Exodus

At the beginning of the 1770s, it was remarked that, ‘The inhabitants of Tiry have been immemorially strangers to emigration. They are… naturally so much attached to their homes that many have arrived at a very old age without the smallest acquaintance with farms and neighbours at the distance of only eight miles from them.’ This was, of course, an exaggeration. Tiriodh was already sacrificing its share of young men to Britain’s imperial wars; 120 by one account to America, 100 left to fight France in 1792. Indeed the census of 1841 found extraordinarily only 67 men for every 100 women aged in their 50s on Tiree – a legacy of the Napoleonic maelstrom?

At the beginning of the 1770s, it was remarked that, ‘The inhabitants of Tiry have been immemorially strangers to emigration. They are… naturally so much attached to their homes that many have arrived at a very old age without the smallest acquaintance with farms and neighbours at the distance of only eight miles from them.’ This was, of course, an exaggeration. Tiriodh was already sacrificing its share of young men to Britain’s imperial wars; 120 by one account to America, 100 left to fight France in 1792. Indeed the census of 1841 found extraordinarily only 67 men for every 100 women aged in their 50s on Tiree – a legacy of the Napoleonic maelstrom?

Simply pushing or luring people out of the island was one solution to its putative over-population, but one that the islanders were reluctant to entertain. Transatlantic emigration, the main option at the end of the eighteenth century, was an expensive business if one was not prepared to travel as an indentured servant (which had its own costs of long years of labour). This became all the more so when the Passenger Vessels Act of June 1803, following a panic about the potential scale of movement associated with the Clearances, was passed ostensibly to improve conditions in passage but just as much as a way of trebling the fare.

Then there was kelping, and potatoes; hard graft but a means to stay.

And, then, after 1825, there were only potatoes.

With Britain’s numerous wars, men had come and gone, and fallen never to return. In the 1820s, a radically different kind of movement began: seasonal labour to the harvest fields of lowland Scotland, to a whole different landscape and language. Where were your idle people now? And it was a movement dominated by young unmarried women. Tiree had always exported its black cattle, horses and pigs. Now it drew in scarce cash from the labour of its young folks’ hands over the sea. Soon hundreds made the trip each year, from a total population still under four thousand. This may be why, for example, none of Uisdean Ròs’s daughters appear in the census dwelling in Tiriodh in their teens. They brought back earnings, new tastes, new clothes, and sometimes, ‘infectious and dangerous disorders.’ Although this movement encompassed the majority of the island’s youth, it also came to draw in the poorer tenants, no less than a third of those paying under £5 in rent doing harvest or seasonal fishing away by 1845.

With Britain’s numerous wars, men had come and gone, and fallen never to return. In the 1820s, a radically different kind of movement began: seasonal labour to the harvest fields of lowland Scotland, to a whole different landscape and language. Where were your idle people now? And it was a movement dominated by young unmarried women. Tiree had always exported its black cattle, horses and pigs. Now it drew in scarce cash from the labour of its young folks’ hands over the sea. Soon hundreds made the trip each year, from a total population still under four thousand. This may be why, for example, none of Uisdean Ròs’s daughters appear in the census dwelling in Tiriodh in their teens. They brought back earnings, new tastes, new clothes, and sometimes, ‘infectious and dangerous disorders.’ Although this movement encompassed the majority of the island’s youth, it also came to draw in the poorer tenants, no less than a third of those paying under £5 in rent doing harvest or seasonal fishing away by 1845.

So to service those debts and dependencies from off the island – rent, coal, timber, peats (barely yet tea, coffee, or sugary goods) the people now needed to depart, temporarily, to obtain the wherewithall to do so.

The Duke, however, had greater ambitions. A minor industry now existed to draw off Britons to the rapidly expanding settler colonies in Canada and Australia. The agricultural products of these countries were a new organic resource frontier, pushing up demand for labour and for eager minds to manage . There can be no doubt that before the 8th Duke took on the direction of the Argyll lands in 1846, the estate’s policy was the systematic reduction of population by removal, to finally realise the dream of improved farms. This was not to be, in the Duke’s mind, at any cost (although its implementation might be a different matter). Already in 1845 a target had been set of lowering the population by 40%. But early successes had not rebounded well, the Chamberlain reported: people ‘had no wish whatever to emigrate... they have no hope of bettering their condition, as the accounts sent from those persons who have emigrated... give no encouragement to persons.’

The famine was to make that population simultaneously more vulnerable, and pliant. A first step was directly in the provision of relief. It was to be refused to those who could leave, at least seasonally, and granted only to ‘those who are so circumstanced they cannot do so.’ In May 1851 the Duke stated clearly: ‘I wish to send out those whom we would be obliged to feed if they stayed at home – to get rid of that class is the object.’ Whilst he may have acted with, in his mind, the best interests of his subjects at heart, there is no question that the goal of the 8th Duke’s regime was to systematically drive people from the island, albeit by technically legal means. It may be that the man charged with implementing this regime, Chamberlain John Campbell, insisted that he only served eviction notices ‘on the indolent, and bad characters, widows and young men whose fathers died and a few families... fitted to emigrate.’ He is a man remembered darkly as The Great Factor, Am Bàillidh Mòr, as Iain Dubh (‘Black John’) on Tiriodh and the Ross of Mull. In 1850 the limited kelp manufacture was deliberately delayed to encourage emigration. As historian Tom Devine has pointed out, the fact that any of the hundreds who signed up to leave in these years might consider delay for the purpose of the bleak remuneration to be had for kelp in 1850 is a sign of how reluctantly they departed. Campbell confiscated cattle stocks for rent arrears, eroding the viability of tenancies, and in the 1860s the 8th Duke ventured on the expedient of appointing a Factor who could not speak Gaelic to frustrate attempts at intermediation and make people more likely to leave. These local strategies of management were doubtless much more important in encouraging emigration than the more famous efforts of the Highland and Island Emigration Society that was set up with the support of Trevelyan and Sir John McNeill between 1851 and 1856.

In 1841 the population of the parish of Tiriodh and Coll (its less populated neighbour immediately to the north-east) nearly touched 6 000, with many seasonal workers abroad. By 1881 it was 3 375. Even though some of the extreme losses by 1849 were temporary as the able-bodied and workless left the famished island, still some 1 354 emigrated between 1847 and 1853. And although net migration had not been trivial before the 1840s, it was always offset by growth. Thereafter it was an unstemmable haemorrhage. 12% in the 1850s, 19% in the 1860s, 11% in the 1870s, 17% in the 1880s. And even for those who remained, especially the elderly, there were new dependencies on markets and remittances: ‘we have to buy all our meal from Glasgow. Our sons and daughters gather our rent through the world.’

What choices were there for Caitrìona Caimbeul? She was 15 in 1880. Although her uncle held a croft, her own family were cottars and her fifty-year-old father Seàrlas put out to sea in the fishing season with her elder brother Dòmhnall. Her mother and her aunts had doubtless taken the high road to the lowlands for temporary earnings. Like so many of her generation, she would go too. And not return to the place, where a couple of years later a Tiriodh crofter would proclaim, ‘We live in that part of Scotland where... suffering is taking place, and oppression and slavery.’ The language was coloured by the contemporaneous Irish Land War and the context of legal and physical battles over land rights in the Hebrides of the 1880s. But there was bitterness there, and a deep sense of constraint.

And so on census night 1881, Caitrìona Caimbeul of Tiriodh found herself a servant to the Alexanders, a family of Margaret, a pensioner, and her warehouseman son David and seventeen-year old daughter Anna who was still at her schooling in Clarement Street, a row of smart stone-faced tenements to the west of Glaschù’s centre. The building is now gone; today it is, fittingly, the site of the Sgoil Gàidhlig Glaschu, the city’s Gaelic-language school. Caitrìona felt emboldened now to elevate herself for the record to the age of her fellow resident and mistress, at 17. In truth she was still two years younger. Fortune would smile on her, for a time. Where was it that she encountered Maol-Chalùim Darroch of Jura – like so many of his wandering age in the Islands, a merchant seaman? They could talk the Gaelic together, and always did throughout their married life as they wandered between apartments in various towns, him rising through the ranks. But they were always anchored to his home place in Jura. Still, it must have given some satisfaction to have been living in a grand apartment on Glasgow’s Argyle Street for a time around 1910 – right around the corner from where she first entered service thirty years before. Perhaps some of this grandeur rubbed back onto her father Seàrlas, who declared himself, with a nod back to his brief stint as a grocer, a ‘retired merchant’ in the census of 1901. Or perhaps with less good humour he wished to forget the fishing he had struggled on with into his sixties, and that had as a young man invalided Dòmhnall, his son.

And so on census night 1881, Caitrìona Caimbeul of Tiriodh found herself a servant to the Alexanders, a family of Margaret, a pensioner, and her warehouseman son David and seventeen-year old daughter Anna who was still at her schooling in Clarement Street, a row of smart stone-faced tenements to the west of Glaschù’s centre. The building is now gone; today it is, fittingly, the site of the Sgoil Gàidhlig Glaschu, the city’s Gaelic-language school. Caitrìona felt emboldened now to elevate herself for the record to the age of her fellow resident and mistress, at 17. In truth she was still two years younger. Fortune would smile on her, for a time. Where was it that she encountered Maol-Chalùim Darroch of Jura – like so many of his wandering age in the Islands, a merchant seaman? They could talk the Gaelic together, and always did throughout their married life as they wandered between apartments in various towns, him rising through the ranks. But they were always anchored to his home place in Jura. Still, it must have given some satisfaction to have been living in a grand apartment on Glasgow’s Argyle Street for a time around 1910 – right around the corner from where she first entered service thirty years before. Perhaps some of this grandeur rubbed back onto her father Seàrlas, who declared himself, with a nod back to his brief stint as a grocer, a ‘retired merchant’ in the census of 1901. Or perhaps with less good humour he wished to forget the fishing he had struggled on with into his sixties, and that had as a young man invalided Dòmhnall, his son.

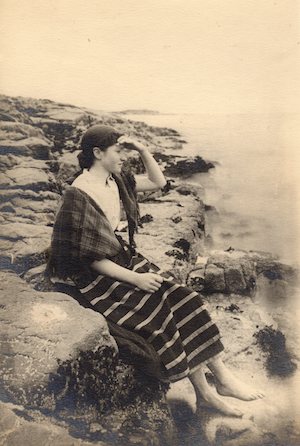

So from the Caimbeul colonist Dòmhnall at the beginning of the eighteenth century, the line had passed down through two generations of farmers, to a crofter, to a labourer and fisherman, to Caitrìona’s life: on the beach at Balemartine, baiting the fishhooks and waiting for the boats’ return, then departure, then service – and then a Glasgow apartment and wife to a sea captain. She, at least, might have assented to the island physician’s view of the great exodus expressed before the Napier Commission in 1883: ‘Their condition is that they would not return, although they would get their land back again for nothing.’

| « The Sea | An Iodhlann » |