An Iodhlann

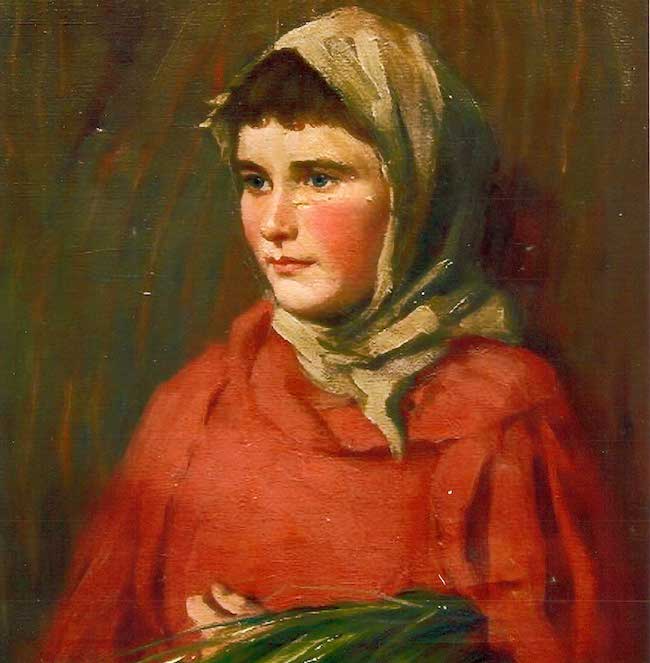

The people of Tiriodh have always been telling each other, and any others who cared to listen, their own histories. In the nineteenth century its small population even contained a number of poets whose versifying has been preserved, the bards of Tiree (Na bàird Thirisdeach). It is telling, no doubt, that one of the most famous and moving of these works, by Iain MacIllEathain of Baile Mhàrtainn (Balemartine) is called, ‘Manitoba’, and was written on the occasion of some of his relatives departing the island in 1878.

‘S e faileas na daoine: ‘s nach sgarach an saoghal

‘S e ‘s fasan dha daonnan bhith caochladh gach là.

The people are mere shadows; how fickle the world is!

It is ever its nature to change day by day1.

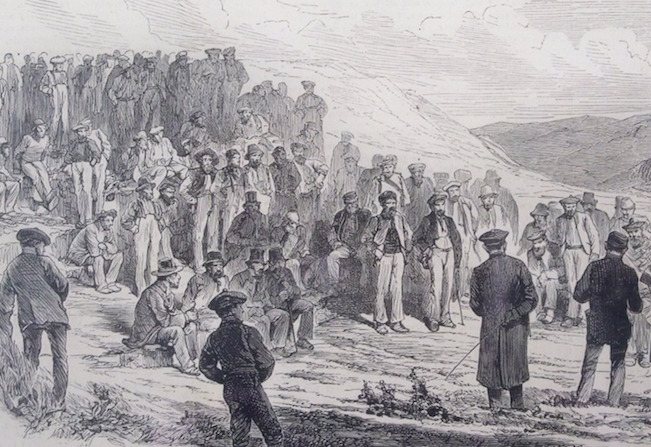

Literary output, also passed down by mouth in gatherings in the island’s low-slung stone houses, was particularly intense around the years of the ‘Land War’ of the 1880s. Partly taking their cue from events in Ireland, crofters and cottars across the Hebrides protested their circumstances, leading on Tiriodh to the seizing of a farm in the summer 1886 by men claiming it should have been divided and offered out to the poor as crofts. Police sent to the island to enforce a wave of ejectments by the landord were repulsed, and in a somewhat febrile atmosphere, the government sent two naval vessels with 250 troops to restore order. ‘There is war in Tiree!’ proclaimed The Times of 24th July 1886. In the event, the troops were received amiably, several islanders spent some months in gaol, but the following year an investigating commission reduced rents and cancelled arrears. A generation later, in the 1910s and early 1920s, long years of campaigning led to most of the island’s farms being broken up into crofts.

But by that time there were only 1 800 people living on the island. A century later, in the census of 2011, only 653 people remained, and under half of them habitually used the Gaelic. Tiree has become a centre for surfing, and a much-loved holiday destination, not least among the many with ancestral ties to the place, now living in Glasgow or all the Manitobas of the world and far outnumbering those who remained. New enterprises on the island seek to market improbably Hebridean products such as tea and gin. Tiree now sustains fewer people than for perhaps four hundred years or more. There is little sign of the exodus abating.

It was in 1883, amid the Land War, that the 8th Duke of Argyll wrote his apologia for his family’s governance of Tiree. He had always perceived himself well received there, and undoubtedly was personally hurt by the events. He viewed Tiree’s often difficult history as a process of modernization guided solely by the foresight and hands of the proprietors, one that eventually secured a viable living for its inhabitants. That was the way of the world, and a way for best, despite the views of those who succumbed to the ‘Hibernian influence’ that had prompted the ‘detritus’ of the place into the ‘exercise [of] terrorism.’ And perhaps, as the connectivity of the twenty-first century at least allows emigration without those people becoming mere shadows in memory and verse, it remains the way of the world.

Some bards perceived the story differently. In 1872, the much-loathed (but also much-loved, by his family) Iain Dubh Caimbeul, the ‘Great Factor’ of the island, died. He had presided over the famine and its bitter aftermath. An excoriating poem was written as a mocking eulogy, a ‘Lament for the Great Factor’, declaring how Gum bi a’ Factor air thoiseach san t-sloc sa bheil Sàtan (‘The Factor will be pre-eminent in Satan’s pit’), and how fires were lit and the whiskey drunk in celebration from the Hebrides to Canada. This poem was collected and recorded a century later by Eric Cregeen from an informant on the Ross of Mull, the story being that it was composed there spontaneously by one Uisdean Ròs, an old man once evicted by ‘Black John’, on hearing of the Factor’s death. Yet the Scottish censuses record no such person dwelling in Mull in the 1870s or the immediately previous decades. In fact, there was only one Uisdean Ròs of the right age in the whole of Scotland to match this tale, who did indeed come from the Ross of Mull, but had moved to Tiriodh, married Ciorstaidh Dòmhnallach and perhaps tellingly lived among the bards of Baile Mhàirtinn: my great-great-great grandfather. There’s no further evidence of this, of course, but it’s tempting to think I am not the first in the family to have contributed to writing the history of Tiree – as well as taking the odd drop of whiskey.

Old ways die hard but live differently. In 1995, a new way appeared to record and visualise the history of the world of Tiree (and there surely can be few places in the world now that Tiree has not touched?): An Iodhlann. Named after the old stack-yards where the islanders’ harvests would be stored, An Iodhlann is Tiree’s historical centre, a small museum, and – in 2020 above all else - a digitized collection of images and objects containing over 12 000 catalogued items, and ever-growing: 'old letters, emigrant lists, maps, reports, artefacts, photographs, stories and songs'. They might be a 1910s comic book or 1920s mail-order catalogues, family and school photographs, records of the ancient monuments and gravestones of the island, newspaper clippings of native children risen to fame or notoriety overseas. A dozen volunteers staff the work, enthusiastically guided since its inception by John Holliday, an incomer himself and previously the island’s doctor. Their ongoing labour complements the intensive oral histories of the island taken in the twentieth century and made available by Tobar an Dulchais (‘the well of the homeplace’). Most of the island’s older records, compiled by the powers-that-were, lie of course elsewhere in Inveraray (the seat of the Dukes of Argyll, where major work is being undertaken on digitization) or Edinburgh.

Old ways die hard but live differently. In 1995, a new way appeared to record and visualise the history of the world of Tiree (and there surely can be few places in the world now that Tiree has not touched?): An Iodhlann. Named after the old stack-yards where the islanders’ harvests would be stored, An Iodhlann is Tiree’s historical centre, a small museum, and – in 2020 above all else - a digitized collection of images and objects containing over 12 000 catalogued items, and ever-growing: 'old letters, emigrant lists, maps, reports, artefacts, photographs, stories and songs'. They might be a 1910s comic book or 1920s mail-order catalogues, family and school photographs, records of the ancient monuments and gravestones of the island, newspaper clippings of native children risen to fame or notoriety overseas. A dozen volunteers staff the work, enthusiastically guided since its inception by John Holliday, an incomer himself and previously the island’s doctor. Their ongoing labour complements the intensive oral histories of the island taken in the twentieth century and made available by Tobar an Dulchais (‘the well of the homeplace’). Most of the island’s older records, compiled by the powers-that-were, lie of course elsewhere in Inveraray (the seat of the Dukes of Argyll, where major work is being undertaken on digitization) or Edinburgh.

Through An Iodhlann ‘the island, its people and the wider diaspora’ now curate their own history. They forge and re-found connections, bringing their harvest in, entry by entry, to the stack-yard. There may be no oats grown on Tiree any more; those are mostly sown elsewhere, some perhaps amid the wheat, canola and more familiar flaxseed of Manitoba. The population has dwindled; the economy is unrecognizable; outsiders hail the old tongue rather than disparage it. Enduring is not easy. Yet history, and the need to be part of something, flourishes. Connections may be more Facebook than face-to-face, but the meandering, serendipitous deposit of images or ever-furcating family trees gives that history an organic, rhizomatic quality that does not ossify into the mere persistence of a few cultural clichés on the mantelpiece. The objects are too many, each entry gifting that strange surprise with which we recall the once familiar; and each with its manifold stories.

Through An Iodhlann ‘the island, its people and the wider diaspora’ now curate their own history. They forge and re-found connections, bringing their harvest in, entry by entry, to the stack-yard. There may be no oats grown on Tiree any more; those are mostly sown elsewhere, some perhaps amid the wheat, canola and more familiar flaxseed of Manitoba. The population has dwindled; the economy is unrecognizable; outsiders hail the old tongue rather than disparage it. Enduring is not easy. Yet history, and the need to be part of something, flourishes. Connections may be more Facebook than face-to-face, but the meandering, serendipitous deposit of images or ever-furcating family trees gives that history an organic, rhizomatic quality that does not ossify into the mere persistence of a few cultural clichés on the mantelpiece. The objects are too many, each entry gifting that strange surprise with which we recall the once familiar; and each with its manifold stories.

Of course, it’s still so much history in absentia. But isn’t that a condition of history? An Iodhlann surely matters by far the most to the six hundred-odd people on the island, but also to a host of others who left, or whose ancestors left, for better lives. For these people, there is no desire to go back to some imagined hard (or romantic) past. But there is a curiosity – a respect – for a might-have-been. For what was lost as well as gained.

This is not a question of weighing. There is no final accounting of gain or loss to be made here. There are, instead, feelings that might be ambiguous, or contradictory. That is also a condition of history. We go to the stack-yard not only to find the ways that we are, or our ancestors were, ‘of a place’, but all the more to discover what could have been and could still be in being. That is a search that we all share – the islander, the diaspora. Day by day, things change, and things are lost. There’s no avoiding this: how, at any point in its history, could Tiriodh have stayed the same? But that is not the same as saying that any particular loss is tolerable or inevitable. This is what an openness to history allows us to ponder, with feelings that can only be mixed. And so expanding our histories of might-have-beens is to enrich our own lives, and contributes to another form of enrichment, in helping to expand our sympathies towards others’ losses.

This is not a question of weighing. There is no final accounting of gain or loss to be made here. There are, instead, feelings that might be ambiguous, or contradictory. That is also a condition of history. We go to the stack-yard not only to find the ways that we are, or our ancestors were, ‘of a place’, but all the more to discover what could have been and could still be in being. That is a search that we all share – the islander, the diaspora. Day by day, things change, and things are lost. There’s no avoiding this: how, at any point in its history, could Tiriodh have stayed the same? But that is not the same as saying that any particular loss is tolerable or inevitable. This is what an openness to history allows us to ponder, with feelings that can only be mixed. And so expanding our histories of might-have-beens is to enrich our own lives, and contributes to another form of enrichment, in helping to expand our sympathies towards others’ losses.

So, one day I hope to go to Tiree. I will still be writing history in absentia, and in relative ignorance, but perhaps with sharpened sympathies. And maybe it will be better history. I already know well of course that I have a great deal of comfort that my ancestors did not. Yet there could always have been other comforts, and other sorrows. For every step differently travelled, more and other left-behinds. And that journey can also be a meditation on luck. It’s an idea not much loved by historians, and one that can hardly be thought without some ambiguity (‘what did I do to deserve?’), but in terms of our individual lives, history is still very much the embodiment of luck (or ill-luck). For we do not make the roads we walk down, and it is not always our choice whether we can walk them. Or as it was put by Eachann Dòmhnallach, spokesman for the cottars of Baile Mhàrtainn in 1883, when a member of the Napier Commission asked what land he and his compatriots had for their needs: ‘The high road’. ‘No land at all? – ‘Nothing whatever.’ ‘Not even a bit of ground for potatoes?’ – ‘Not the breadth of the soles of our feet.’

| « Exodus | Bibliography » |