A Life-Made World

From the start, Lamarck's science of self-making, world-creating living beings antagonized the powerful. In contrast, the dominant tradition in evolutionary biology that took hold by the end of the nineteenth century, and whose reign abides for the most part still today, renders living organisms as the fundamentally passive objects of outside forces, powerless to threaten gods or monarchs or other worldly powers. Evolutionary science became the reductive account of an essentially passive living world. By this standard, Lamarck's vision of a world continually in the making by its own mortal inhabitants wasn't even wrong: it just wasn't science.

Recently, though, Lamarck's worldview and mode of science have shown signs of re-emerging. Biologists have been collecting evidence of living beings remaking themselves. To take just one small example, marine biologists have recently found that the spiny chromis, a slender damselfish inhabiting the coral reefs of the Pacific, is responding to the higher water temperatures brought on by climate change by transforming its metabolism in myriad ways, and that these changes are inherited from generation to generation. The changes aren't in the damselfish's DNA: they're "epigenetic," meaning they occur outside the genome and involve factors that influence gene-expression, the ways in which sequences of DNA encode the production of the proteins that make up the body. Still, by transforming itself in response to global warming and passing these changes on to its offspring, the spiny chromis influences the course of natural selection and, therefore, the DNA of future generations. Ryu et al., "The Epigenetic Landscape."

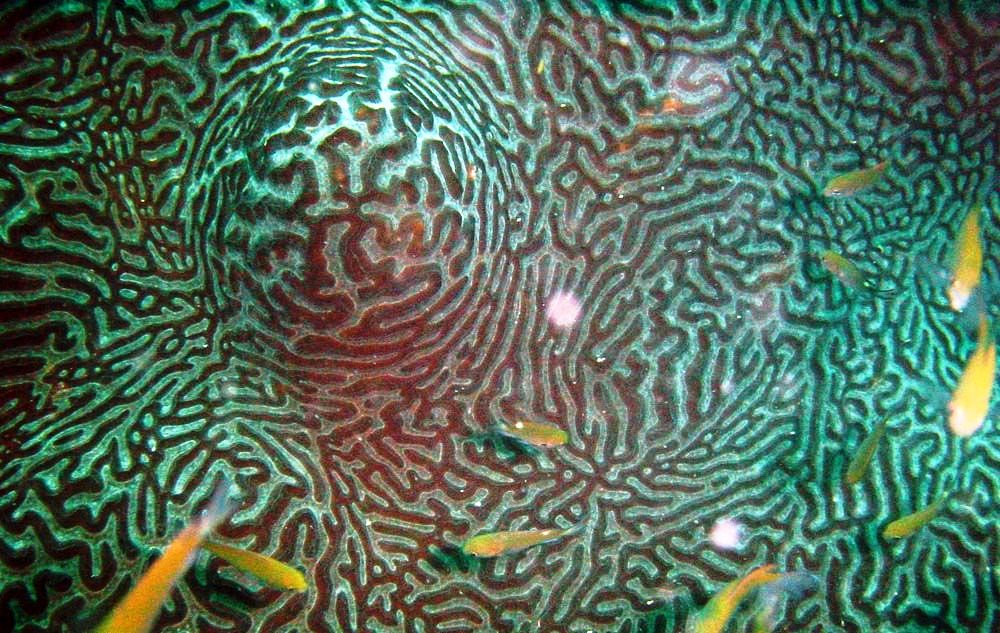

The spiny chromis isn't alone. Scientists in Australia have recently found that the reef-building coral providing the damselfish's home also responds to changing ocean temperatures and salinity with epigenetic changes that it passes on to its offspring. Liew et al., "Intergenerational Epigenetic Inheritance." In fact, it seems increasingly apparent that all living beings respond to their changing environments with epigenetic transformations that can be inherited. Jablonka, "Evolutionary Implications." German evolutionary geneticists have found that wild guinea pigs respond to heat-stress by heritably altering their livers, which play a crucial role in metabolic regulation; biologists in the United States and Kenya have shown that baboons also heritably change their metabolisms in response to differences in their food supply.Weyrich, et al., "Environmental Change-Dependent Inherited Epigenetic Response"; Lea, et al., "Resource Base Influences." The field of epigenetics is young but already scientists have gathered examples throughout all forms of life – bacteria, fungi, protozoans, plants, invertebrates, fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals – to suggest that epigenetic inheritance is ubiquitous, and inseparable from genetic inheritance. In short: Lamarck was right. The delicate, resourceful damselfish and a growing list of other organisms exemplify what he knew and mainstream evolutionary biology has until recently categorically denied: living beings are active, creative, self-making, world- making.

Not only was Lamarck right about this, but it's a matter of urgent importance. Denying the agency of living beings – treating them as the passive objects of external forces – has not been a purely intellectual mistake. It has informed two centuries of environmental destruction, as people have regarded the living world as so much raw material to exploit for economic, industrial and imperial gain. Lamarck, who witnessed the Industrial Revolution firsthand, warned of this. I began this essay with a passage from his last work, written in 1820 when he was infirm, blind, dismissed and ridiculed by most of the powerful figures in science and politics. He wrote in a fit of despondency that people were selfish and short-sighted, careless for the future, wantonly annihilating their own means of conservation, and working toward the destruction of their own species and of all living things. Perhaps he was thinking of the mines and quarries he had toured with Buffonet; and, no doubt, of their ever-accelerating growth in the intervening decades. He pointed out deforestation and its consequences: destroying the trees and large plants that protected the soil to "satisfy the greed of the moment, [man] quickly brings sterility to this soil … causes the springs to dry up, drives away the animals who found their subsistence there, and causes great parts of the globe, once very fertile and highly populated, to now be bare, barren, uninhabited and deserted." Human beings' passions led them to ignore experience, to carry on waging wars and plundering nature for riches. "It looks like man is destined to exterminate himself after making the globe uninhabitable," Lamarck concluded despairingly.Lamarck, Système analytique, pp. 154-55.

Alas, it seems he was right about most of this, but let's hope not all of it. If a more Lamarckian worldview is on the rise again – a view of the world as continually being made and re-made by all living beings in concert – perhaps it could improve our chances of remaking ourselves in time to allow the living world to carry on creating itself.

| « Imperial Scorn | Works Cited » |