed, will prove much heavier than the original bulb, proving that it has actually created matter.

Lamarck, Recherches sur les causes, Vol. 2: ¶822, p. 292; ¶830, pp. 296-297.

A similar experiment used a turnip: carve a small hollow in its side and suspend it in the air by its root, Houdini-style – nothing up its sleeves! Keep the hollow filled with water and again you'll see it grow and create flowers. Some people he knew, Lamarck reported, liked to raise peas in earthenware dishes with just pure water and cotton wool to support the roots, lending greenery to their apartments during wintertime. He himself was then living in a small apartment near the Jardin du Roi with his wife and two young children; perhaps they liked to brighten the dark, gray Parisian winter by watching decorative pea plants unfurl themselves from earthenware dishes, conjuring their delicate, pale green tendrils from thin air. Lamarck, Recherches sur les causes, Vol. 2: ¶830, pp. 296-297 ; ¶832, pp. 298-99.

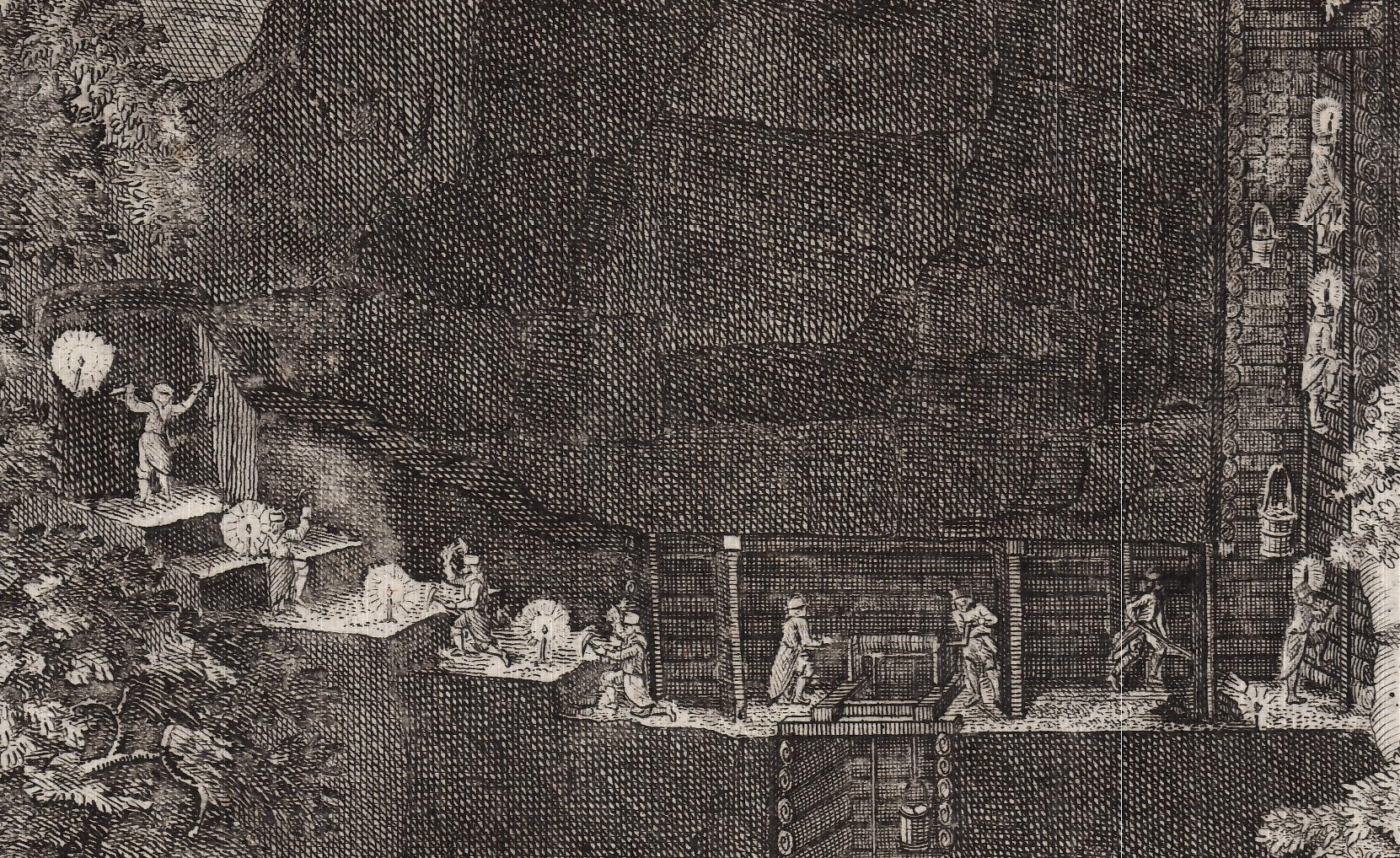

Two years later, during the spring and summer of 1781, Lamarck left Paris again on a journey of several months, this time as the escort of Buffon's obstreperous seventeen-year-old son, Georges, nicknamed Buffonet. Buffon wanted to educate young Buffonet as a naturalist so that he could bequeath to him the directorship of the King's Garden, and he chose Lamarck as the boy's mentor. Together, Lamarck and Buffonet visited the botanical gardens, mines and quarries of central Europe, bringing along letters of introduction from Buffon to monarchs, nobles, and naturalists. Exploring the mines, Lamarck gathered evidence to support his radical new idea that all minerals arose from the actions of living beings, from their remains and the other debris they produced. "In one of the mines of Freyberg in Saxony, where I went down, I found manifest proof," Lamarck triumphantly reported.

Lamarck, "Classes," pp. 35. See also Lamarck, Recherches sur les causes, Vol. 2: ¶¶939-943, pp. 371-373. Descending through the layers, he could see that with the passage of time and under the heat and pressure of the earth, the organic material at the surface changed into ever harder and less organic mineral compounds. "I have constantly noticed [this] in all the mines where I have been down," he wrote. He carried back to Paris some transitional specimens that he believed revealed the passage from organic to mineral matter, for instance, some pectin, a starchy plant fiber, "graduating from the most obvious clayey state to a completely glassy state."

Lamarck, Recherches sur les causes, Vol. 2: ¶¶939-943, pp. 371-373, cited passages in ¶940, p. 372 and ¶¶942-943, p.373.

The trip was productive for Lamarck, but it wasn't easy: one day, when Buffonet wanted to go out alone without his highly conscientious escort, he deliberately splattered ink all over Lamarck's clothes. Lamarck still resented this childish act of rebellion almost forty years later when he recounted the story to a visitor. Buffon, reading between the lines of the letters he received, gathered that the situation had deteriorated and recalled the travelers to Paris, where Lamarck could continue contemplating his new ideas about the natural world in peace. Bourdon, "Lamarck," p. 343-44; Bourgin, "Lamarck," 199; Landrieu, Lamarck, 31.

The remarkable ability to merge elements into compounds was unique to plants, he now affirmed, since no animal could subsist on just air, sunlight, and water. Plants therefore originated the cosmic relay chain, bringing together the primitive elements and handing the combinations off to animals. Then animals, by eating and digesting, turned plants and other animals into more complex compounds, and so shared with plants the defining ability of living beings: to build, compose, and create. Lamarck, Recherches sur les causes, Vol. 2: ¶827, p. 294-95.

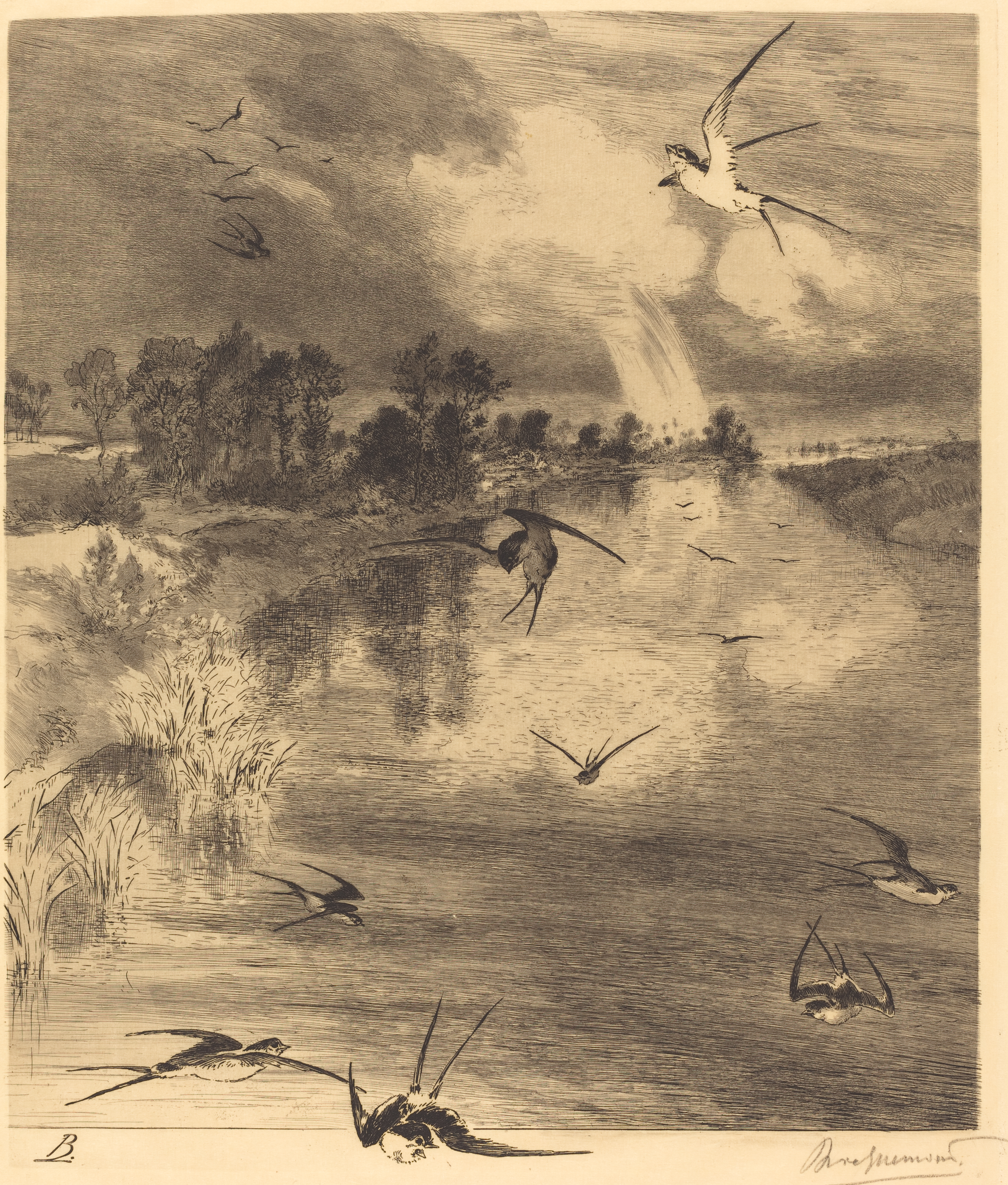

This work of world-making was mortal rather than divine, according to Lamarck, and it was also collaborative rather than solitary. He took a keen interest in this aspect, observing it wherever he went. He told a charming story about the collaborative tendencies of living things that took place at a house he briefly owned in the Pays de Bray, a region of pastures and woodlands in northwest France. One day in the spring of 1798, when Lamarck went up to the house with his family, he noticed a swallow's nest in one of the windows. Shortly afterwards, a local child destroyed the nest, leaving the pair of swallows homeless just as the female was about to lay her eggs. Immediately, ten or twelve other swallows gathered around the wreckage. The birds were so agitated and noisy that at first Lamarck assumed they were quarreling, but he soon realized it was just the opposite: they had organized themselves to rebuild the nest collaboratively. He watched in amazement as some remained by the construction site while others came and went in rapid succession. Swallows generally take eight to twelve days to build their nest, Lamarck observed, but these worked so diligently that they finished it the following morning. Lamarck offered this story to his friend and colleague Géoffroy Saint-Hilaire for his collection of instances of mutual affection and helpful services rendered among animals, thereby himself exhibiting the very quality Géoffroy was keen to document. Géoffroy Saint-Hilaire, "Observations," p. 471, n. 2."

The story of the collaborative swallows was Lamarck at his most optimistic. But a distinct note of tragedy penetrates his worldview, since of course all living things are doomed to ultimate failure. The inevitable end comes, he said, when an animate being loses that "astonishing principle" which has hitherto allowed it to sustain itself against the onslaught of nature, continually dragging it towards its ruin. When living things die, Lamarck explained that they surrender all they have made in a lifetime – their bodies, secretions, and other productions – to the forces of nature, which then act upon these products, putting them through various destructive transformations, producing a succession of minerals, which make up the clay of the composed world.

Lamarck, Recherches sur les causes, Vol 2: ¶818, pp 289-90 ("drags it towards its ruin"); Vol. 1, p. 2 ("alternating succession of life and death"). See generally Vol. 2: ¶¶70-792, pp. 273-275; and Vol. 2: ¶¶808-822, pp. 284-292. "What must be our astonishment," Lamarck exclaimed, upon learning that the tiniest and simplest of creatures, the madrepore and millepora coral polyps have been the chief producers of the great calcareous mountain chains and enormous banks of chalk found all over the earth? With some help from shellfish, these minuscule animals together create islands, fill up bays and gulfs, clog ports and shape coastlines.

Lamarck, Système des animaux, pp. 24-25.

The story of the collaborative swallows was Lamarck at his most optimistic. But a distinct note of tragedy penetrates his worldview, since of course all living things are doomed to ultimate failure. The inevitable end comes, he said, when an animate being loses that "astonishing principle" which has hitherto allowed it to sustain itself against the onslaught of nature, continually dragging it towards its ruin. When living things die, Lamarck explained that they surrender all they have made in a lifetime – their bodies, secretions, and other productions – to the forces of nature, which then act upon these products, putting them through various destructive transformations, producing a succession of minerals, which make up the clay of the composed world.

Lamarck, Recherches sur les causes, Vol 2: ¶818, pp 289-90 ("drags it towards its ruin"); Vol. 1, p. 2 ("alternating succession of life and death"). See generally Vol. 2: ¶¶70-792, pp. 273-275; and Vol. 2: ¶¶808-822, pp. 284-292. "What must be our astonishment," Lamarck exclaimed, upon learning that the tiniest and simplest of creatures, the madrepore and millepora coral polyps have been the chief producers of the great calcareous mountain chains and enormous banks of chalk found all over the earth? With some help from shellfish, these minuscule animals together create islands, fill up bays and gulfs, clog ports and shape coastlines.

Lamarck, Système des animaux, pp. 24-25.

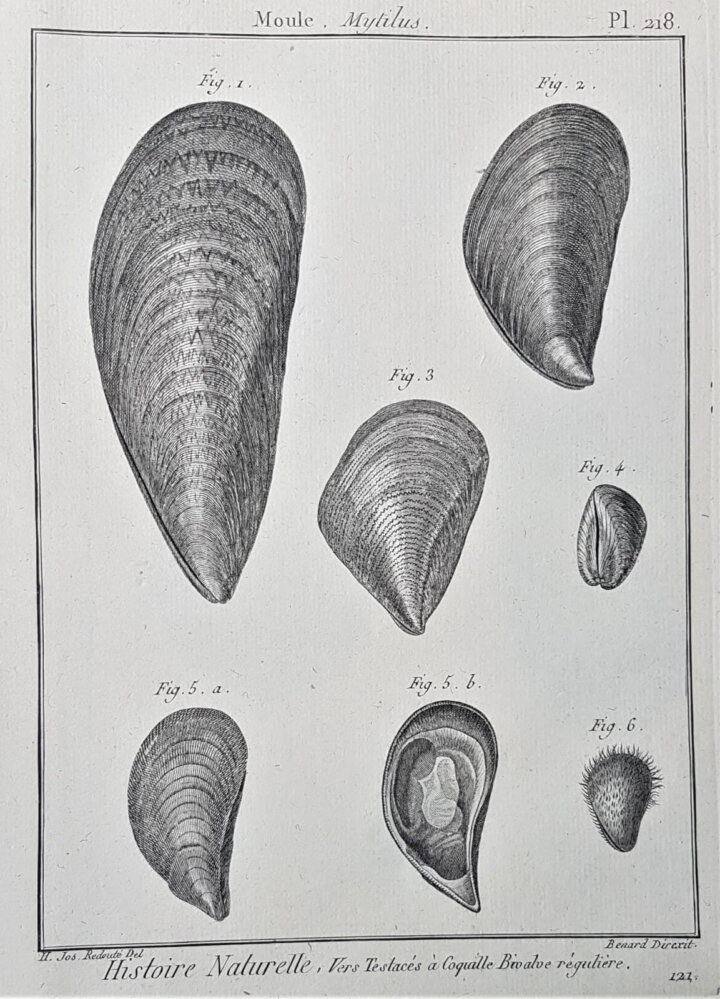

Lamarck was fascinated by shellfish; since arriving in Paris, he had been working on a collection of shells that grew to become one of the biggest and most beautiful

Lamarck, Système des animaux, p. vii; BMHN Mc 93, Lamarck – Lucien Bonaparte, 7 brumaire an 9 [19 October 1800]; Bourdier and Orliac, "Esquisse," 26-27, 33.in the city. This was a fashionable pursuit and an expensive one, but he probably struck a deal with some Parisian shell merchants, trading his growing knowledge for occasional rare specimens. Shells had been his only area of zoological expertise before the National Convention made him a zoologist, but it proved to be a very relevant one when he became responsible for "worms" and decided mollusks – along with several other sorts of "worms" – deserved their own, separate category among what he called the "invertebrates."

Lamarck, Philosophie zoologique, Vol. 1: 122-24. Then, two years after the political bouleversement that turned Lamarck into a zoologist, another upheaval turned him back into a botanist again: in the summer of 1795, having earlier abolished all the learned academies, the National Convention re-created them as divisions of a single National Institute and appointed Lamarck to the Botany section.

Landrieu, Lamarck, 87. Still, Lamarck remained an invertebrate zoologist at the Museum of Natural History in the Jardin des Plantes. He continued to integrate botany and zoology into his general theory of life, working from both perspectives at once to develop his idea that plants and the simplest animals played the foundational roles in creating the world.

Lamarck was fascinated by shellfish; since arriving in Paris, he had been working on a collection of shells that grew to become one of the biggest and most beautiful

Lamarck, Système des animaux, p. vii; BMHN Mc 93, Lamarck – Lucien Bonaparte, 7 brumaire an 9 [19 October 1800]; Bourdier and Orliac, "Esquisse," 26-27, 33.in the city. This was a fashionable pursuit and an expensive one, but he probably struck a deal with some Parisian shell merchants, trading his growing knowledge for occasional rare specimens. Shells had been his only area of zoological expertise before the National Convention made him a zoologist, but it proved to be a very relevant one when he became responsible for "worms" and decided mollusks – along with several other sorts of "worms" – deserved their own, separate category among what he called the "invertebrates."

Lamarck, Philosophie zoologique, Vol. 1: 122-24. Then, two years after the political bouleversement that turned Lamarck into a zoologist, another upheaval turned him back into a botanist again: in the summer of 1795, having earlier abolished all the learned academies, the National Convention re-created them as divisions of a single National Institute and appointed Lamarck to the Botany section.

Landrieu, Lamarck, 87. Still, Lamarck remained an invertebrate zoologist at the Museum of Natural History in the Jardin des Plantes. He continued to integrate botany and zoology into his general theory of life, working from both perspectives at once to develop his idea that plants and the simplest animals played the foundational roles in creating the world.

| « Introduction | Self-Making Beings » |