The Sea

In his instructions for his Chamberlain of 1771, the 5th Duke commented, ‘the island is over-peopled, and my farms oppress’d with a numerous set of indigent tenants & cotters... I will give them encouragement to settle in a fishing village.’ It took a century for something of this vision to be realised: a reorientation of the island from being Tir an Eorna, the land of barley, first to the shoreline, and eventually out to sea. The fish were always there, more or less. Islanders could see the boats of east-coast mariners hauling in from the nearby waters. Resources, however, are made of materials, in the minds of men and women, and with means. Without all of these they remain just fish in the sea.

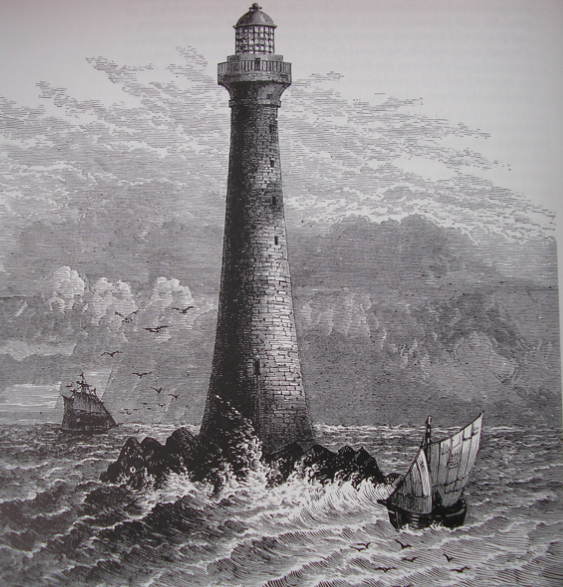

And what a sea. The mighty Skerryvore lighthouse was raised on a rock twelve miles south-west of Tiree between 1838 and 1844, in the centre of the area’s best fishing grounds. In the 1880s it recorded an average of 54 storms a year, ‘frightful tumults’ enduring a length of time equivalent to four hours for every single day of the decade.

And what a sea. The mighty Skerryvore lighthouse was raised on a rock twelve miles south-west of Tiree between 1838 and 1844, in the centre of the area’s best fishing grounds. In the 1880s it recorded an average of 54 storms a year, ‘frightful tumults’ enduring a length of time equivalent to four hours for every single day of the decade.

At first the Duke attempted to settle and employ supernumeraries in fishing villages, encouraged by some Kintyre fishermen, most prominently at Scarinish in the east of the island which today boasts its only harbour and the essential port for the Caledonian MacBrayne ferry from Oban. But with the American wars the young men preferred to try their luck in the army or navy. The venture failed commercially, but not for lack of potential. There were cod and ling that would be caught from long lines let out from the small boats, the mainstay of the island’s fishing. There were skate, eels, and for those of steady aim, sailfish to be harpooned for oil. Herring came to the bays, but catching these needed nets that the island lacked. More rarely, there was gurnard or turbot to be had, and for resources easier to hand, the poor were in the habit of snaring or collecting lobsters, crabs, cockles, limpets and razorfish, especially in times of scarcity. Yet only a couple of vessels persisted, despite offers of prizes for the largest hauls.

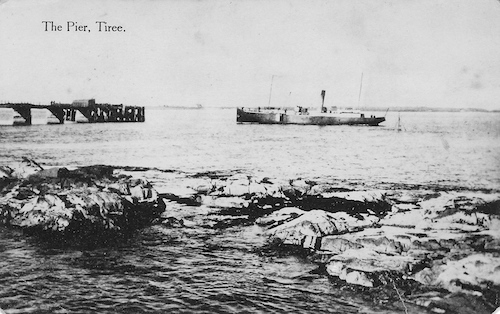

The reasons the men of Tiriodh stayed off the waters were similar to those that discouraged ‘improvement’ on land. Lines, nets, salt for curing and boats were a considerable investment that woud lie idle for much of the year. They were far from markets and could not compete with larger boats that came from the ports of the east coast. Lack of suitable harbours put any investment at risk, while those with farms or crofts often had to attend daily to agricultural tasks in fair weather, when the best fishing grounds were twelve miles or more distant. And of course until the 1820s, there was the lure of kelping.

So the people of Tiriodh had their boatbuilder in Scarinish from 1802, and their skiffs, numbering 94 in 1837 and allegedly 70 boats in the cod and ling fishery in 1851. In reality only around a dozen were really active in these years, and aside from two large households of fishermen lured from Aberdeen, sheer lack of alternatives probably drove what engagement there was. ‘Though almost all are occasional fishers, yet few follow it steadily as a profession’, it was noted. In 1851, half of the island’s 49 fishermen recorded in the census were also agricultural labourers. But a decade later there were 109 fishermen in 83 households, 146 by 1871, and 175 in 1881, now a substantial part of the island’s male workforce. A combination of new market access, and a desire to stay on an island with few alternatives, had turned men towards the waves.

These men sailed out among the Aberdeen boats that came in large numbers for the ling. As with everything, the sea had its season. From the end of November until March there was no fishing and the whole island was under the lock and key of the storms. Boats were typically crewed by five (so households combined) and fished with long lines baited by sand eels and shellfish on up to a thousand hooks. The patient work of collecting and attaching the bait by a horsehair was typically done by women. The boats were open wooden skiffs, sixteen to twenty-six feet long, lathered with Archangel tar known as an tear buidhe, the yellow tar. The simple sail was designed so that it could quickly be hauled down in a squall. The boats could be no bigger because there was nowhere to keep them, and they risked being smashed if left to ride at anchor or left on the shore. For the most part fishing became the resort of cottars, and they struggled to get by without the indulgence of neighbouring crofters for the grazing of a cow or a potato patch. In 1883, the island’s doctor commented on the fishermen’s children being ‘in want of milk a good deal’. ‘And I suppose that would tell in the future?’ ‘Of course.’

It was inevitably dangerous. Eachann Dòmhnallach, a spokesman for the Balemartine cottars, recalled losing his brother to the sea; the island remembers still the disaster of 8th July 1856 when a little flotilla from Balephuil were caught by a storm off Skerryvore and nine men lost. Getting a boat ashore in a high sea was no mean feat. The ballast of stones was shifted astern to keep the rudder down and prevent it leaving the water and the vessel being cast sideways. The skipper sees a break in the waves and shouts for oarsmen to heave forward. As the prow hits the beach the bowman is ashore in a moment, joined by people on the shore to haul it up as the rest of the crew leap out to push from the stern. When all is safe, the catch passes to the women to be processed.

In his apologia of 1883, the 8th Duke noted the enduring ‘very large population of mere cottars, some of whom live by fishing... in the language of geology... the detritus of the old subdivided crofters and sub-tenants.’ This was indeed the fate of Seàrlas Caimbeul, who left his parents Dòmhnall and Mairead’s croft in Balemartine when he married Muireall, daughter of the shoemakers Uisdean and Ciorstaidh, in 1854. Typically, his much younger brother Seamas would inherit when farmwork became too much for his parents. In reality Seàrlas was probably providing labour on the now substantial croft into the 1860s, as his still resident teenage brother tried his hand at fishing. By 1871 Seàrlas had seven children and the two brothers, both now married, ventured as grocers to make ends meet. But crucially the land was Seamas’s. By 1881 Seàrlas, now over fifty years of age and superfluous to requirements on land, was braving the waves to fish with his son Dòmhnall.

In his apologia of 1883, the 8th Duke noted the enduring ‘very large population of mere cottars, some of whom live by fishing... in the language of geology... the detritus of the old subdivided crofters and sub-tenants.’ This was indeed the fate of Seàrlas Caimbeul, who left his parents Dòmhnall and Mairead’s croft in Balemartine when he married Muireall, daughter of the shoemakers Uisdean and Ciorstaidh, in 1854. Typically, his much younger brother Seamas would inherit when farmwork became too much for his parents. In reality Seàrlas was probably providing labour on the now substantial croft into the 1860s, as his still resident teenage brother tried his hand at fishing. By 1871 Seàrlas had seven children and the two brothers, both now married, ventured as grocers to make ends meet. But crucially the land was Seamas’s. By 1881 Seàrlas, now over fifty years of age and superfluous to requirements on land, was braving the waves to fish with his son Dòmhnall.

The censuses however tell another story about Tiriodh and the sea. By the 1860s there were regular steam services to nearby ports and on to Glasgow (Glaschù). Several dozen islandmen now worked as seamen, ship’s porters and ships’s carpenters. After all, this was a crucial means to get fish to wider markets as, at last, workers’ incomes in Victorian Britain began to rise. Yet this crucial connectivity to markets which could keep the cottar population’s heads above water – most of the time – though fishing was also a gateway to innumerable new options around the world. The sea became a reason to go as much as to stay. When Eachann Dòmhnallach was asked about the young men of the island by a member of the Napier Commission on the condition of crofters in 1883, he replied, Yes, there are many of them away; some at the east coast fishing, some on board steamers, and some in all quarters of the earth'.

| « The Famine | Exodus » |