The Colony

Until 1674, Tiriodh was the land of MacIllEathain. That year the old lords forfeited their lands through debt to the mighty Campbells, Earls of Argyll. Highland lords had traditionally governed through allotting lands to ‘tacksmen’ who collected rents in kind and coin, demanded labour services from the tenants, and levied soldiers when required. Tenants and sub-tenants understood these relationships, although often harsh, to be part of a world of mutual support, rather than the exercise of contractual rights to freehold property and judicial authority. Until 1748 all but the most serious of crimes were tried by the landlord and his agents.

Until 1674, Tiriodh was the land of MacIllEathain. That year the old lords forfeited their lands through debt to the mighty Campbells, Earls of Argyll. Highland lords had traditionally governed through allotting lands to ‘tacksmen’ who collected rents in kind and coin, demanded labour services from the tenants, and levied soldiers when required. Tenants and sub-tenants understood these relationships, although often harsh, to be part of a world of mutual support, rather than the exercise of contractual rights to freehold property and judicial authority. Until 1748 all but the most serious of crimes were tried by the landlord and his agents.

The MacIllEathain powers of the tacksmen and their followers were extirpated. From the 1690s, Caimbeulls were settled in their place. At the same time that thousands of Scots were crossing the North Channel to make a new life in plantation Ulster, Tiree became a colony. Is this too strong a word? Tiree’s leading historian, Eric Cregeen, thought not: ‘The new population... lived as loyal, privileged and envied colonists amidst the dispossessed clans.’ They constituted a little thirty-mile-square corner of Argyll’s overall empire, one hundred times the size of Tiree. Not that the head tacksman actually resided on the island, but that clan’s members came to tenant most of the island’s thirty-or-so farms, in turn sub-letting them to other families. By the 1720s, the now Duke of Argyll was living far to the south in Oxfordshire, anxious as a great British magnate to stay close to the centres of power and patronage around Parliament and Court after the Act of Union in 1707. Instructions and accounts flew back and forth between the duke and his officials, the chamberlain and factors who ran his estate – all of course in the Beurla (English).

Being a magnate was an expensive business. One not easily covered by the rental income forwarded by tacksmen, itself largely earned through the cattle trade; and to which rents in kind contributed nothing. It is not surprising that the dukes became great advocates for improvement, for hauling their indolent subjects into the future to produce what we might call a ‘marketable surplus’. Historians can be grateful for the remarkable surveys and censuses taken in the 1760s and 1770s to assess the island’s potential. But where were the markets on Tiree? And indeed what kind of commerce and competition could exist when one man ruled over every tenancy, enforced the laws, and possessed the only serious purchasing power on the island? When he refused to relinquish control over a population severed from any traditional ties of sympathy or language?

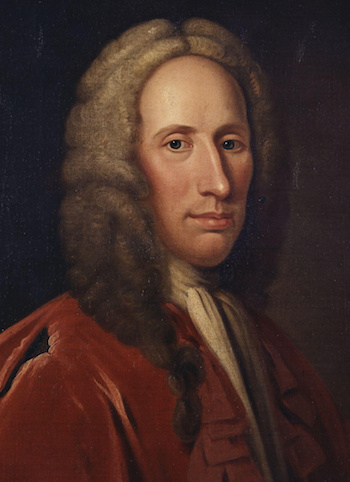

So do the best laid plans go awry. In 1736 Argyll decided to shake up the old system of tacksmen and introduce modern property rights and farming. He sent no less a personage than Duncan Forbes, senior legal officer of Scotland and Whig MP (and with no Gaelic), to abolish the tack-system and establish new farms rented at market value. Forbes’ party travelled well-fortified with rhubarb and gum pills for health, several gallons of whiskey and fourteen dozen bottles of wine. But their new order did not survive the bitter winters and cattle plagues of the 1740s as tenants fell massively into arrears. Repeated efforts to establish large farms on much longer leases, introduce lowland agricultural techniques, and foster local linen and fishing industries foundered. Exposed to highly variable yields and uncertain markets for their cattle, and to years of harsh rents and tenurial uncertainty, islanders lacked the goods to stock such farms. It is notable too that activities taking place in farms and cottages, such spinning and weaving, were treated by the landlord as a potential adjunct to the rental value despite the fact they bore no obvous connection to his rights in the land.

So do the best laid plans go awry. In 1736 Argyll decided to shake up the old system of tacksmen and introduce modern property rights and farming. He sent no less a personage than Duncan Forbes, senior legal officer of Scotland and Whig MP (and with no Gaelic), to abolish the tack-system and establish new farms rented at market value. Forbes’ party travelled well-fortified with rhubarb and gum pills for health, several gallons of whiskey and fourteen dozen bottles of wine. But their new order did not survive the bitter winters and cattle plagues of the 1740s as tenants fell massively into arrears. Repeated efforts to establish large farms on much longer leases, introduce lowland agricultural techniques, and foster local linen and fishing industries foundered. Exposed to highly variable yields and uncertain markets for their cattle, and to years of harsh rents and tenurial uncertainty, islanders lacked the goods to stock such farms. It is notable too that activities taking place in farms and cottages, such spinning and weaving, were treated by the landlord as a potential adjunct to the rental value despite the fact they bore no obvous connection to his rights in the land.

For the wealthier tacksmen, the splitting of holdings among sub-tenants was an easier way to keep rents buoyant. Most of the farms followed runrig, a system by which the land was communally grazed and then split regularly among a group of tenants by lot ensuring they were not stuck with perennially difficult ground. In a land of few boundaries and short, intense bursts of agricultural activity the drive for larger, separated farms was not a mere economic reform but an attack on the forms of shared work and sociability by which islanders came to know and feel their community. And then there was politics. The islanders’ Jacobite instincts were kept in abeyance by economic power, and by bursts of coercion, with weapons seized and properties burned after the rebellions.

Yet over time, the absolute divides of the colony were not maintained. MacIllEathains crept back. By 1776 three of the seven Tacksmen had that name. If the name Caimbeul still predominated at the very top of the (largely absentee) hierarchy, it was as equally prevalent among the cotters, fishermen, and herdsfolk of the island as the slightly wealthier tenant farmers. They were no longer an incoming caste. Muireach Caimbeul, who would have sat listening to the sermon as Beurla in the 1760s, was possibly a son of an original colonist, Dòmhnall Caimbeul, who rented the farm of Balinoe that later fell to Muireach. Yet by that decade his second wife would be a MacIllEathain. Among the mass of islanders, the fundamental divide had become one not between clans, but between them and the distant landlord, his factor and a handful of wealthier landholders: the dozen descendants of the tacksmen who held over half the island between them yet paid substantially less rent than the land shared among the other 155 tenants.

Even in these circumstances, the islanders did not lack for innovation. Barley was long turned into whiskey to provide a marketable good beyond the small numbers of cattle that left the island. Indeed the leftovers of the still made good cattle feed and the activity fitted well with an annual calendar of intense bursts of work punctuated by quiet and weather-beaten periods. In 1786 the government effectively outlawed the ubiquitous farm still, introducing new duties and a rapidly rising license fee. This was both a burden and an opportunity for Tiriodh, for the now illegal island distillers produced a better product more cheaply than the capitalised licit trade, a product in high demand in the south. Barley transmogrified into uisge beatha paid the rents. Yet the 5th Duke was determined to bring it under his control. In 1801 no fewer than 157 were prosecuted for illegal distilling, a twentieth of the island’s population. There were to be exemplary evictions of a tenth of these, and as the landlord controlled every inch of the island, this was tantamount to expulsion. The barley was to be used to pay rents directy instead. All distilling would be done by the landlord’s own business.

Decades later the 8th Duke, in the middle of the ‘Land War’ of the 1880s, would pompously proclaim that , 'every single step towards improvement which has been taken during the last 130 years, has been taken by the proprietor and not by the people.... [among them] the very desire of better things is absent'. It is certainly true that the proprietor, and the political economy of the nation, determined in the end the possibilities of betterment for the inhabitants of Tiriodh. The dukes also continued to believe that the rights of property extended to restraining certain classes of islander from traditional pleasures, refusing to allow them an inn. And after locals helped themselves to drink washed ashore from the foundered vessel Cairnsmore in 1885, the lord banned the consumption of alcohol among those with rentals under £30 on pain of eviction.

Decades later the 8th Duke, in the middle of the ‘Land War’ of the 1880s, would pompously proclaim that , 'every single step towards improvement which has been taken during the last 130 years, has been taken by the proprietor and not by the people.... [among them] the very desire of better things is absent'. It is certainly true that the proprietor, and the political economy of the nation, determined in the end the possibilities of betterment for the inhabitants of Tiriodh. The dukes also continued to believe that the rights of property extended to restraining certain classes of islander from traditional pleasures, refusing to allow them an inn. And after locals helped themselves to drink washed ashore from the foundered vessel Cairnsmore in 1885, the lord banned the consumption of alcohol among those with rentals under £30 on pain of eviction.

Across the whole of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, lordship over Tiree entailed bringing superior judgement and moral sensibility to bear on the islanders, with ‘their natural propensity to laziness and idleness.’ And of course, the dukes felt themselves to have worked hard for change - according to the standards of work with which they were familiar – and with the best of intentions. For the 8th Duke, who presided over Tiree from the 1840s until the end of the century and served as Secretary of State for India under Gladstone’s premiership, all those improvements which came to Tiree were seen as a trickledown of knowledge and industry from greater exemplars; an ethos, it should be noted, that also lay behind his zeal for reforming and expanding access to education nationally. The island and the minds of the islanders were like a tabula rasa. His enhanced rental roll after decades of eviction and reform, he wrote in 1883, was ‘more like the increase of value which arises on the discovery of a new country. It may be said to represent the first advent of civilization in the settlement of a new land.’

| « Tiree | Kelp » |