Kelp

By the time Thomas Malthus published the gloomy prognostications of his Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798, the rulers of Tiree had already long fretted over the rising number of inhabitants and their meagre means of sustenance. The island was obviously limited, its tillage already extensive, and even if they felt there was great scope for the improvement of its harvests, there was little expectation of that supporting every household.

Yet an island does not only subsist on itself. It lives intimately with its surroundings. In Tiree’s case, the harvest of the sea, or more accurately, that tidal interzone between low and high water, was already boosting the fertility of its soils, while its dissolving salts punished weeds – landlubbing weeds. For Tiree already subsisted on the weeds of the sea.

Humble seaweed would transform the settlement and fortunes of the island. Just as barley could be transformed into whiskey, so could seaweed undergo a metamorphosis through fire that made the storm-cast tangle of a Hebridean strand a highly desired product for the vanguard of industrialisation. Seaweed became kelp, and kelp was hot property.

The kelping industry tied the people of Tiriodh to industrial plant in Ulster’s Lagan valley, to the mighty entrepôt of Liverpool, to the glassmakers of Tyneside. It made the crofts of Balemartine and Ruaig as much as part of the Industrial Revolution as the spinning mills and steam engines. But it could do so because, ironically, it extended the old ways of collective agriculture. Long since, when the sub-tenants of farms gathered to put their ploughteams to work in the spring, scores of ponies would be sent to the shore with baskets to collect ‘sea ware’ to cast on the turned earth. Demand for kelp could extend this seaweed season, especially for cottars and those short on work in agriculture. In 1791 the factor reported kelp being made, without a trace of irony, by ‘idle people’. Alongside the potato beds which could also be sustained by repeated applications of ware (as seaweed was usually called), a means had been found for the poor to eke out a living from tiny plots of land, whilst providing labour when needed to larger farms – one reason why the cottars were tolerated. In turn, kelp could pay the rent when the authorities turned the screw on distilling.

The kelping industry tied the people of Tiriodh to industrial plant in Ulster’s Lagan valley, to the mighty entrepôt of Liverpool, to the glassmakers of Tyneside. It made the crofts of Balemartine and Ruaig as much as part of the Industrial Revolution as the spinning mills and steam engines. But it could do so because, ironically, it extended the old ways of collective agriculture. Long since, when the sub-tenants of farms gathered to put their ploughteams to work in the spring, scores of ponies would be sent to the shore with baskets to collect ‘sea ware’ to cast on the turned earth. Demand for kelp could extend this seaweed season, especially for cottars and those short on work in agriculture. In 1791 the factor reported kelp being made, without a trace of irony, by ‘idle people’. Alongside the potato beds which could also be sustained by repeated applications of ware (as seaweed was usually called), a means had been found for the poor to eke out a living from tiny plots of land, whilst providing labour when needed to larger farms – one reason why the cottars were tolerated. In turn, kelp could pay the rent when the authorities turned the screw on distilling.

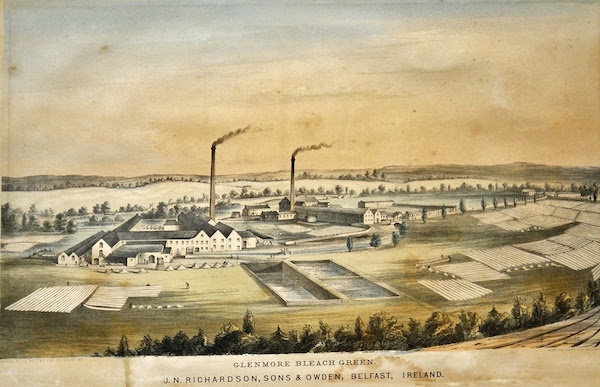

It was the Irish that first developed a kelping industry on any scale. The driver was the needs of bleachers for alkalis in the burgeoning industry of Ulster that prepared the finest linens and cambrics for an international market, especially from the 1740s. John Walker thought that Irishmen had brought kelping to Tiree in 1746, a first landfall in the Hebrides. Soon the islands’ wares were considered superior to all others, carried to the wharves of Belfast and Newry, or the north-east of England. Tenants and cottars seem to have first developed the industry on a modest scale, in combination with Highland merchants and sea-captains. By the 1760s, Tiriodh produced around 44 tons per year, processed from up to 1 000 tons of seaweed.

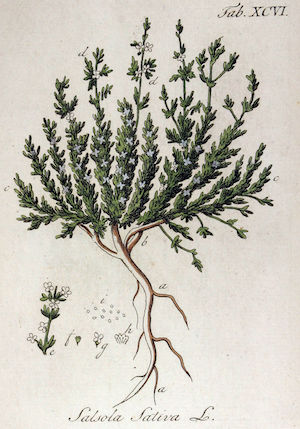

It was after 1780 that the industry transformed and became transformative. One reason was the enormous expansion in demand as industrial production took off. The other reason was political economy. Kelp was valuable for the alkalis it contained, and these could be substituted by potash (made from wood ash in Russia or North America) or barilla (from the region around Alicante in Spain), an ‘earthy shrub that bears berries like barberries’ that was fired in a pit over days to produce a hard blue residue. From 1780 the government placed duties on barilla and by the 1790s supplies of kelp’s competitors plunged with the onset of war. Just as the revolutionary war protected the Atlantic market for Britain, more than ever it tested Britain’s mettle in living off its imperial resources. This was kelp’s moment, and for three decades it made Hebridean seaweed an ineluctable adjunct of the Industrial Revolution.

Kelp retailed for £2 per ton around 1750. The American war pushed it up to £8. By the turn of the century it reached £10, and in 1810, a previously unimaginable £20. By some alchemy the pungent wrack of the shore had become a precious seam to be mined. The Highland and Islands were sending 20 000 tons of kelp south each year – the produce of getting on for half a million tons of seaweed hauled from the waves on Scotland’s shores.

Of course war times are expensive times. In the galloping inflation of the 1790s and 1800s, keeping up appearances became no easier for Highland magnates, even as they enjoyed with other landowners the buoyant rents of the late eighteenth century. By 1790, it was dawning on the 5th Duke that kelp was a resource from which he was not reaping the benefits. It led to an astonishing, and deeply consequential, reversal in policy.

Since 1771 the Duke and his chamberlains had been attempting to consolidate the sub-tenanted farms of Tiriodh into fewer large holdings for tillage or, notoriously at this time, sheep farms. Yet it was fiercely resisted by the tenantry, for what would be done with the supernumerary populace? The alternatives were planned fishing villages on the southern shore, or emigration. Yet when he fully grasped the potential upward trend of kelp prices, and that precisely because of kelping smaller tenants could bear a higher rent than large farms, the Duke instigated a new policy: crofts. Inland farms would be cleared, but the population concentrated near the shore with the promise of new housing, smallholdings for a little tillage and potatoes and some pasture, and the opportunity of kelping alongside a secure tenure. Crofting, so long considered the Highland life par excellence, was born of the bleachgreens of Ulster and the soapboilers of the Mersey. Previously focused at the east end of the island, kelping spread all around its shores and after 1800 a crofting settlement of almost 40 properties sprang up at Balemartine, still today the largest village on the island.

In 1770-1, Tiriodh had paid £852 in rent from the barley it grew and sales of whiskey. In 1805-6 it paid the Duke £2 606, entirely in kelp. Of course that was the island price. Multiples of this could be obtained in the southern markets. For those labouring on the shore, the cost price they received barely shifted. Only their number increased. Even this was retrospectively resented by the 8th Duke of Argyll, who complained that tenants wanted to substitute payments in kelp for rents paid by barley, rather than allow their enhancement. Thus this resourcefulness on the part of islanders was cast as an ‘unnatural lowering of rent’ from a ‘gratuitous benefit’. As the Highland lairds’ spending peaked, their tenants were paying through a means that, according to the 8th Duke, lacked proper ‘exertion’.

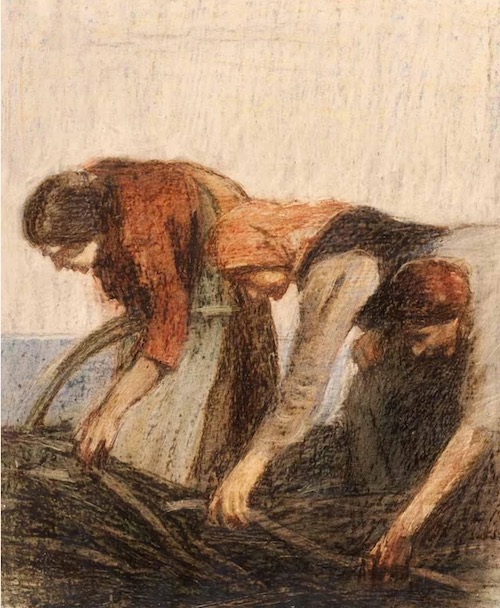

Kelp was made from four plants of the genus fucus: sea wrack, bell wrack, ware, and tangle. Although storms could throw them up on the shore, they commonly rooted on submerged rocks, exposed as the tide ebbed. Even at the lowest ebb tangle could be rooted in another 4 to 8 feet of water. ‘It requires the full strength of a man to pull up one of these plants from the bottom.’ The harvesting of ware and making of kelp was a summer activity, after potatoes went in, but could proceed alongside work on the grain crop with a supply of labour from cottar families. Wrack was cut from the rocks with hooks and sickles and had to be carried on the back to carts or drying-places further up the shore. Access to this ware was shaped by the tides, and if the low ebb fell at midnight then the families would rise and work to draw out the right plants as the waves washed over them. Sometimes ‘the night was so dark that if I did not see it I could feel it.’

Travelling in Kerry in 1844, Asanath Nicholson encountered sixty women making great sport at the shore collecting ware after a stormy night, who told her they might have to work ‘sometimes not fawrty days’ at it. But generally the work was considered hard. Máirtín Ó Cadhain gave a vivid portrait of a woman at work in Connemara in his short story An Taoille Tuile (‘The flood tide’): long exhausting hours in the water, prone to slips of foot and blade, sharp rocks, salt stinging in wounds, the weight of the ware and growing cold. The acute rheumatism to which kelpers were prone was remembered long after. The traveller James Hall would state in his 1807 Travels in Scotland that compared with the kelpers ‘the state of our negroes is paradise.’ Hall, however, had never been to America.

The kelp was then made in stone-lined pits above the beach, the length of one or two people and just over two feet wide. Sheltered from the wind by green turf, the seaweed was melted by a fire of peat or coal, turned and pressed into the hot stones with an iron rod called a ‘clatt’ until ‘it is found to be hard, solid, and resembling good indigo’. Like so much early industrial work, making a good product was an art learned by sharp eyes, practiced hands, and tested on the tongue. As far as possible stones and sand were to be kept out of the finished product – adulteration being a constant complaint of buyers.

And without doubt, the life of crofting and kelping could be attractive in the circumstances. Balemartine soon filled up and continued to draw migrants long after 1800. Dòmhnall Caimbeul of Balinoe may have been the son of the solid tenant farmer Donnchadh – grandson of Muireach – but in a crowd of eight children, many among them boys, as an elder son he would not inherit (this usually went to a younger son who was still on the farm when the parents retired). The opportunity of a decent croft and the promise of varied income was a good bet- necessarily varied, as the crofts were too small for subsistence. But as the crofts filled, a swelling population could only live as cottars, tenants at will or squatters on the already small crofts. This would be the fate of his son Seàrlas (or possibly Teàrlach), born in 1830.

Like the tide, markets turn. Dòmhnall had arrived in Balemartine just as the market for kelp faced obliteration.

As early as 1811 a glutted alkali market saw prices begin to fall. After the war, Britain began its march towards free trade and ever swifter technological innovation. The price was down to just above £9 by 1823, and despite a rearguard action by the Highland proprietors, barilla duties were drastically reduced in the early 1820s and the salt tax, which had discouraged the manufacture of artificial soda, abolished in 1825. That year a ton of kelp sold for £7. Barilla was, however, predominantly used by London soapmakers, and in the war years they had been overhauled by the Liverpool industry, which used kelp. Cheaper barilla made an alternative to kelp desirable to the Liverpudlians if they were to remain competitive, and it turned out that this was the moment for the keen entrepreneurial eye – or sheer good luck – of James Muspratt, a Dublin chemical manufacturer who had moved to Liverpool in 1822. He rapidly ramped up the Leblanc soda-making process, already known for three decades, to, as we would say, an industrial scale. This is one of the least explored, but most significant aspects of the Industrial Revolution, as the chemical industry turned away from organic materials to artifical manufactures generated by science. By 1827 the previous year’s store of kelp lay unwanted in Liverpool’s warehouses. Prices tumbled to £3 13s per ton by 1828. In 1840, the minister of Tiree looked wistfully back to the age of kelp:

As early as 1811 a glutted alkali market saw prices begin to fall. After the war, Britain began its march towards free trade and ever swifter technological innovation. The price was down to just above £9 by 1823, and despite a rearguard action by the Highland proprietors, barilla duties were drastically reduced in the early 1820s and the salt tax, which had discouraged the manufacture of artificial soda, abolished in 1825. That year a ton of kelp sold for £7. Barilla was, however, predominantly used by London soapmakers, and in the war years they had been overhauled by the Liverpool industry, which used kelp. Cheaper barilla made an alternative to kelp desirable to the Liverpudlians if they were to remain competitive, and it turned out that this was the moment for the keen entrepreneurial eye – or sheer good luck – of James Muspratt, a Dublin chemical manufacturer who had moved to Liverpool in 1822. He rapidly ramped up the Leblanc soda-making process, already known for three decades, to, as we would say, an industrial scale. This is one of the least explored, but most significant aspects of the Industrial Revolution, as the chemical industry turned away from organic materials to artifical manufactures generated by science. By 1827 the previous year’s store of kelp lay unwanted in Liverpool’s warehouses. Prices tumbled to £3 13s per ton by 1828. In 1840, the minister of Tiree looked wistfully back to the age of kelp:

At one time, about 500 tons of it were made in Tiree, which employed at least one-half of the adult population during the season... since 1837 none has been made.

In one short decade not only was the boom past, but the entire industry, the foundation of the crofting economy was vanished. But the people lived there still.

| « The Colony | The Famine » |